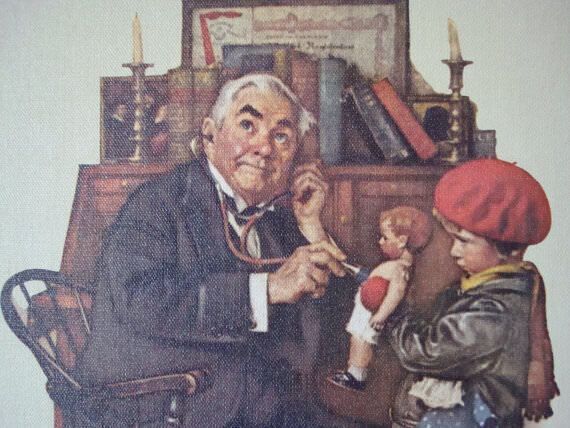

Doctor and Doll by Norman Rockwell

Professor Patrick Pietroni

Summary

The similarity between some spiritual practices present in many of the world’s religions and their secular counterparts is described. How these practices are incorporated within the work of a general practitioner is outlined and the pitfalls and problems are outlined.

Introduction

Holism espouses an awareness of the links between body, mind and spirit. Much is written about the first two, and the every expanding field of psychoneuroimmunology has allowed us to follow the pathways of how unhappiness enters a cell [1]. For many it is difficult to separate ‘spirit’ from mind. Yet ‘spirit’ implies more than emotional and psychological well-being. The divide between mind and spirit is not helped by the fact that psychoanalysis has incorporated the Greek word ‘psyche’, meaning soul, to describe mental structure. Without therefore defining spirit it would become increasingly difficult, if not impossible, to discuss whether such an entity as spiritual disease exists or not. Box 4.2 lists some of the many definitions that are used by theologians, the lay public and the dictionaries. The word ‘spirit’ is often linked with religious beliefs, be they Christian, Muslim or Buddhist. It is also associated with an experience, a sense of harmony or peace, a knowing from within. For others, ‘spirit’ is linked with the life-force (Chi-Prana) is closely linked with the breath or energy which helps to explain our own words, ‘inspired’ and ‘expired’.

| 4.2 What is spirit? |

| Immaterial part of man Religion//beliefs/conviction Soul-vitality Quintessence of various forms Life-force Breath of life A possession Something higher Inspired Emotional calmness Everyday ecstasy Sense of harmony Sense of belonging Knowing sure from within Transcendent force Mystical experience |

Michael Balint who wrote extensively on the psychological aspects of medicine, makes no direct mention of the interplay between spirit, mind and body. However, in his analytic articles, he comes close to a description of the spiritual dimension:

The aim of all human striving is to establish or probably re-establish an all-embracing harmony with one’s environment--to be able to love in peace.

The unio-mystica, the re-establishment of the harmonious interpenetrating mix-up between the individual and the most important parts of his environment, his love objects is the desire of all humanity [2].

Balint’s ‘interpenetrating mix-up’ is one of his most delightful phrases and captures the true nature of the best of general practice. Balint refers to two kinds of medicine, one where illness is seen as an accident arising from causes outside the patient and where the basis of rational therapy arises out of a theory about the causation of illness and the control of the presumed cause. The second is where illness is seen as a lack of integration between the individual and the environment and a meaningful phase in the patient’s life. Here meaning is used to imply purpose as opposed to cause. Finding a purpose and meaning to one’s life has always formed part of the ‘spiritual journey’ and is well described in all the world’s great religions. The Book of Job, Pilgrim’s Progress, Canterbury Tales, Siddhartha, Heart of Darkness, Don Quixote, Epic of Gilgamesh, are all stories of journeys where answers are sought to the perennial questions.

| 4.3 Spiritual practice and the general practice counterpart | |

| Spiritual practice | General practice counterpart |

| 1. Providing a sanctuary | Cosulting room as a 'safe space' |

| 2. Confessional | Active listening |

| 3. Interpret tribulation | Give meaning to stressful life events |

| 4. Source of ritual and ceremony | Repeat prescription |

| 5. Provide support and comfort | Teamwork |

| 6. Increase spiritual awareness | Give permission for spiritual discussion |

| 7. Laying on of hands; prayer and mediation | Use of touch |

| 8.Communion | Relaxation and quiet time; self-help groups/patient participation |

However, it may be more helpful for the general practitioner to avoid the complex and difficult world of theology and start from a very pragmatic base. What are the spiritual interventions associated with a priest or rabbi’s work and are any of these relevant to the needs of patients coming to see a doctor? And, more importantly, are these interventions practical within the context of general practice? Box 4.3 includes a list of spiritual practices common to many religions and the possible counterpart in a general practice setting.

Sanctuary/Safe Space

Churches were built not only as places of worship but also to serve as sanctuaries from invading forces. They were seen as sanctified territory providing the itinerant traveller with shelter and warmth. Spence describes the unit of medical practice as ‘the occasion when in the intimacy of the consulting room a person who is ill or believes himself to be ill seeks the advice of a doctor whom he trusts’ [3]. His words ‘intimacy’ and ‘trust’ invoke the notion of the consulting room as a ‘safe space’. The necessity for the ‘space’ to feel ‘safe’ applies equally well to the physical and psychological aspects of a general practitioner’s work. The atmosphere created by the architecture, the furniture, lighting, position of the desk, those personal possessions displayed, all help to create a sense of peace, or conversely, ‘business’ and disease. The chairs provided for patients to sit on can often ensure the patient feels anything but safe. Similarly, the ‘space’ of the consulting room needs to have its boundaries reasonably intact. Quality time is as important as quantity time, and interruptions by telephones, receptionists or partners will all help to create a feeling of ‘invasion’. One need only reflect on the different quality of interaction that occurs when seeing a patient in his or her own home to appreciate the effects that atmosphere and safety have on communication. Certainly the next six interventions are facilitated by ensuring that the consulting room feels safe for the patient.

Confessional/Active Listening

The act of unburdening oneself of troubled thoughts, feelings and resentments is an act that is as old as man. Since the notion of sin has been replaced with the notion of repression, the drama has moved from the confessional to the analytic couch. The general practitioner is neither a priest nor a psychoanalyst, yet possible we are told more secrets during th course of our work than either of those two professions. The Greek word ‘catharsis’ or cleansing may be more useful to the doctor than the word confessional. ‘Give up what thou hast and then they will receive’, ‘Confession is good for the soul’, A burden shared is a burden halved’: many psychotherapeutic techniques have been developed for aiding this process of unburdening, from the early use of hypnosis to free association. As Jung says though, ‘The goal of the cathartic method is full confessional--not merely the intellectual recognition of the facts with the head, but their confirmation by the heart and the actual release of suppressed emotion’ [4]. Heron provides an excellent overview of this process as it is utilized in many of the humanistic psychotherapies [5]. For the general practitioner, however, the ability of helping the patient to unburden himself needs to be carefully balanced by the realization that emotional curiosity does not always indicate caring. As Balint has well documented, knowing ‘when and how to stop’ a patient is even more important than knowing ‘how to start’. Nevertheless the skill required by the general practitioner for this aspect of his work is the ability to listen actively. This involves listening with the eyes as well as the ears. It involves indicating to the patient that you are present with him and requires the ability to communicate an empathic understanding. ‘It is important for the doctor to free himself from trying to discover why, so that he can observe how the patient talks, thinks, feels and behaves the way he does.’ [6] From time to time it may be necessary to give meaning or interpret tribulation but equally important is the ability to share, be with the avoid trying to find to find a solution. In hospital medicine, we are often told ‘Don’t just stand there, do something’. In general practice it is often necessary to remember ‘Don’t just do something, stand there’.

Example 1

Mrs. G., aged 45--series of repeated consultations for minor sore throats, coughs and ‘feeling tired’. On the fourth visit she was asked about her home life and this provided the stimulus for a long discussion about a long-standing affair and the fact that her partner was leaving London to change jobs. No attempt was made to give advice or suggest counseling and she volunteered 1 year later that she had ‘sorted her life out’ and was feeling a lot better.

Example 2

A 27-year-old Spanish man presented with the classical symptoms and signs of duodental ulcer, subsequently proved on X-ray. He had left his native country because of some misdemeanor and was much troubled and guilt-ridden. Even after unburdening himself he felt ill at ease. It transpired that he was a church-going Roman Catholic and felt he needed ‘absolution’ before his mind could rest in peace. He was reffered to his local church.

Provide Support and Comfort/Teamwork

The burden of caring for many isolated, lonely and distress patients in not one that doctors are able to handle on their own any longer. The move towards teamwork is not only a recognition of the need to share this burden amongst several healthcare practitioners, but also a recognition of the need of all healthcare practitioners to be themselves supported in this work. The general practitioner’s role, much like that of the priest, is to catalyze the family support, welfare services and community as well as the healthcare team. Knowing how to make the system work for the patient and acting as his or her advocate is often more beneficial and less strenuous than taking on the burden of caring for the patient directly.

Orchestrator of Ritual Rites and Ceremony/Giving Meaning to Stressful Life Events

Going to see the doctor or the monthly ‘chronic’ visit can on occasions serve as important a functions as the ritual of going to church every Sunday. The importance lies in the act itself, its repetitive nature and above all, its constancy. Balint’s work on the nature of repeat prescription well illustrated the need to see these meetings, not in purely medical terms. but serving a much more basic need of the human condition. Ceremonials, rituals and rites have traditionally formed the mode by which a culture aids individuals across the transition of important life events. Some of these transitions have been endowed with important religious significance (births, marriages, deaths). Yet others almost as common do not attract the attention of the pastor, rabbi or priest and often present themselves to the doctor in some form or other. Such transitions have been labelled ‘rites of passage’ and as Holmes & Rahe have shown, whether happy or unhappy, these life events are points of stress [7]. Whether these life events lead to a breakdown and break-up or breakthrough and ‘growth’ can depend on how they are managed by the individual, his family and his advisers, including his doctor.

The doctor may choose to medicalize the problem and revert to the first sort of medical practice as described by Balint. He may, however, choose to raise the discussion between himself and the patient to explore the meaning of the problem.

Example 1

Miss C., aged 25, came in for medical examination, applying for a university place in America, mentioned many minor complaints. Parents form Syria--she was brought up in England. During the course of the consultation she was asked “Can you see a purpose to your life?’ which brought about an immediate discussion of the conflict of cultures she experienced and her wish to ‘run away from home’, her fear of intercourse with her boyfriend and a sense of panic she felt when faced with decisions. This young lady presented the doctor with many different problems:

Physical--headaches, tiredness, vaginismus.

Psychological--depression, poor self-esteem, lack of identity

Spiritual--lack of purpose, sense of alienation, loss of belief in system (‘I don’t know what is right or wrong any more’).

Many similar examples could be given from every general practitioners’s daily workload and it is clear that a spiritual dimension could be included, if the doctor so wishes, in many consultations. It is only with a few, however, that the opportunity arises and the right ‘interpenetration harmonious mix-up’ will result in a shift from the ordinary consultation to the extraordinary. Other possible ‘rites of passage’ are outlined in Box 4.4 and other forms of ‘spiritual’ questions in Box 4.5

| 4.4 Rites of passage (stressful life events) | |

| New patient | Bereavement |

| Birth | Adoption |

| Death | Going on the pill |

| Infertility | Fitness medical |

| Terminination | Retirement |

| Marriage | New employment |

| Divorce | Unemployment |

| Attempted suicide | Entering accomodation |

| Leaving home |

Entering or leaving prison |

| 4.5 Spiritual questions |

|

Are you a a religious person? Do you pray? Is prayer important to you? Do you believe in God? Does your life have a purpose? Are you a church-going person? Do you believe in an after-life? Have you thought about your death? |

Example 2

54-year old Bangladeshi man complaining of painful knees, for which no obvious physical cause could be found. He was asked whether he prayed and whether his pain interfered with his prayer. This caused an immediate ‘deepening’ of the consultation and he talked about the ‘cold weather’ in England and the difficulty he experienced kneeling down. He also acknowledge his isolation and loneliness (his wife died soon after they had arrived in England).

Communion/Group Work/Clinics

For most Christians, the act of going to Church not only serves as a reminder of the Trinity but is also an act of coming together to receive a blessing or sacrament. This coming together of people can be seen as a ‘healing ceremony’ and is to be witnessed in both secular and sacred forms. We have tended to individualize our encounters between doctor and patient and have forgotten the importance, power and significance of a group One of the benefits of ante-natal clinics, and mother and toddler groups, lies in the sharing that occurs between the people attending. Similarly, the explosion of self-help groups could be seen as serving the need to bring people together in ‘communion’. The need for a collective experience is often made possible through a shared illness. It would be interesting to ponder whether we could be more effective seeing our 10 patients together for 1 hour as opposed to giving them 6 minutes each. The two groups of patients that require most attention from the general practitioner are the elderly, isolated and the anxious, neurotic (usually young) Organizing a method by which these two groups could come together would be a fascinating project. Our own efforts have been in the organization of ‘stress classes’ where simple coping skills are taught to a group of patients. These groups have developed to the extend that ‘ex-patients’ are now able to take new groups through the six sessions.

| 4.15 Psychophyslogical changes in meditation | ||

| Pulse rate | ^ | 10/min |

| Blood pressure | - | 20% |

| Blood lactate | ^ | |

| Gas exchange |

^ - |

O2 consumption CO2 elimination |

| Prolacin | - | |

| Cortisol | - | Psychological stability |

| EEG alpha wave | ^ | Internal locus of control |

| Carry-over effects | ^ | |

Prayer and Meditation/Relaxation and Quiet Time

The last 20 years have seen an explosion of interest in the use of breathing and relaxation technique and their application to medical conditions (asthma, hypertension, migraine). Meditation, as a secular act, can be described as a state of relaxed non-aroused physiological functioning which can help to liberate the mind from disturbing and distracting emotions. Table 4.15 details some of the alterations that occur both during and after meditation.

Teaching patients the importance of a ‘quiet time’ or meditation through the use of an audio-cassette or classes can provide them with the ‘breathing space’ that so many people need in their lives. The 10-minute appointment slot is perfectly suited for a joint-meditation and I have at least one or two patients each day who come in solely to meditate in the consulting room. It is an activity that is as beneficial to the doctor as it is to the patient.

Laying on of Hands/Touch

Touching, layering on of hands and blessing have always formed part of spiritual practices and their therapeutic effects have been recognized through such terms as ‘the King’s touch’, ‘the healing touch’, etc. Citing many examples from animal and human behavior, Montagu points out how the skin and touching form an essential psychological and physiological first step in the proper development of the other sensory systems of the body [8]. Deprivation dwarfism is a well-recognized condition that occurs in institutions where children, in spite of good food and medical care, fail to thrive because they are not petted and cossetted. As doctors we are a specially privileged group allowed to touch more people in more places than almost every other profession bar one. However, as we have become more scientific, we have tended to reject this powerful gift to the detriment of our patients. Among the many reasons why people are turning to alternative medicine is the fact that many of these therapies are contact-based (osteopathy, massage, reflexology, acupuncture, etc.).

There is now good laboratory and clinical evidence to indicate the therapeutic use of touch and we can, if required, quote numerous scientific studies in support. By the simple act of touching, the doctor can reaffirm to the patient that he, the patient, is a unique person and their interaction is altogether human. This can be achieved simply through a sincere handshake. A cold limp hand held out reluctantly induces the opposite effect. We do not hesitate to touch, hold or even sit a child on our knee when talking to him. There is no risk involved in the misinterpretation of this act. There is indeed a risk if we were to do this with our adult patients. For touching to be effective it must:

- be acceptable to the patient

- be acceptable to the doctor

- be recognized that it has a unique meaning for each patient.

Touch as a method of communication differs according to culture as well as age and sex. Within each culture there are enormous variables and we may instinctively recognize this. Children usually have no say--wrongly so--as to whether they are touched or not. Adults may well fee uneasy and threatened by touch.

Touch should be used in a supportive way--meeting the patient’s unsatisfied needs while allowing him to remain as independent as possible. Doctors approaching patients on whom they have to do an internal examination often start by introducing the speculum. A few seconds spent holding the patients’ hands or placing the hand on the abdomen makes the examination easier for both the doctor and the patient. When examining a patient not only can one’s hands be used as scientific probes for underlying disease, they can at the same time reassure and comfort the patient that there is a human being guiding those probes. Too often doctors poke instead of touch--and the sexual comparison is more than apt--with the subsequent unsatisfactory intercourse and frigidity. It is because of this sexual conflict that touching in the medical consultation has been so restricted. This may on occasions be justified. When examining a woman’s breasts, a male doctor may well be aware that she is conscious of them as sexual objects, as indeed may the woman doctor. Asking about dyspareunia, however, is often best left till the pelvic examination. Not only does this appear sensible from a purely factual point of view, it also indicates to the patient that the doctor is really interested as to precisely where it hurts.

Kathryn Barnet [9], in an excellent paper on the concept of touch as it relates to nursing, summarizes her propositions and suggestions for further research as follows:

- The greater the patient’s sense of isolation and sensory deprivation, the greater his need for relatedness to others through touch.

- The greater the patient’s altered body image, the greater his need for acceptance through touch.

- The greater the patient’s feeling of depersonalization, the greater his need for identity through touch.

- The greater the patient’s regression, the greater his need for communication through touch.

- The greater the patient’s anxiety, the greater the nurse’s responsibility regarding the appropriateness of the use of touch.

- The greater the patient’s dependency, the greater the nurse’s responsibility regarding the appropriateness of use of touch.

- The greater the patient’s self-concealment, the greater his need for communication through touch.

- The greater the patient’s need for privacy, the lesser his need for touch.

- The greater the patient’s need for territorial imperative, the lesser his need for touch.

- The letter the patient’s self-esteem, the greater his need for confirmation through touch.

- The greater the patient’s sense of rejection, the greater his need for acceptance through touch.

- The greater the patient’s fear of death, the greater his need for relatedness to others through touch.

Discussion

There are many omissions to this descriptive account of ‘spiritual practices in general practice’ and little attempt has been made to describe the pitfalls and problems involved for the general practitioner, least of which is the need to ensure that ‘spiritual’ enquiry is not a cover for physical and psychological incompetence. In addition, the separation of the ‘religious’ element from the secular is artificial and may lead to the loss of the importance of awe, wonder and mystery. The practitioner’s own spiritual beliefs and spiritual practices will inform his/her approach, and the necessity for maintaining and tolerating an appropriate level of uncertainty seems even more necessary than in the physical and psychological domains. It may be that:

the touch of the healer although it may be like the touch of the masseur is probably quite different. The touch of the mystic, the touch of the religious man, may have a special quality and it is this elusive and spiritual aspect that guides and fires the dimension which may give it power that what one might call the ‘secular touch’ does not have. [10]

This paper illustrates that doctors have a lot to learn from the other caring disciples. Hopefully it will provide a stimulus for others to continue in this area of inquiry.

References

- Locke, Hornig-Rohan, Mind and Immunology; Institute for Advancement of Health, 1985.

- Balint M. The base fault. Tavistock, 1984.

- Horder, J. RCGP. The future general practitioner: learning and teaching. British Medical Journal, 1972.

- Jung, C.J. Collected works, volume 16. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981, p. 59.

- Heron, J. Catharsis in human development. British Postgraduate Medicatl Federation, 1977.

- Balint, M. Six minutes for the patient. Tavistock, 1973.

- Holmes, T. Rahne, R.H. The social readjustment scale. J. Psychosom, Res 1967 11L 213.

- Montagu, A. Touching: the human significance of the skin. Harper and Row, 1971.

- Barnet, K.A. Theoretical constructs of the concept of touch.

- Fry, A. (Personal communication).

Source: Reprinted with permission from Holistic Medicine I; pp. 253-262, published by John Wiley & Sons.

← Go back Next page →