Young boy standing in front of police officers at a blockade. North Avenue, West Baltimore. April 28, 2015. Credit Devin Allen

Sarah Lewis discusses the special issue of Aperture magazine she edited, devoted to photography of the black experience.

By Sandra Stevenson June 27, 2016

Sarah Lewis studies photography and its power to shape ideas of race and identity with a depth few others can match. Before joining the faculty at Harvard, where she is an assistant professor of history of art and architecture and African and African-American studies, she held curatorial positions at the Museum of Modern Art and the Tate Modern, where she often shaped provocative exhibitions dealing with race, representation and other topics.

Her most recent work is even more accessible, conversational and bold — guest-editing Aperture’s special issue devoted to the photography of the black experience.

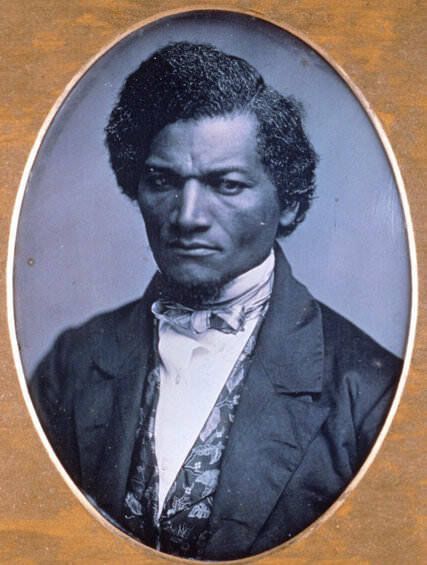

With a curator’s eye, she laid out images old and new, from portraits of Frederick Douglass to the Brooklyn street scenes of Radcliffe Roye. With a writer’s ear, she commissioned essays, conversations and insights that pulled together powerful black voices, including Wynton Marsalis, Ava DuVernay, Teju Cole, Margo Jefferson and Henry Louis Gates Jr.

She titled the issue Vision & Justice (which is also the name of her course at Harvard), and in the worlds of both art and media, it has caused a stir. Fans of the hefty edition have been calling it a vital corrective to the persistent white gaze of elite photography, although Ms. Lewis prefers to describe it as simply a fully rounded portrait of black life.

“People are just getting their copies of Aperture and it’s exploding with love,” she said.

An exhibit tied to the issue will open in August at Harvard.

Ms. Lewis, 36, soft-spoken and quick to smile, came to The Times earlier this month to discuss the power and influence of imagery, especially as it relates to race, and why we all need to become more visually literate.

The interview below is a condensed and lightly edited version of a conversation that went on for hours at The Times, then continued via email.

Sarah Lewis at The Times to discuss her work on Aperture’s Vision & Justice issue. Credit George Etheredge/The New York Times

As a picture editor at The New York Times, I think a lot about authenticity. I grew up in Wyoming, with very few people of color, so when my mother saw them in the paper, she’d say, “Why is it that we’re just like these black blobs with eyes and teeth?” It would drive her crazy. And then on my father’s side, they were from central Louisiana, and every time we would visit my grandmother, she would have portraits and photos from back in the 1800s of family members. That’s what drew me to photography. What drew you to photography?

There are almost too many personal stories and anecdotes I have in mind to isolate just one. Actually, there is — there was one formative moment for me as a child that made me think about the gravitas of images connected to how we see race in America.

We had a flood in my house growing up. I was maybe single digits, 8 or 9. And we had to move out of the house. We came home and it was just flooded. And our neighbor next door — we lived in an entirely white neighborhood and we built it — came by to help. And she was just struck still and stopped at the entryway, she didn’t come in, not because of the water, but because she was shocked to see these photographs we had of my great-great-grandparents. And I’ll never forget what she said: “I don’t even have any pictures of my great-great-grandparents.”

And it occurred to me a) that these were unique; b) that there was significance to having a visual record in the form of a photograph of African-Americans in that time period. And it made me want to explore the history and understand that.

Additionally, Deborah Willis’s landmark book, “Black Photographers 1840-1940: An Illustrated Bio-Bibliography,” was in my childhood home. That was the book that made me interested in the relationship between race and photography. It sat alongside our own family pictures in the living room table for years. As an only child, I would spend hours just poring over it. As you can imagine, the fact that Deborah Willis is now a colleague and mentor is incredibly meaningful to me.

Untitled. 2010. Credit Deborah Willis

How has your interest in photography evolved?

It’s moved from simply interest in it as a documentary enterprise to something that I think has resonance for civic engagement, for broader-level conversation than you have only in the art world. It goes far beyond that.

So what did you think when Aperture contacted you to curate an issue on the black experience?

I was honored, but I knew it was going to require a great deal of work and so I was also slightly daunted.

The request was to guest-edit an issue on the theme of photography and African-American life. With the Obama presidency ending being sort of an animated reason for doing the issue.

This is an institution that has created some landmark qualifications for good photography, but most of those photographers are not of color.

Can one issue, I asked myself, ever offer a corrective move for that history, and the answer is no. So I was daunted because I knew that to do this issue would become about more than doing one issue. It would mean an engagement with the institution and by proxy many other institutions where you need to ask pertinent questions about the dearth of engagement with this topic.

But I did it gladly, with a lot of joy. I think one of the things I would emphasize, though, from the start is, I made clear to the team that I worked with, and they were completely on board with this, that I wanted honor and dignity to permeate every interaction with every artist and every writer and every poet and scholar we communicated with, because of the enormity and gravitas of the topic.

How did you select the artists that are featured in Vision & Justice?

My aim for this issue of Aperture and selecting the theme of vision and justice was to create an issue that would have writers, photographers, poets, scholars, whose level of mastery and gravitas on work matched the weight of this topic. Nevertheless, that means there are many emerging photographers in here, many younger scholars and writers.

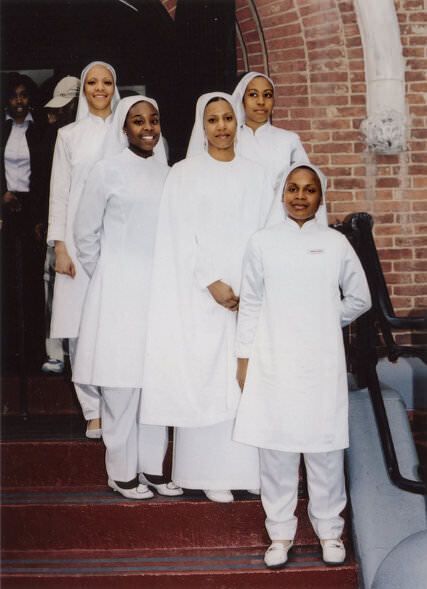

Muslim girls’ training and general civilization class. Harlem. 2010. Credit Jamel Shabazz

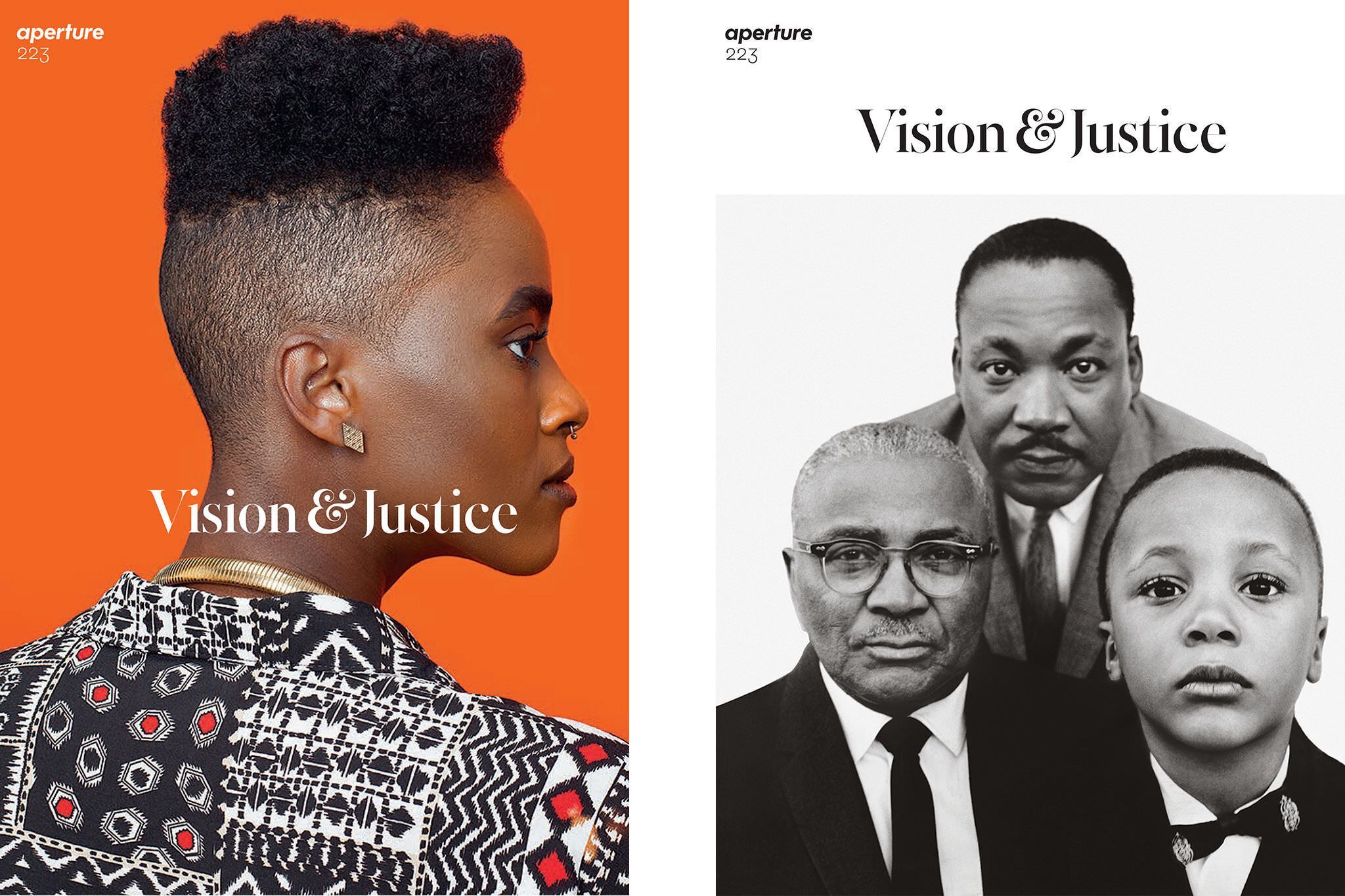

Why two different covers?

I wanted to have two contrasting covers — one by Richard Avedon of Martin Luther King Jr., his father and son, and another portrait by the young photographer Awol Erizku from the Afropunk 2014 festival — to underscore both the historic nature and raw vitality of this topic of vision and justice.

For an issue with such a chronological sweep, no one image would do.

The magazine starts with Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s meditations on Frederick Douglass’s speeches about photography and concludes with the portfolios by emerging and established photographers from LaToya Ruby Frazier, Dawoud Bey, Deana Lawson and a column by Studio Museum in Harlem director Thelma Golden. It took months to figure out what would make for just the right thematic cover image, and I feel they are stunning — synoptic and strong — but I would have loved to have even more. If printing had been free, 20 covers would have been nice.

I particularly love the cover with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., his father and son. I had no idea this photo existed.

I think one out of, say, 20 people — and I’m saying scholars, art historians, that I know — knew of this image before I showed it to them.

Avedon so masterfully composed this image. He’s made King hover above both the past and the present, with his father and son; because of the framing of his shoulders, he’s almost angelic, almost depersonalized, de—disembodied somehow. But you still see, because of the features, how connected he is with the past and the future.

Ah, but that gaze is I think what hits me, and it emblematizes the importance of vision for justice. I decided to title the issue Vision & Justice, not Photographs & Justice or Images & Justice, because it has to do with this, with the impact of how images get us to see the world differently.

Is there a particular photo in the collection that you’re willing to say is your favorite?

I will say I selected every image. I went back to photographers’ studios often to get the image I knew was really there. So my hand — my fingerprint is on every single page.

Oluchi, Katouché, Adia, Noémie, Kadra, Kara Young, Cynthia Bailey, Tyra Banks, Liya, Beverly Johnson, Gail O’Neill, Karen Alexander, Shakara, Clara Benjamin, Naomi Campbell and Iman. New York City. 2000. Credit Annie Leibovitz

I think people might be surprised that Annie Leibovitz is in here. When I saw a photograph of black supermodels all dressed in black and gathered by Iman that Annie Leibovitz took in 2001, I tore it out of Vanity Fair magazine and taped it right up on my wall.

I was living in the U.K. right after college; I moved four times in the subsequent four years. I took it with me each time. What struck me was the exquisite grace of these models in the aggregate and how the picture served as a corrective model, a demonstration of the force of photography for representational justice. For any stereotype about a black female identity, power, self-possession or beauty, Annie Leibovitz’s composition of these women, models who have mastered the art of physical gesture to convey an idea in a glance, offered a sharp retort, a collective dare.

Susan Rice. New York City. 2009. Credit Annie Leibovitz

I felt just as moved by her picture of Susan Rice, who emblematizes a new association of race and power by sitting at the center of the U.N. table as the United States ambassador with effortless poise and preparedness, pencil in one hand on the desk, the other hand coolly draped toward the viewer resting on the chair as if the world is her audience, because it is. Of course, when I was asked to guest-edit the issue and I chose the theme of Vision & Justice, these gesturally strong images by Annie Leibovitz had to make it in.

Why do you say that people were surprised that Annie Leibovitz was included in the issue?

I think the issue doesn’t only have photographers of color, because well, there’s Annie Leibovitz and Sally Mann and various scholars who are not African-American. And that’s for a reason, because this has been a collective project.

But Annie was a surprise for some people, not to me. Some of the most epiphanic images we have of black life have come from her lens; her mind and heart. And so I thought she was crucial to have in this issue, because when she’s also engaging with her subjects, she’s mindful silently of the place that that image will occupy in history.

When she came to photograph me, her studio had combed online to find every image possible. They presented them to me and said, how do you like yourself best? How do you want to present yourself?

And that’s striking and again, mindful of the continuum. It was such an honor for me, not just because it’s an incredibly inventive innovative photographer, but because of the other African-Americans, and the few African-Americans who’ve been in front of her.

I thought she was crucial to this discussion. Yeah, so she’s in there. And Sally Mann’s series. I think it’s important to curate into the pages and that was the portfolio that brought me to tears as I tried to edit it down, to I think 10 pictures. Because she was able to, using that sort of that wet plate coating process, her 8-by-10 camera, she was able to condense at times 150 years of quite painful history onto a single image.

Untitled. 2006-15. Credit Sally Mann/Gagosian Gallery

Let’s talk a little more about black ownership. When I worked at the Black Filmmaker Foundation, one of the criteria was it can’t be a black film unless it’s directed by a person of color.

I’m interested less in what qualifies something as black photography, black art, black cinema, as I am in seeing what comes of agency on the part of black artists. I’m interested in seeing what comes out of their heart and mind and soul, with regard to the medium that they choose.

The entire reason why this project is important, I think, is because we are investing a level of care in how we portray the full spectrum of humanity, right? That’s why this is important, it’s how do we honor human life.

And so of course, we are robbed of the viewpoints we need when we don’t have photographers of color increasingly having their images disseminated by incredible newspapers like The New York Times, or any other outlet.

But it seems like a particularly rich period for black artists. What are your thoughts about the state of black art and artists, such as Kehinde Wiley, for example?

The legendary art historian Robert Farris Thompson once said, “Until you know how African you are, you will never know how American you are.” Well, yes. Indeed. As a culture, we’ve begun to recognize what Bob has long been saying with his work. This is part of why it is a particularly rich time for black expressive culture and will remain. In the U.S., we now know that when we celebrate black culture, we are celebrating American culture. When we honor the pioneering work of artists like Carrie Mae Weems, Romare Bearden, Kehinde Wiley, Jamel Shabazz or Lorna Simpson, extol the poetry by Elizabeth Alexander or Claudia Rankine, the music by Jason Moran or scholarship on black artists by Richard Powell or Deborah Willis, we are celebrating our collective heritage.

Untitled (Eating lobster). 1990. Credit Carrie Mae Weems

What are your views on fine art photography versus photojournalism?

There are, perhaps, a different set of concerns for photojournalists — how to create a synoptic narrative captured in a glance — and there are different considerations about audience. But what does it mean that a project that began as photojournalism can end up being seen as so-called fine art photography over time? Consider the work of Gordon Parks, for example, whose photojournalism informed his filmmaking and more. While photographic history has long been split in the way that you describe, I don’t think of the categories as oppositional. Particularly as the media landscape shifts, the distinction is one that I find less and less useful.

Do you think changes in technology have made it easier for photographers of color to be seen and recognized, or has it made it harder?

I think what we’re looking at now is the democratization of photography. Everyone has access. Well no, not everyone — many people have access to be able to create an image. But what that also requires is an increased state of vision literacy on the part of viewers.

For me it shines a spotlight on the artist and the photographers who are so proficient at getting us to concentrate and isolate and look at what’s in front of us.

Colours. 2014. Credit Radcliffe Roye

How do you think representation of race has changed over time, especially as we’ve become more of a transnational multicultural society?

I think the main trend line or shift that’s occurred as it relates to race and photography and representation in photography is that you see a move from photography as a corrective enterprise, you know, to photography as a way to celebrate the complexity of human life. Of black life.

By corrective, I mean you really have to go back to the 19th century and talk about the development of race representation in photography because of the way in which racial science attempted to use photography as a mode to show the inhumanity of African-Americans, and all the work that was being done — the counter-archive that black photographers in the antebellum period and the Civil War period created to offer a corrective for that.

Frederick Douglass, by Samuel J. Miller. 1847-52. Credit Chicago Art Institute

Again, that’s why [Frederick] Douglass was in front of the camera. It was to create this counter-archive, to — as Skip Gates would put it — stem the Niagara flow of stereotypes that had become a mass glut at that period.

So it moved from this corrective period to a more celebratory mode; I think Jamel Shabazz is a great exponent of this, with his honor and dignity series really chronicling black life that might be just quotidian to those people but isn’t given its due lots of times because of saturation we have of images that show one denigrating cultural narrative about African-Americans.

I think resisting essentialism when it comes to black aesthetics is very important, period.

I think part of the reason why we’re robbed of perspectives when we don’t see the full range of black expression is because there is no one prescriptive way to live this life with black skin.

And how do you think these images can engage in a broader dialogue about class and politics and gender?

Photography doesn’t have to try to engage with a broader dialogue about class and race and gender because it does whether we know it or not.

Internally we are like picture galleries, right? I mean, Ava DuVernay says this too, that we have these mental images we walk around with. And we engage with each other through these inner pictures, these inner images, that are created and fashioned out of the argot of pictures we’ve seen of others, throughout our lifetime, right?

So it doesn’t — there’s nothing we need to do, I think, because photographs, the impact of photographs, do this to us. The question I think for any platform, any newspaper, any journal, any magazine, is to recognize the weight of — and the impact of — the images that you put in front of readers, and attempt to show the broadest possible scope of humanity, unbound, you know, through them.

Sarah Lewis, right, curator of Aperture’s Vision & Justice issue, discussing her work with Sandra Stevenson, a picture editor for the Times, in New York City. Credit George Etheredge/The New York Times

So then how do you rate us, as far as the newspaper industry? Going back to my original comment I do — as a woman of color — feel that weight.

Absolutely. No, I have so much respect for the responsibility that you take on yourself with this work. And I think you’re doing an incredible job. I think it’s difficult to find an image that creates a sense of that synoptic capture or of a narrative. It’s difficult work. Especially when you are faced with what I would call image glut, right, saturation.

I think this work that you do is so vital for civic dialogue. We’re living in this increasingly polarized climate in society, where we tend to live amongst people who vote the way we do, have religious beliefs that are like ours, oftentimes of the same race. And what that means is that the way we process worlds unlike our own comes down to the media we see, and the pictures that we consume.

That’s what puts the onus on this work, today more than ever. It is similar to what happened at the very beginning of photography when it seemed as if it saturated the environment. But what we have now that’s different is that the polarization puts more responsibility on those pictures to tell hard truths.

Sandra Stevenson has been a picture editor at The New York Times for more than a decade.

A version of this article appears in print on June 28, 2016, on page C1 of the New York edition with the headline: Countering a White Gaze. Today's Paper

See original article at:

Sarah Lewis Aperture Vision Justice Celebrating Black Culture