by David J Bobb

Humility is often associated with weakness—not with strong leaders. In his new book, David J. Bobb Explains why that’s a mistake.

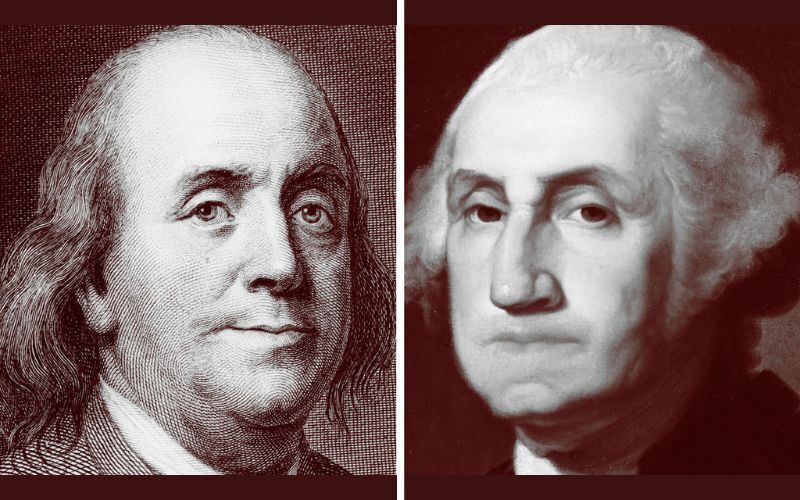

Before he became one of America’s ultimate success stories--inventor, scientist, diplomat, and the consummate connector of people and ideas--Benjamin Franklin was convinced that he was a moral mediocrity.

Disgruntled with the disorder of his life, frustrated by his lack of productivity, and bent upon becoming more frugal, Franklin set out on a project he called “moral perfection.” Having made a list of 12 areas of attitude and action that needed improvement, the 27-year-old Philadelphian asked a friend to look over his list.

What his friend told him had to hurt a little, for as Franklin wrote in his Autobiography,the man “kindly informed me that I was generally thought proud; that my pride showed itself frequently in conversation.” Humility had to be the 13th virtue in his project.

”Humility asks us to acknowledge our imperfections. It requires that we admit when we are wrong and then change course.”

Not many friends--let alone business colleagues--are quick to confront arrogance in those around them. And if you’re arrogant, you’re certainly not eager to admit it. “Humility is the first of the virtues,” Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. said, “for other people.”

Of all the virtues vital for successful leadership, humility elicits the most lip service--and the least decisive action. It’s a hard-won virtue, constantly demanding an honest assessment of one’s real merit. Humility asks us to acknowledge our imperfections. It requires that we admit when we are wrong and then change course. It counsels putting others first in thought, word, and deed, and it avoids the narcissistic self-promotion so rampant today.

Attractive in theory, humility sounds as though it will lead to failure in real life. As the conventional wisdom holds, humble folks must be shy and retiring, never forceful or magnetic. They have poor self-esteem and probably even hate themselves. They’re pushovers--meek, timid, and weak. To become humble in business, politics, or daily life is to give up on the possibility of high achievement.

Excessive pride obscures the idea that humility is the indispensable virtue for greatness. Humility hardly seems that good, let alone great. Greatness seems strong and energetic--anything but humble. “It’s hard to be humble,” Muhammad Ali is reported to have said, “when you’re as great as I am.”

The truth is that no one is naturally humble. Becoming humble, in fact, is an arduous process. George Washington, for example, had to struggle his entire life to become--and stay--humble. As a young man, his ego was enormous. Like the young Benjamin Franklin, his ambition outstripped his accomplishments.

Sometimes portrayed as a stolid, even stony man, Washington in real life was an individual of intense passions. His ability to rein them in has given us the impression today that he had none. This was not the case. A man of volcanic temper, vanity was a constant temptation for Washington; he knew he looked good in his military uniform (first British, then American) and so did the ladies around him. Arrogance of the sort that is heedless of others’ advice also plagued George Washington in his formative years.

An expert social climber and adept self-promoter, Washington displayed an early rashness on the battlefield that helped ignite a global conflagration. As he discovered, it is one thing to want to change one’s lot in life; it is another to be so eager to do so that the means of self-improvement do not matter. Greatness at any price is not real greatness.

In Washington’s early haste to achieve greatness, he sometimes let his ambition outpace his virtue. He gradually realized this, and he calibrated his actions accordingly. Rather than just cloaking his ambition, only to exert absolute rule when given the chance, Washington recognized that the more he served others and the cause of justice, the more his success would matter. The less his ambition was about his own fame, the more he would deserve the honors he received. Virtue in this sense, he discovered, can be its own reward.

Twice given dictatorial authority by the Continental Congress during the Revolutionary War, General Washington did not abuse his power. In fact, he laid down his sword after achieving America’s victory--at precisely the peak of power when most conquering generals throughout history have anointed themselves indispensable to political rule.

Greatness of soul spurs people to soar above the rest. Humility issues a warning against flying too high. For Benjamin Franklin, humility, however elusive, proved worth the effort. It made him, he reported late in life--long after his quest for “perfection” had failed--less quick with a harsh word and more ready to listen.

Franklin was 81 years old by the time the 1787 Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia. As the oldest delegate, he was also among the most respected. Franklin supported the Convention’s finished work product, but he knew it was imperfect. “The opinions I have had of its errors,” Franklin said on the last day of the four-month meeting, “I sacrifice to the public good.” Closing with an appeal for a unanimous vote in approval of the Constitution, Franklin asked everyone “to doubt a little of his own infallibility.”

In discovering his own fallibility, Franklin found a keener sense of imagination and a clearer vision for the future. In finding their way to humility, he and George Washington helped make a nation.

David J. Bobb, PhD, is author of Humility: An Unlikely Biography of America’s Greatest Virtue, forthcoming from Thomas Nelson, from which this article is adapted.

Source: Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, And The Power Of Humility In Leadership