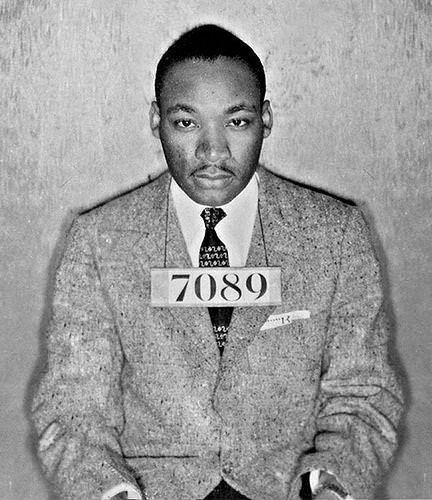

“I arose early on Sunday morning—a custom I follow every Sunday in order to have an hour of quiet meditation.”

~ Martin Luther King

by Benjamin Riggs

As a child, I spent many a Sunday mornings drawing dinosaurs, airplanes, and rocket-ships on the back of offering envelopes at the Waskom, Texas Baptist church.

I loved that church.

I loved the ride to church. I always sat next to the same man on the church bus—his name was Jimmy, I think—he had Down syndrome and he loved to sing, boy did he love to sing. My favorite number he would perform was the Bob Seger classic, “I Like that Ole Time Rock-&-Roll.”

I met my first girlfriend at that church. I ran home one Sunday afternoon excited about this giant leap toward something—wasn’t quite sure what—only to be told, “We don’t date black girls.”

It’s interesting to me that this is some ‘thing’ I had to be taught. Martin Luther King once said, “We must rapidly begin the shift from a ‘thing-oriented’ society to a ‘person-oriented’ society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism and militarism are incapable of being conquered.”

We come into this world without ‘things.’ We come into this world seeing people. We are taught to see things.

What is a thing?

In order to measure a curve you must install points. You must fix upon this crooked line various points and measure the distance between them. So it is with things…

Life is a curve. Our life is fluid and in order to measure it we install fixed reference points. These reference points are ‘things.’ Things are thoughts. They are practically the same word, as Alan Watts cleverly pointed out when he said, “a thing is a think.” A thing is a label, a name, a point used to measure our experience, a curve.

Why is this important?

‘Things,’ in-&-of themselves, are not problematic. They are useful social conventions that enable us to communicate and share ideas with one another—to commune. It is our attachment to things that is problematic.

We ‘think’ about ‘things’ too much.

It is, as Dr. King alluded to in the before mentioned quote, our orientation toward things that is of concern. We become attached to things, and since ‘things’ are ‘thinks’ an attachment to things is an addiction to thought. Simply put, we think about our own thoughts until we lose touch of the surface we set out to measure. There is nothing wrong with taking a measurement, but problems tend to arise when we mistake the map for the territory.

The metric system used to measure life is the ego. It is what we think about our self. If some ‘thing’ or someone affects us in a positive way, we consider them a friend or the love of our life; if they affect us in a negative way, we consider them an enemy or an asshole; on the other hand, if they fail to affect us in a positive or negative way they do not pop up on our radar. We do not ‘think’ about them at all. They are not worthy of being a ‘thing.’ So, it is the ego—what we ‘think’ about ourselves—that is the common denominator.

‘I’ is the original ‘thing.’ It is the first ‘think.’ This is what it means to be self-centered. The whole world is defined by or measured against, our self image. This produces a narrow, prejudiced mind. It is like using a ruler to measure its own length. If some ‘thing’ fails to reflect our image, then it doesn’t measure up, which is to say that it is worthless or evil.

Insanity is a point of view inspired, not by the present moment, but by the previous thought. We think about our own thoughts for so long we lose sight of reality. We are out of touch—we no longer feel life; we only hear what we think about life, our commentary. We see our version, which is delusion. We see only our measure of life. When we look at a person we do not see a person, but a thing: a liberal, a conservative, a friend or enemy.

Likewise, when others look at us, they do not see a person, they see their own thoughts. And just as we exist independent of what they think about us, they exist, not as ‘things’ but as people independent of what we ‘think.’

This state of independence is called freedom.

Not only do ‘I’ exist independent of what ‘they’ think, but in some sense, ‘I’ {capital “I “} exist independent of what ‘i’ {lower-case “i ”} think. This inner-freedom is silence. Our true nature is emptiness. We came into this world without a name, and still—right now, this very second—who we actually are is nameless. We may get caught up in thinking about our self, thereby thingifying our Self. We may get all wrapped up in our names and our titles—husband, wife, son, daughter, friend, enemy—but in the final analysis who we actually are is much too vast to be measured or encompassed by thought. Our true nature is thinglessness.

In silence we reconnect with the immediacy and precision of our true life by letting go of what we ‘think’ about ourselves and the world we live in. In silence, we move beyond all the differentiating levels of consciousness—all the points placed along the curve—and resurrect the universal spark of humanity that animates us all. Not in a theoretical sense, but in a real and meaningful way we step beyond the layers of thingness that obscure our vision and reconnect with the deep and abiding sense of personhood embedded in our body.

Meditation practice is the practical application of silence.

In mediation we consent to silence—that state of indwelling freedom beyond what we think about ourselves. In silence there is no sense of self. There is no “my” happiness or “your” suffering; no “my” wealth and “your” poverty. Through meditation practice we come to realize, first hand, what Dr. King meant when he said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

Through meditation practice we come to embody compassion and compassion changes the world.

Source: http://www.elephantjournal.com/2014/01/how-sitting-on-the-floor-in-silence-changes-the-world/?utm_source=All&utm_campaign=Daily+Moment+of+Awake+in+the+Inbox+of+Your+Mind&utm_medium=email