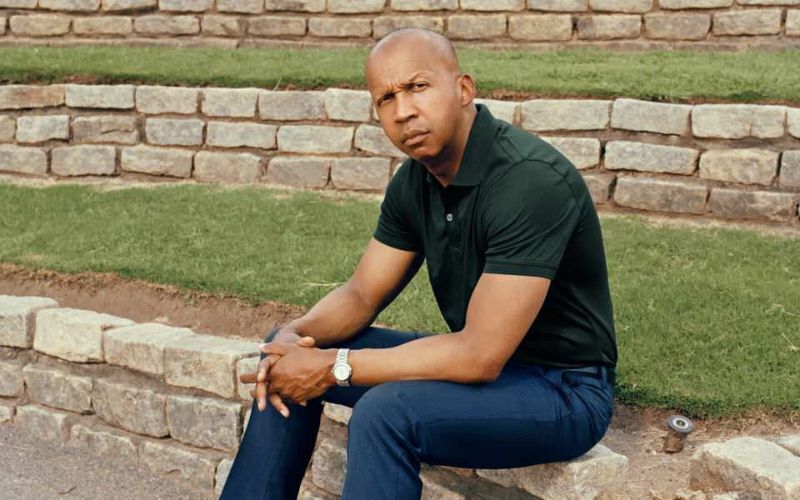

Photograph by Ryan Pfluger for The New Yorker

Stevenson’s Memorial for Peace and Justice will commemorate some four thousand lynching victims in twelve states.

In Alabama, Bryan Stevenson is saving inmates from execution and memorializing the darkest episodes of America’s past.

1989, a twenty-nine-year-old African-American civil-rights lawyer named Bryan Stevenson moved to Montgomery, Alabama, and founded an organization that became the Equal Justice Initiative. It guarantees legal representation to every inmate on the state’s death row. Over the decades, it has handled hundreds of capital cases, and has spared a hundred and twenty-five offenders from execution. In recent years, Stevenson has also argued the appeals of prisoners around the country who were convicted of various crimes as juveniles and given long sentences or life in prison. One was Joe Sullivan, who was thirteen when he was charged in a sexual battery in Pensacola, Florida. Sullivan’s original trial, in 1989, established that he and two older boys had burglarized the home of a woman named Lena Bruner on a morning when no one was there. That afternoon, Bruner was sexually assaulted in the home by someone whose face she never saw. The older boys implicated Sullivan, and he was convicted. They served brief sentences. Sullivan was sentenced to life in prison, with no possibility of parole.

In 2005, the Supreme Court decided Roper v. Simmons, a landmark ruling that held that states could no longer execute offenders who had committed their crimes before the age of eighteen. At the time, the Equal Justice Initiative had several clients in Alabama who had been charged when they were teen-agers and were now exempt from execution. To inform them of the ruling, Stevenson went to death row at the Holman Correctional Facility. He described his visit to me as we sat in his windowless office at E.J.I.’s headquarters, a converted warehouse in downtown Montgomery.

“When I went down and started talking to the guys and said, ‘I’ve got great news, they’re not going to execute,’ it wasn’t, like, joy, because they were all still quite young,” Stevenson recalled. “It was just another kind of death sentence. ‘Oh, seventy more years in prison.’ ”

But Stevenson saw an opportunity in the Roper ruling. “The Court was saying, in a categorical way, ‘Look, children are fundamentally different from adults.’ ” If the Supreme Court ruled that children were too immature to be sentenced to death, Stevenson reasoned, then they shouldn’t be sentenced to life, either. In order to push for an extension of Roper, he needed to find a test case. He began a nationwide search for inmates who had been convicted of crimes as juveniles and sentenced to life without parole.

Joe Sullivan is forty now, and he lives in the Graceville Correctional Facility, a privately run prison in a remote part of northern Florida. His speech is halting and slurred, owing to a long-standing mental disability and to multiple sclerosis, which was diagnosed more than twenty years ago. “I didn’t do nothing,” Sullivan told me. “I was just with the wrong people at the wrong time. They said I’m the mastermind to everything. They said I did a sexual battery. I couldn’t spell ‘sex’ in those days.”

On November 9, 2009, Stevenson stood before the nine Justices of the Supreme Court and began, “Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the Court: Joe Sullivan was thirteen years of age when he was arrested with two older boys, one fifteen and one seventeen, charged with sexual assault, ultimately convicted, and sentenced to life without parole. Joe is one of only two children this age who have ever been sentenced to life without parole for a non-homicide, and no child has received this sentence for non-homicide in the last eighteen years.” The Justices dismissed Sullivan’s case on procedural grounds, but in a companion case, argued earlier that day, they had embraced Stevenson’s argument: juveniles in non-homicides could not be sentenced to life.

After the decision, Stevenson took Sullivan’s case back to the Florida trial court for resentencing. In light of Sullivan’s record in prison, the Florida Department of Corrections informed him that he would be released on June 30, 2014. Sullivan had had a rough time in custody. As a young teen in an adult state prison, he had been the victim of numerous sexual assaults. His current prison was not a violent place, Sullivan told me, but his M.S. had got much worse. “As he became someone who couldn’t walk, and needed a wheelchair, the state was terrible in recognizing his needs,” Stevenson said. “He was basically in a dorm where he was forced to walk places. This caused mini seizures, which will leave him more impaired.” Sullivan had had only sporadic contact with his family over the years, and his only visitors came from E.J.I. In anticipation of his release, Stevenson rented a wheelchair-accessible apartment for Sullivan just outside Montgomery. “Mr. Bryan, he’s like my father,” Sullivan told me. “He gave me a lot of hope.”

Three weeks before Sullivan’s scheduled release, he received a notice from the Department of Corrections stating that his release date had been miscalculated. The correct date was December, 2019—more than five years later. Stevenson has gone back to court to challenge the department’s determination, but Sullivan remains incarcerated. (State officials have declined to comment.) “It’s been very frustrating,” Stevenson said. “We were just all set. Joe sent me a Father’s Day card. It breaks your heart.” Sullivan remains hopeful. “I say, ‘push yourself every day,’ ” he told me. “push—Pray Until Something Happens.”

Was the Sullivan case a success or a failure? It was, in one sense, a great victory, because Sullivan, who was facing the prospect of dying in prison, will now be released at some point. But, almost three decades after he was incarcerated, he remains in prison, in a wheelchair. Of course, Stevenson has experienced grimmer disappointments in his career as a death-row lawyer. Stephen Bright, the president and senior counsel of the Southern Center for Human Rights, told me, “Many people do this work only for a period of time. It’s a very brutal practice. Your clients get killed.”

“I don’t get all the hype about treadmill desks.”

Stevenson and his colleagues have managed to slow, but not stop, the death-penalty machinery in Alabama—an enormous challenge in view of the state’s conservative and racially polarized politics. Alabama has an elected judiciary, and candidates compete to be seen as the toughest on crime. It’s also the only death-penalty state in which judges routinely overrule juries that vote against imposing death sentences. (In their campaigns, judges boast about the number of death sentences they’ve imposed.) Alabama’s population is about twenty-seven-per-cent African-American. The nineteen appellate judges who review death sentences, including all the justices on the state Supreme Court, are white and Republican. Forty-one of the state’s forty-two elected district attorneys are white, and most are Republican. The state imposes death sentences at the highest rate in the nation, but the Equal Justice Initiative has limited the number of executions to twenty-two in the past decade, and there has been only one in the past three years. “It’s just intensive case-by-case litigation,” Stevenson told me. “We’ve gone more aggressively than anyone in the country on racial bias against African-Americans in jury selection. We have extensive litigation on the lethal-injection protocols. We identify inadmissible evidence. We push hard on every issue.”

But Stevenson, who is fifty-six, has come to believe that the defense of people enmeshed in the criminal-justice system, while indispensable, is an inadequate response to the deeper flaws in American society. He served on President Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, and he has been an ally of the Black Lives Matter movement. The recent police shootings of African-American men in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and outside St. Paul, Minnesota, have increased his pessimism. “These police shootings are symptoms of a larger disease,” he told me. “Our society applies a presumption of dangerousness and guilt to young black men, and that’s what leads to wrongful arrests and wrongful convictions and wrongful death sentences, not just wrongful shootings. There’s no question that we have a long history of seeing people through this lens of racial difference. It’s a direct line from slavery to the treatment of black suspects today, and we need to acknowledge the shamefulness of that history.”

After a ted talk in 2012, called “We Need to Talk About Injustice,” Stevenson is said to have received the longest standing ovation of any speaker, and the talk has been viewed more than five million times on the Internet; it raised a million dollars for his organization, and propelled a death-row lawyer into a public figure. His 2014 memoir, “Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption,” spent years on best-seller lists. He is in constant demand as a lecturer across the country, and he’s booked for commencement addresses years in advance.

As a longtime resident of Montgomery, he often thinks about Rosa Parks, whose refusal to sit at the back of a local bus in 1955 set off the modern era of the civil-rights movement. “We have reduced her activism to this celebratory tale—‘It was all great,’ ” he told me. “Here’s what most people don’t know. After the boycott was declared officially over, and black people were sitting on the buses, there was unbelievable violence. There were a dozen people who were shot standing waiting on buses. We had white people going around Montgomery shooting black people who dared to get on the buses.” For a time after the boycott, the city shut down bus service altogether. And then, to make way for the I-85 highway, the local authorities, led by a state transportation commissioner who was also a member of the Ku Klux Klan, bulldozed the city’s major middle-class black neighborhood.

Stevenson believes that too little attention has been paid to the hostility of whites to the civil-rights movement. “Where did all of those people go?” he said. “They had power in 1965. They voted against the Voting Rights Act, they voted against the Civil Rights Act, they were still here in 1970 and 1975 and 1980. And there was never a time when people said, ‘Oh, you know that thing about segregation forever? Oh, we were wrong. We made a mistake. That was not good.’ They never said that. And it just shifted. So they stopped saying ‘Segregation forever,’ and they said, ‘Lock them up and throw away the key.’ ”

That dark view of American history may explain a passage in “Just Mercy,” in which Stevenson describes a failed attempt to stop the 2009 execution of a forty-nine-year-old client named Jimmy Dill, who had severe mental impairments. He had wounded a man during a botched drug deal in 1988. Months later, as the victim was recovering, his wife, who had been caring for him, left him, and his health deteriorated. He eventually died, and Dill was resentenced for murder. Dill’s mental impairments might well have entitled him to a reprieve from the death penalty, but he couldn’t afford lawyers, and missed various procedural deadlines for appeals. When Stevenson took the case, a few weeks before the execution, it was too late. “After working for more than twenty-five years,” Stevenson wrote, “I understood that I don’t do what I do because it’s required or necessary or important. I don’t do it because I have no choice. I do what I do because I’m broken, too.”

The family of Stevenson’s mother, Alice Golden, like that of millions of other African-Americans, took part in the Great Migration from the rural South to the urban North in the early twentieth century. They went from Virginia to Philadelphia, where Alice was born. She later reversed the customary trajectory when she married Howard Stevenson, in 1957, and went south with him, a little more than a hundred miles, to his home town of Milton, in rural Delaware. They had three children: Howard, Bryan, and Christy.

“You have to understand that there are two Delawares,” Howard Stevenson told me. “The north, around Wilmington, is basically part of the North, but we lived in the south, which was part of the South. It was very rural, very country. We lived basically in the woods, farm country. We lived next door to my uncle and aunt, and he used to slaughter hogs.”

Their mother never forgot her roots in Philadelphia. “She didn’t want us to grow up with a southern-Delaware frame of mind,” Howard said. “She did all she could to make sure we never forgot the rest of the world. There were places around us with no running water, so Philly was the gateway to the rest of the world.” Alice Stevenson placed a heavy emphasis on education; Christmas presents were microscopes, not footballs. She also had strong views on racial equality. “Some of the black folks in southern Delaware were much more deferential in the face of white people,” Howard said. “Her style was different. She didn’t believe in accepting any kind of racism.” Once, when Bryan was in first grade, she wrote a letter to the town newspaper calling for the integration of the local public schools. Another time, a few years later, she protested when the town’s public-health officers asked the black children to stand at the back of the line to receive their polio vaccines. “She made such an issue of it that for a moment we weren’t sure if they’d even give us our shots,” Bryan recalls.

In the sixties, when the Stevenson children were growing up, the neighborhoods, schools, and swimming pools of southern Delaware were all segregated, in fact if not by law. “There was never a time you could get the majority of people in Alabama or Mississippi, or even southern Delaware, to vote to end segregation,” Bryan told me. “What changed things was the rule of law, the courts. Brown v. Board of Education was ushered in by a movement, but it was a legal decision. And so, for me, I went down the law path, because to be a politician trying to do anti-discrimination work meant you had to work in a handful of communities that were basically majority black.” The jurisdiction of the courts applied everywhere.

Both of Bryan’s parents had long commutes to jobs in the northern part of the state. Alice Stevenson had a civilian post at Dover Air Force Base and became what would later be called an equal-opportunity officer, working to insure that African-Americans received fair housing and education. Howard Stevenson was a lab technician at a General Foods plant in Dover. “We believed that our dad thought he could feed us completely based on what he snuck home from G.F.,” Bryan told me. “I’ve avoided Jell-O since I was ten.” The Stevenson children absorbed their mother’s lessons. Howard Stevenson is a professor of urban education and Africana studies at the University of Pennsylvania; Christy, the youngest of the three children, teaches music at an elementary school in Delaware.

Bryan followed Howard to Eastern College, a small Baptist-affiliated school outside Philadelphia, where he majored in history and philosophy. Then he applied to Harvard Law School, which turned out to be a disappointment. “The courses seemed esoteric and disconnected from the race and poverty issues that had motivated me to consider the law in the first place,” he wrote in his memoir. But as a second-year student, in December, 1983, he took a monthlong internship at what was then called the Southern Prisoners Defense Committee, in Atlanta. Stephen Bright, the organization’s leader, happened to be on the same flight to Atlanta as Stevenson. “By the time the plane landed, we were very close,” Bright recalled. “Bryan had found his calling.” He joined the group after graduating, in 1985, replicating his mother’s migration south—which worried members of the family. “When I heard he was going on his own down there, I almost fainted,” Fred Bailey, Stevenson’s cousin and a retired Philadelphia police detective, said. “Bryan’s a humble guy and a spiritual guy, and he sees the good in everyone. But he knew no one. And he had no family down there.”

Bright’s group did death-penalty and prisoners’-rights litigation in a hostile region and era. “We were the dance band on the Titanic, this very small group of eight or nine people trying to hold back this tide of executions in the old Confederacy,” Bright said. The lawyers divided up the region, and Stevenson, more or less by happenstance, was assigned the cases in Alabama. He showed an aptitude for death-penalty litigation, which is both emotionally taxing and technically demanding. Capital cases have a complex choreography, involving multiple courts in state and federal jurisdictions, all with their own deadlines, rituals, and rules. Lawyers’ mistakes can prove fatal.

The crime rate rose in the late eighties and early nineties, and the few death-penalty lawyers in the South became overwhelmed. In response, a group of lawyers and judges persuaded Congress to fund several state-based death-penalty defense organizations, called resource centers. In 1989, Stevenson, who was still in his late twenties, was appointed to run the Alabama operation. When Republicans took control of Congress after the 1994 midterm elections, one of their first acts was to eliminate funding for the resource centers. Stevenson turned the Alabama resource center into a nonprofit, the Equal Justice Initiative, which survived largely because he was awarded a MacArthur grant the following year, and he used the cash, about three hundred thousand dollars, to keep the organization afloat.

In time, Stevenson achieved a measure of economic stability for E.J.I., thanks mostly to grants from various foundations and a yearly fund-raiser in Manhattan. (With an annual operating budget of six million dollars, the organization now employs seventeen full-time attorneys and twelve legal fellows, young lawyers who spend two years with the group.) “We were having success in overturning these convictions that are wrongful, but it became clear that race was the big burden,” Stevenson told me. “By 2006 or 2007, I had begun to realize that we were going to have to get outside the courts and create a different narrative about race, race consciousness, racial bias, and discrimination in history before we can go back into the courts and expect the courts to do the things that they did sixty years ago, or to create the kind of environment where we could actually win.”

Around this time, Stevenson began studying Alabama history. He didn’t have to look far to find it. The E.J.I. warehouse is on Commerce Street, in Montgomery; the original commerce conducted there was in enslaved people. E.J.I.’s offices stand at nearly the midpoint between the dock on the Alabama River where the human cargo was unloaded and Court Square, which was one of the largest slave-auction sites in the South. Between 1848 and 1860, according to E.J.I.’s research, the Montgomery probate office granted at least a hundred and sixty-four licenses to slave traders operating in the city. Thousands of people were auctioned a few hundred yards from where Stevenson practices law. Slaves awaiting auction were held in chains on the site where E.J.I.’s warehouse was later built.

Montgomery has dozens of cast-iron historical markers celebrating aspects of the Confederate past. Stevenson wanted to put a marker up in front of E.J.I.’s door, to point out the presence of the slave trade. “We went to the Historical Commission and said, ‘How do you get a marker up?’ ” Stevenson recalled. He was told that if he provided accurate information the commission would erect a marker. E.J.I. put together a sixty-page proposal for three markers commemorating the slave trade. Norwood Kerr, of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, e-mailed E.J.I. in response:

I have considered your request for the Alabama Historical Association to support the placement of three historical markers relating to the city’s slave trade. While your scholarship appears accurate . . . I do not think it is in the best interests of the Association to sponsor the markers given the potential for controversy.

“It’s not a huge role, but it is Shakespeare. I get to ask the king if he wants bottled or tap.”

For several years, Stevenson has taught part time at the New York University School of Law, but he doesn’t have his own apartment in the city. He lives on his N.Y.U. earnings and takes no salary from E.J.I. His personal style is nearly ascetic. He has never married. Keeping a promise that he made to his grandmother when he was a teen-ager, he has never let a drop of alcohol pass his lips. (Alcoholism plagued his family.) For years, he lived in a series of small apartments in Montgomery, until he decided to renew his commitment to the piano, which he once played semi-professionally in jazz groups. He decided to buy a piano, then a house, but rarely finds time to play. E.J.I. has no development staff, so Stevenson must raise the six-million-dollar budget virtually alone. Between fund-raising and court appearances, he travels incessantly. Before one of my visits to Montgomery, he had been on planes for twelve consecutive days; before another, seven days.

He has cultivated a network of supporters around the country. In the E.J.I. break room, a state-of-the-art Starbucks machine dispenses free coffee. Since lawyers tend to work late, it gets a lot of use. “This machine has saved lives,” Sia Sanneh, a senior attorney for E.J.I., told me. Howard Schultz, the chief executive of Starbucks, said, “Just by coincidence, two people sent me Bryan’s book at the same time, and I read it in two or three sittings. I was so moved by his story and his selfless acts, and his humanitarianism, that I reached out and called him cold.” They arranged to meet in New York, and then Schultz and his wife visited E.J.I. in Montgomery. “We all meet interesting people, and some of the people don’t live up to their press,” Schultz said. “Bryan is one of the rare individuals who exceed your expectations.” Schultz arranged for “Just Mercy” to be displayed at Starbucks counters for a month; some forty-five thousand copies were sold. Schultz also donated the coffee machine.

The world of public-service lawyering can be competitive and petty, even among ideological allies, but Stevenson’s colleagues speak of him with something close to awe. “Bryan is absolutely in a class of his own,” Chris Stone, the president of George Soros’s Open Society Foundations, which has funded E.J.I., said. “He is a modest, straightforward, ordinary person, and yet he is magical. He is a gift to this country and to a cause that would not be the same without him.” Darren Walker, the president of the Ford Foundation, said, “Bryan is one of the transformational leaders of my generation. He is one of the great prophetic voices of our era.” Barry Scheck, the co-founder of the Innocence Project, said, “Bryan is without question the most inspirational lawyer of our times, not just because he’s charismatic, and also a brilliant litigator, but because he connects emotionally with people like no one else.” Anthony Romero, the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union, said, “Most of us who do this kind of work are good. He’s head and shoulders above us all. He’s a genius. He’s our Moses.”

For all the ties he has forged around the nation, Stevenson is at this point an Alabaman. He knows where to find the pressure points in the local system, a knowledge that he put to good use after the Alabama Historical Association rejected his petition. He enlisted a small organization devoted to African-American history in Alabama as an alternative sponsor. In 2013, E.J.I., with its new ally, was allowed to put up three markers in downtown Montgomery.

During the controversy, Stevenson visited the University of Texas Law School, in Austin, for a conference on the relationship between the death penalty and lynching. Jordan Steiker, the professor who convened the meeting, told me, “In one sense, the death penalty is clearly a substitute for lynching. One of the main justifications for the use of the death penalty, especially in the South, was that it served to avoid lynching. The number of people executed rises tremendously at the end of the lynching era. And there’s still incredible overlap between places that had lynching and places that continue to use the death penalty.” Drawing on the work of such noted legal scholars as David Garland and Franklin Zimring, Steiker and his sister Carol, a professor at Harvard Law School, have written a forthcoming book, “Courting Death: The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment,” which explores the links between lynching and state-sponsored executions. The Steikers write, “The practice of lynching constituted ‘a form of unofficial capital punishment’ that in its heyday was even more common than the official kind.”

Lynchings, which took the form of hangings, shootings, beatings, and other acts of murder, were often public events, urged on by thousands, but by the nineteen-thirties the behavior of the crowds had begun to draw criticism in the North. “The only reason lynchings stopped in the American South was that the spectacle of the crowds cheering these murders was becoming problematic,” Stevenson told me. “Local law enforcement was powerless to stop the mob, even if it wanted to. So people in the North started to say that the federal government needed to send in federal troops to protect black people from these acts of terror. No one in power in the South wanted that—so they moved the lynchings indoors, in the form of executions. They guaranteed swift, sure, certain death after the trial, rather than before the trial.”

In 2007, Sherrilyn Ifill, the president and director-counsel of the N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense Fund, published “On the Courthouse Lawn,” which focussed on two lynchings in Maryland. “What I learned is that an alarming number of lynchings took place not in secret, in the woods, but in public, on the beautiful lawns that are still there in all these communities,” Ifill told me. “And there is nothing to commemorate these lynchings on those lawns, which are in the center of every town in the South.” Lynchings were often covered in local newspapers, and sometimes even previewed in them, and these records were indispensable resources for the E.J.I. researchers.

The staffers at E.J.I., in addition to their legal duties, attempted to identify every lynching that took place in twelve states. They found records for about four thousand lynchings, roughly eight hundred more than in previous counts. Stevenson became convinced that lynching had a historical and a contemporary relevance that needed to be more visible. At first, he imagined erecting more historical markers, but he soon expanded his plan. “One factor, to be honest, was that we started talking about a memorial for 9/11 victims within five years,” he said. “It’s not as if we haven’t waited long enough to begin the process of a memorial for lynching. So that’s when it became clear to me that, in addition to the markers, we needed to be talking about a space, a bigger, deeper, richer space. The markers will give you a little snapshot, but we need to tell the whole story.”

On a steamy Saturday morning in May, about a hundred volunteers assembled at the warehouse. Stevenson commands a stage without being especially commanding. He’s of average height, with a shaved head—a concession to encroaching baldness—and he has the politician’s gift for making his set pieces sound as if he were delivering them for the first time.

“The dog ate my magnetic insoles.”

JULY 5, 1999

“I continue to believe that we’re not free in this country, that we’re not free at birth by a history of racial injustice,” he told a diverse group of students, retirees, local activists, and supporters from around the country. “And there are spaces that are occupied by the legacy of that history that weigh on us. We talk a lot about freedom. We talk a lot about equality. We talk a lot about justice. But we’re not free. There are shadows that follow us.”

His cadence alternates between preachy intensity and lawyerly restraint. As Henry Louis Gates, Jr., the Harvard professor, put it, “There are two different streams of rhetoric in the African-American tradition, the sacred and the secular. Martin Luther King didn’t sound like Thurgood Marshall. You can’t argue in court like you’re preaching in the Abyssinian Baptist Church. But scholars like Cornel West and Michael Eric Dyson in recent years have drawn from both traditions. Bryan does, too.”

Stevenson told the group, “If you’d come to Montgomery a few years ago, you’d find a city with more than fifty markers or monuments to the Confederacy but hardly a word about slavery. And it’s not like in the South we don’t want to talk about the past. We love talking about the past.” He noted that Alabama still observes Confederate Memorial Day (the last Monday in April) and Jefferson Davis’s birthday (celebrated on the first Monday in June). In lieu of a separate Martin Luther King, Jr., Day, the state celebrates a joint Martin Luther King, Jr.–Robert E. Lee holiday. He also pointed out that the two largest high schools in Montgomery are Robert E. Lee High and Jefferson Davis High. “Both overwhelmingly black.”

The group had gathered to participate in Stevenson’s project to commemorate the history of lynching. “Lynching was racial terrorism,” he said. “Old people of color come up to me sometimes and say, ‘Mr. Stevenson, I get so angry when I hear someone on TV talking about how they’re dealing with domestic terrorism for the first time in our nation’s history after 9/11. You need to make them stop saying that, because that’s not true.’ People who had endured lynchings and bombings and threats had a tremendous shape on our lives. We haven’t done a very good job of understanding the legacy of lynching, but the black people that are in Cleveland and Chicago and Detroit and Los Angeles and Oakland and Boston and Minneapolis did not go to those communities merely as immigrants looking for new economic opportunities. They went to those communities as refugees and exiles from the American South.”

After Stevenson’s speech, the volunteers headed out in small teams to fill gallon-size glass jugs with soil from the sites of the three hundred and sixty-three lynchings that E.J.I. had documented in Alabama. Many of the sites are approximate, and the soil project, which has been going on for about a year, is meant to be symbolic rather than scientific. Along the back wall of the room where Stevenson was speaking were about a hundred jugs already filled with soil. The colors of the soil samples varied, from nearly black, in the Black Belt communities across the middle of the state (which was named for its rich soil as well as for its ethnic composition), to the tan, sandy soil from the Gulf Coast, around Mobile. The names of the victims and the dates of their deaths, which ranged from 1877 to 1950, are marked on the jugs.

The soil-collection project is part of a plan to erect the first national memorial to lynching victims, to be built on six acres of vacant land in downtown Montgomery. The project will cost twenty million dollars, and will include a museum at E.J.I. headquarters. It will transform the look, and perhaps the reputation, of Montgomery. A key part of the plan is a dare to the communities in which the lynchings took place. “We’re going to name thousands of people who were the victims of lynchings,” Stevenson told the group before they received their trowels and jars. “We’re going to create a space where you can walk and spend time and go through that represents these lynchings. But, more than that, we’re going to challenge every county in this country where a lynching took place to come and claim a memorial piece—and to erect it in their county.”

Montgomery offers the project a rich civil-rights history and low-priced real estate. For the most part, the streets of downtown are quiet, and the sidewalks are empty. (There is no Starbucks.) Stevenson was able to assemble six and a half acres of contiguous abandoned lots that were once the site of a failed public-housing complex, for about six hundred thousand dollars. It’s a fifteen-minute walk from the warehouse, and up a small hill above the Greyhound bus station where the Freedom Riders were assaulted in 1961.

From a distance, the lynching memorial, designed by Michael Murphy and a team from the mass Design Group, of Boston, will look like a long, low colonnade. Once visitors enter the structure and follow the path downhill, they will see that the columns are hanging in the air, as if from trees. Each column is six feet tall. The current plans call for the soil collected by volunteers to be used in coloring their exteriors. There will be eight hundred and one columns, one for each county and state in which a lynching took place. The names of the victims and the dates of the lynchings will be inscribed on the columns.

The memorial also has a more provocative component. Adjacent to the colonnade will be another eight hundred and one columns, exact duplicates. Each county in which a lynching took place will be invited to remove its memorial column and display it in its own community. The columns that remain in Montgomery will stand in mute rebuke to the places that refuse to acknowledge their history of lynching. “For us, it’s the kind of activism that has clarity, purpose, and a goal,” Stevenson told me. “Sometimes the goals aren’t very clear or very well articulated, and you don’t know whether you’re getting closer or not. This will give us a way of measuring that. We’ll know the places that are resisting, and it should build pressure on those communities, and the people in those communities, that are either not doing enough or need to do more.”

“Pop-Pop’s in the Cloud now, sweetheart.”

AUGUST 13, 2012

The city of Montgomery has come to embrace Stevenson’s plans, in the name of economic development. Mayor Todd Strange told me last spring, “We certainly appreciate the fact that it’s going to lead to a big influx of people who want to come and gain some understanding. Those are good, clean tourist dollars.” But he was also aware that, as he put it, “history is a battleground.” Stevenson has been cautious about unveiling the project, which recently completed the zoning-approval process. Plans for the memorial had been mentioned only briefly in the Advertiser, the local daily. Strange told me, “Bryan has wanted it quiet. We still today have not made an announcement relative to the museum and the memorial park.” For the moment, Stevenson has given the project the generic name of the Memorial for Peace and Justice, which provides no clue that it’s all about lynching.

The reaction of Dick Brewbaker, a Republican state senator who represents a district in Montgomery, may presage a less warm welcome. Brewbaker, who is a prominent auto dealer, was not aware of the project when I asked him about it. “If he wants to do it, he needs to do it with private funds,” Brewbaker said. (Stevenson has used no government funds.) Brewbaker went on, “Why is racially motivated violence worse than any other kind of violence? I don’t give a damn what the motive of the offender was if an act of violence was committed. Interjecting even more race talk into Alabama’s politics is not productive.” Brewbaker noted that Montgomery has several museums about the civil-rights era, including one devoted to Rosa Parks, another to the Freedom Riders, and a third to the movement as a whole (at the Southern Poverty Law Center). “I’d say the imbalance has been corrected pretty quickly, especially when you consider the Confederate symbols that have been removed.” In 2015, Governor Robert Bentley ordered the removal of Confederate battle flags from the grounds of the Capitol. The flags are gone, but the plaques that described them remain.

Stevenson’s first round of fund-raising for the memorial and the museum has garnered a two-million-dollar commitment from the Ford Foundation and a million dollars from the charitable arm of Google; he has also earned more than a million from his book, the sale of movie rights, and his relentless speechmaking. That still leaves a considerable gap for a twenty-million-dollar undertaking, which Stevenson hopes, optimistically, will open in 2017. For the moment, he bears the financial burden himself. Darren Walker, of the Ford Foundation, told me, “One of the things I’ve wanted to do is help Bryan situate his institution in a way that is durable and resilient and not so reliant on him as a charismatic leader.” To that end, the Foundation has given E.J.I. a grant to hire a professional development staff.

I wondered how someone who was successfully juggling so many responsibilities could describe himself as “broken.” Stevenson told me about the moment when he was talking to his client Jimmy Dill, just before Dill was executed, in 2009. “I’ve been in that setting before, but there was something different about this, because the man had this speech impediment,” Stevenson said. “He couldn’t get the words out, and he was going to use the last few minutes of his life—his last struggle was going to be devoted to saying to me, ‘Thank you’ and ‘I love you for what you’re trying to do.’ I think that’s what got to me in a way that few things had. And I, for the first time in my career, just thought, Is there an emotional cost, is there some toll connected to being proximate to all this suffering? I think that’s when I realized that my motivation to help condemned people—it’s not like I’m some whole person trying to help the broken people that I see along the road. I think I am broken by the injustice that I see.”

After Stevenson spoke at the warehouse on that Saturday morning this spring, a fiftyish volunteer named Susan Enzweiler, who had recently retired from a job in historic preservation, received an assignment to visit the site of the lynching of a man named Ebb Calhoun. He died on April 29, 1907, in the village of Pittsview, on Alabama’s border with Georgia. According to the materials provided by E.J.I., on the day before the attack Calhoun’s son reportedly walked between a white man and his daughter on the street, brushing against the woman. The white man, a “prominent merchant,” according to a contemporary report, shoved the son to the ground; the man was already “annoyed by the boisterousness of a large crowd of negroes” in the town that day. E.J.I. gave the approximate address for the lynching as 88 Le Conte Street, in what was described as the central business district of Pittsview.

When Enzweiler and I arrived in Pittsview, we found what appeared to be the shell of a business district. A convenience store and a one-room post office survived, but the structure at what might have been 88 Le Conte was a crumbling brick building. Enzweiler studied the arrangement of the bricks. When bricks were more fragile and less standardized than they are today, builders would alternate “stretchers” (bricks laid lengthwise) with “headers” (bricks with the short side exposed). There were headers every six rows in the building, which Enzweiler took to mean that it was constructed around the beginning of the twentieth century. It had probably been standing at the time of the lynching.

As Enzweiler was looking around, a woman drove up to the post office, across the street. She was a letter carrier. She said that her route covered Pittsview and the neighboring town of Cottonton. “Pittsview is majority black and minority white,” she said. “Cottonton is the opposite.” She said that the residents on Le Conte where Enzweiler was standing were all white; the residents farther up the block, on the other side of a traffic light, were all black. The road of demarcation between the racial enclaves was called Prudence.

Stevenson had asked the volunteers to try to imagine the events that led to the lynchings. Ebb Calhoun had returned the next day to the site of his son’s confrontation. Several white men, including the merchant who had had the altercation with the son, harassed Ebb and then accused him of firing a shot at a visitor from Columbus. A group of whites assembled, surrounded Calhoun, and then shot him dead. “This was the main drag. They executed him in a public place,” Enzweiler said. “Mr. Calhoun must have known what was going to happen. He was trying to protect his son, taking the hit that was probably meant for him. Ebb was a hero.” She took out her trowel, bent over to brush away pieces of crumbled brick, and began to fill her glass jar with soil.

Jeffrey Toobin has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1993 and the senior legal analyst for CNN since 2002. This article appears in other versions of the August 22, 2016, issue, with the headline “Justice Delayed.”

See additional sources:

Bryan Stevenson and the Legacy of Lynching