by Maria Popova

“If we ever reach the point where we think we thoroughly understand who we are and where we came from, we will have failed.”

I was recently on NPR’s Science Friday to discuss my favorite science books of the year and a listener called in, asking for a recommendation for a good book on science and religion — an excellent question, given the long history of this polarization, which occupied great minds from Galileo to Einstein to Ada Lovelace to Isaac Asimov, and many more.

I was recently on NPR’s Science Friday to discuss my favorite science books of the year and a listener called in, asking for a recommendation for a good book on science and religion — an excellent question, given the long history of this polarization, which occupied great minds from Galileo to Einstein to Ada Lovelace to Isaac Asimov, and many more.

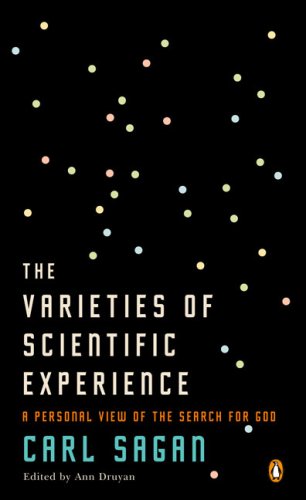

The best book on the subject, by far, is The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God (public library) — a remarkable posthumous collection of essays by Carl Sagan, based on the prestigious Gifford Lectures on Natural Theology he delivered at the university of Glasgow in 1985, following in the footsteps of such celebrated philosophers as James Frazer, Arthur Eddington, Werner Heisenberg, Niels Bohr, Alfred North Whitehead, Albert Schweitzer, and Hannah Arendt. Titled after the famous treatise on religion by William James, who delivered the Gifford Lectures in the beginning of the twentieth century, this anthology of illustrated and illustrious meditations showcase Sagan’s singular gift for championing knowledge with equal parts conviction and humility.

Sagan’s widow, Ann Druyan — the love of his life and the greatest bastion of his legacy — contextualizes the lectures in the introduction:

Carl Sagan was a scientist, but he had some qualities that I associate with the Old Testament. When he came up against a wall—the wall of jargon that mystifies science and withholds its treasures from the rest of us, for example, or the wall around our souls that keeps us from taking the revelations of science to heart—when he came up against one of those topless old walls, he would, like some latter-day Joshua, use all of his many strengths to bring it down.

[…]

He believed that the little we do know about nature suggests that we know even less about God. We had only just managed to get an inkling of the grandeur of the cosmos and its exquisite laws that guide the evolution of trillions if not infinite numbers of worlds. This newly acquired vision made the God who created the World seem hopelessly local and dated, bound to transparently human misperceptions and conceits of the past.

[…]

Carl wanted us to see ourselves not as the failed clay of a disappointed Creator but as starstuff, made of atoms forged in the fiery hearts of distant stars. To him we were “starstuff pondering the stars; organized assemblages of 10 billion billion billion atoms considering the evolution of atoms; tracing the long journey by which, here at least, consciousness arose.” For him science was, in part, a kind of “informed worship.” No single step in the pursuit of enlightenment should ever be considered sacred; only the search was.

It is befitting that Druyan should title the collection this way, since Sagan greatly admired James’s definition of religion as “feeling of being at home in the Universe,” even using the phrase in the conclusion to his iconic Pale Blue Dot. In the first lecture, titled “Nature and Wonder: A Reconnaissance of Heaven,” Sagan begins by exploring the cultural and psychological commonalities between science and religion:

It is befitting that Druyan should title the collection this way, since Sagan greatly admired James’s definition of religion as “feeling of being at home in the Universe,” even using the phrase in the conclusion to his iconic Pale Blue Dot. In the first lecture, titled “Nature and Wonder: A Reconnaissance of Heaven,” Sagan begins by exploring the cultural and psychological commonalities between science and religion:

The word “religion” comes from the Latin for “binding together,” to connect that which has been sundered apart. It’s a very interesting concept. And in this sense of seeking the deepest interrelations among things that superficially appear to be sundered, the objectives of religion and science, I believe, are identical or very nearly so. But the question has to do with the reliability of the truths claimed by the two fields and the methods of approach.

By far the best way I know to engage the religious sensibility, the sense of awe, is to look up on a clear night. I believe that it is very difficult to know who we are until we understand where and when we are. I think everyone in every culture has felt a sense of awe and wonder looking at the sky. This is reflected throughout the world in both science and religion. Thomas Carlyle said that wonder is the basis of worship. And Albert Einstein said, “I maintain that the cosmic religious feeling is the strongest and noblest motive for scientific research.” So if both Carlyle and Einstein could agree on something, it has a modest possibility of even being right.

And yet religions, Sagan argues, use this sense of awe to suppress rather than expand our sense of self:

Many religions have attempted to make statues of their gods very large, and the idea, I suppose, is to make us feel small. But if that’s their purpose, they can keep their paltry icons. We need only look up if we wish to feel small. It’s after an exercise such as this that many people conclude that the religious sensibility is inevitable.

Even more powerful and discomfiting than our sense of smallness is the sense of impermanence that a true contemplation of the universe gives us, a sense that most religions work very hard to counter with promises of an afterlife or other mediatory concepts. Sagan writes:

All that we have seen is something of a vast and intricate and lovely universe. There is no particular theological conclusion that comes out of an exercise such as the one we have just gone through. What is more, when we understand something of the astronomical dynamics, the evolution of worlds, we recognize that worlds are born and worlds die, they have lifetimes just as humans do, and therefore that there is a great deal of suffering and death in the cosmos if there is a great deal of life.

How is one not to love a scientist who aligns his argument with one of history’s greatest poets? Sagan adds:

And if … life and perhaps even intelligence is a cosmic commonplace, then it must follow that there is massive destruction, obliteration of whole planets, that routinely occurs, frequently, throughout the universe. Well, that is a different view than the traditional Western sense of a deity carefully taking pains to promote the well-being of intelligent creatures. It’s a very different sort of conclusion that modern astronomy suggests. There is a passage from Tennyson that comes to mind: “I found Him in the shining of the stars, / I mark’d Him in the flowering of His fields.” So far pretty ordinary. “But,” Tennyson goes on, “in His ways with men I find Him not…. Why is all around us here / As if some lesser god had made the world, / but had not force to shape it as he would…?”

In fact, Sagan considers religion’s concept of God not too overwhelming but too constricted, too small. He goes on to read a passage from Thomas Payne’s Age of Reason:

“From whence, then, could arise the solitary and strange conceit that the Almighty, who had millions of worlds equally dependent on his protection, should quit the care of all the rest, and come to die in our world because, they say, one man and one woman ate an apple? And, on the other hand, are we to suppose that every world in the boundless creation had an Eve, an apple, a serpent, and a redeemer?”

Paine is saying that we have a theology that is Earth-centered and involves a tiny piece of space, and when we step back, when we attain a broader cosmic perspective, some of it seems very small in scale. And in fact a general problem with much of Western theology in my view is that the God portrayed is too small. It is a god of a tiny world and not a god of a galaxy, much less of a universe.

Reminding us that ignorance is the root of progress, Sagan writes:

I don’t propose that it is a virtue to revel in our limitations. But it’s important to understand how much we do not know.

He plays devil’s advocate to a common religious resistance to scientific inquiry:

Does trying to understand the universe at all betray a lack of humility? I believe it is true that humility is the only just response in a confrontation with the universe, but not a humility that prevents us from seeking the nature of the universe we are admiring. If we seek that nature, then love can be informed by truth instead of being based on ignorance or self-deception. If a Creator God exists, would He or She or It or whatever the appropriate pronoun is, prefer a kind of sodden blockhead who worships while understanding nothing? Or would He prefer His votaries to admire the real universe in all its intricacy? I would suggest that science is, at least in part, informed worship.

In the second lecture, titled “The Retreat from Copernicus: A Modern Loss of Nerve,” Sagan reminds us just how solipsistic our model of the universe and “God” is in the grand scheme of existence and cosmic time:

If the Earth is, as we certainly know it to be, 4,500 million years old and the human species at most a few million years old, probably less than that, then we have been here for only an instant of geological time, for less than one one-thousandth of the history of the Earth, and therefore in time, as in space, we have been demoted from the central to an incidental aspect.

[…]

If the very strong version of the anthropic principle is true, that is, that God—we might as well call a spade a spade—created the universe so that humans would eventually come about, then we have to ask the question, what happens if humans destroy themselves? That would make the whole exercise sort of pointless. So if only we could believe the strong version, we would have to conclude either (a) that an omnipotent and omniscient God did not create the universe, that is, that He was an inexpert cosmic engineer, or(b) that human beings will not self-destruct. Either alternative, it seems to me, is a matter of some interest, would be worth knowing. But there is a dangerous fatalism lurking here in the second branch of that fork in this road.

Science, to Sagan, is the antidote rather than the source of this fatalism. He ends the third lecture, titled “Organic Universe,” with “a beautiful little piece of poetry” by a woman in rural Arkansas named Lillie Emery who, while not a professional poet, does write poetry and had sent some to Sagan:

My kind didn’t really slither out of a tidal pool, did we?

God, I need to believe you created me: we are so small down here.

To Sagan, Emery’s verse captures the quintessential human fear that fuels underpins both the consolation of religion and the promise — the essence — of science. He reflects:

I think there is a very general truth that Lillie Emery expresses in this poem. I believe everyone on some level recognizes that feeling. And yet, and yet, if we are merely matter intricately assembled, is this really demeaning? If there’s nothing in here but atoms, does that make us less or does that make matter more?

In the ninth lecture, aptly titled “The Search,” Sagan reveals that, for him as well as for science, it is the search rather than the find that is most illuminating, and that, like the humanities, science is above all an antidote to solipsism:

If Newton were restricted, in working through the theory of gravitation, to apples and forbidden to look at the motion of the Moon or the Earth, it is clear he would not have made much progress. It is precisely being able to look at the effects down here, look at the effects up there, comparing the two, which permits, encourages, the development of a broad and general theory. If we are stuck on one planet, if we know only this planet, then we are extremely limited in our understanding even of this planet. If we know only one kind of life, we are extremely limited in our understanding even of that kind of life. If we know only one kind of intelligence, we are extremely limited in knowing even that kind of intelligence. But seeking out our counterparts elsewhere, broadening our perspective, even if we do not find what we are looking for, gives us a framework in which to understand ourselves far better.

I think if we ever reach the point where we think we thoroughly understand who we are and where we came from, we will have failed. I think this search does not lead to a complacent satisfaction that we know the answer, not an arrogant sense that the answer is before us and we need do only one more experiment to find it out. It goes with a courageous intent to greet the universe as it really is, not to foist our emotional predispositions on it but to courageously accept what our explorations tell us.

Following the essay is a small selection of the best Q&As Sagan received after each of his original lectures. In one, he addresses the notion of “God” with more directness and clarity than he does in any of the actual essays, exposing the human search at the root of the notion with exquisite precision:

The word “god” is used to cover a vast multitude of mutually exclusive ideas. And the distinctions are, I believe in some cases, intentionally fuzzed so that no one will be offended that people are not talking about their god.

But let me give a sense of two poles of the definition of God. One is the view of, say, Spinoza or Einstein, which is more or less God as the sum total of the laws of physics. Now, it would be foolish to deny that there are laws of physics. If that’s what we mean by God, then surely God exists. All we have to do is watch the apples drop.

Newtonian gravitation works throughout the entire universe. We could have imagined a universe in which the laws of nature were restricted to only a small portion of space or time. That does not seem to be the case. … So that is itself a deep and extraordinary fact: that the laws of nature exist and that they are the same everywhere. So if that is what you mean by God, then I would say that we already have excellent evidence that God exists.

But now take the opposite pole: the concept of God as an outsize male with a long white beard, sitting in a throne in the sky and tallying the fall of every sparrow. Now, for that kind of god I maintain there is no evidence. And while I’m open to suggestions of evidence for that kind of god, I personally am dubious that there will be powerful evidence for such a god not only in the near future but even in the distant future. And the two examples I’ve given you are hardly the full range of ideas that people mean when they use the word “god.”

But arguably the most powerful and timeless manifestation of Sagan’s position on science and religion comes from something never intended for public eyes. Druyan writes:

In that same drawer where the transcript of these lectures was rediscovered, there was a sheaf of notes intended for a book we never had the chance to write. Its working title was Ethos, and it would have been our attempt to synthesize the spiritual perspectives we derived from the revelations of science. We collected filing cabinets’ worth of notes and references on the subject. Among them was a quotation Carl had excerpted from Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), the mathematical and philosophical genius, who had invented differential and integral calculus independently of Isaac Newton. Leibniz argued that God should be the wall that stopped all further questioning, as he famously wrote in this passage from Principles of Nature and Grace:

“Why does something exist rather than nothing? For ‘nothing’ is simpler than ‘something.’ Now this sufficient reason for the existence of the universe…which has no need of any other reason…must be a necessary being, else we should not have a sufficient reason with which we could stop.”

And just beneath the typed quote, three small handwritten words in red pen, a message from Carl to Leibniz and to us: “So don’t stop.”

The Varieties of Scientific Experience is a sublime read in its entirety, the kind that gives you instant pause, then stays with you for a lifetime. Complement it with Sagan on mastering the vital balance between openness and skepticism and the meaning of life, and Neil DeGrasse Tyson on Sagan’s legacy.