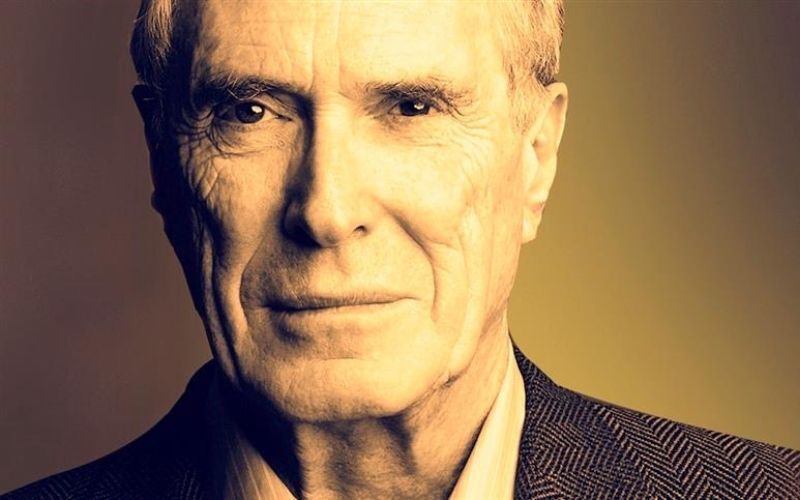

Pulitzer-Winning Poet Mark Strand on the Heartbeat of Creative Work and the Artist's Task to Bear Witness to the Universe

by Maria Popova

It’s such a lucky accident, having been born, that we’re almost obliged to pay attention.

In the 1996 treasure Creativity: The Psychology of Discovery and Invention — the same invaluable trove of insight that demonstrated why “psychological androgyny” is essential to creative genius and gave us Madeleine L’Engle on creativity, hope, and how to get unstuck — pioneering psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi interviewed 91 prominent artists, writers, scientists, and other luminaries, seeking to uncover the common tangents of the creative experience at its highest potentiality. Among the interviewees was the poet Mark Strand (April 11, 1934–November 29, 2014) — a writer of uncommon flair for the intersection of mind, spirit and language, who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize and a MacArthur “genius” fellowship, and served as poet laureate of the United States.

For Strand, Csikszentmihalyi writes, “the poet’s responsibility to be a witness, a recorder of experience, is part of the broader responsibility we all have for keeping the universe ordered through our consciousness.” He quotes the poet’s own reflection — which calls to mind Rilke’s — on how our sense of mortality, our awareness that we are a cosmic accident, fuels most creative work:

We’re only here for a short while. And I think it’s such a lucky accident, having been born, that we’re almost obliged to pay attention. In some ways, this is getting far afield. I mean, we are — as far as we know — the only part of the universe that’s self-conscious. We could even be the universe’s form of consciousness. We might have come along so that the universe could look at itself. I don’t know that, but we’re made of the same stuff that stars are made of, or that floats around in space. But we’re combined in such a way that we can describe what it’s like to be alive, to be witnesses. Most of our experience is that of being a witness. We see and hear and smell other things. I think being alive is responding.

But that response is not a coolly calculated, rational one. Echoing Mary Oliver’s memorable assertion that “attention without feeling … is only a report,” Strand describes the immersive, time-melting state of “flow” that Csikszentmihalyi himself had coined several years earlier — the intense psychoemotional surrender that the creative act of paying attention requires:

[When] you’re right in the work, you lose your sense of time, you’re completely enraptured, you’re completely caught up in what you’re doing, and you’re sort of swayed by the possibilities you see in this work. If that becomes too powerful, then you get up, because the excitement is too great. You can’t continue to work or continue to see the end of the work because you’re jumping ahead of yourself all the time. The idea is to be so… so saturated with it that there’s no future or past, it’s just an extended present in which you’re, uh, making meaning. And dismantling meaning, and remaking it. Without undue regard for the words you’re using. It’s meaning carried to a high order. It’s not just essential communication, daily communication; it’s a total communication. When you’re working on something and you’re working well, you have the feeling that there’s no other way of saying what you’re saying.

Echoing Chuck Close’s notion that the artist is a problem-finder rather than a problem-solver — a quality recent research has emphasized as essential to success in any domain — Csikszentmihalyi adds:

The theme of the poem emerges in the writing, as one word suggests another, one image calls another into being. This is the problem-finding process that is typical of creative work in the arts as well as the sciences.

Illustration by Julie Paschkis from 'Pablo Neruda: Poet of the People.'

Strand speaks to this himself:

One of the amazing things about what I do is you don’t know when you’re going to be hit with an idea, you don’t know where it comes from. I think it has to do with language. Writers are people who have greater receptivity to language, and I think that they will see something in a phrase, or even in a word, that allows them to change it or improve what was there before. I have no idea where things come from. It’s a great mystery to me, but then so many things are. I don’t know why I’m me, I don’t know why I do the things I do. I don’t even know whether my writing is a way of figuring it out. I think that it’s inevitable, you learn more about yourself the more you write, but that’s not the purpose of writing. I don’t write to find out more about myself. I write because it amuses me.

Like T.S. Eliot, who championed the importance of idea-incubation, Strand considers the inner workings of what we call creative intuition, or what Virginia Woolf called the “wave in the mind”:

I am always thinking in the back of my mind, there’s something always going on back there. I am always working, even if it’s sort of unconsciously, even though I’m carrying on conversations with people and doing other things, somewhere in the back of my mind I’m writing, mulling over. And another part of my mind is reviewing what I’ve done.

And yet too much surrender to this pull of the unconscious, Csikszentmihalyi cautions, can lead to a “mental meltdown that occurs when he gets too deeply involved with the writing of a poem.” He cites the practical antidotes Strand has developed:

To avoid blowing a fuse, he has developed a variety of rituals to distract himself: playing a few hands of solitaire, taking the dog for a walk, running “meaningless errands,” going to the kitchen to have a snack. Driving is an especially useful respite, because it forces him to concentrate on the road and thus relieves his mind from the burden of thought. Afterward, refreshed by the interval, he can return to work with a clearer mind.

Driving, coincidentally or not, is also something Joan Didion memorably extolled as a potent form of self-transcendence, and rhythmical movement in general is something many creators — including Twain, Goethe, Mozart, and Kelvin — have found stimulating. But perhaps most important is the general notion of short deliberate distractions from creative work — something more recent research has confirmed as the key to creative productivity.

Csikszentmihalyi crystallizes Strand’s creative process, with its osmotic balance of openness and structure, reveals about the optimal heartbeat of creative work:

Strand’s modus operandi seems to consist of a constant alternation between a highly concentrated critical assessment and a relaxed, receptive, nonjudgmental openness to experience. His attention coils and uncoils, its focus sharpens and softens, like the systolic and diastolic beat of the heart. It is out of this dynamic change of perspective that a good new work arises. Without openness the poet might miss the significant experience. But once the experience registers in his consciousness, he needs the focused, critical approach to transform it into a vivid verbal image that communicates its essence to the reader.

Csikszentmihalyi points out another necessary duality of creative work that Strand embodies:

Like most creative people, he does not take himself too seriously… But that does not mean that he takes his vocation lightly; in fact, his views of poetry are as serious as any. His writing grows out of the condition of mortality: Birth, love, and death are the stalks onto which his verse is grafted. To say anything new about these eternal themes he must do a lot of watching, a lot of reading, a lot of thinking. Strand sees his main skill as just paying attention to the textures and rhythms of life, being receptive to the multifaceted, constantly changing yet ever recurring stream of experiences. The secret of saying something new is to be patient. If one reacts too quickly, it is likely that the reaction will be superficial, a cliché.

In a sentiment that calls to mind one of Paul Goodman’s nine kinds of silence — “the fertile silence of awareness, pasturing the soul, whence emerge new thoughts” — Strand himself offers the simple, if not easy, secret of saying something new and meaningful:

Keep your eyes and ears open, and your mouth shut. For as long as possible.

Csikszentmihalyi’s Creativity remains a must-read and features enduring insights on the psychology of discovery and invention from such luminaries as astronomer Vera Rubin, poet Denise Levertov, sociobiologist E.O. Wilson, social scientist John Gardner, and science writer Stephen Jay Gould.

For more of Strand’s genius in the wild, treat yourself to his sublime Collected Poems (public library), released a few weeks before his death.

The opening piece in the collection, which is one of my all-time favorite poems, offers a remembrance particularly befitting in the context of Strand’s lifelong serenade to mortality:

When the Vacation is Over for Good

It will be strange

Knowing at last it couldn’t go on forever,

The certain voice telling us over and over

That nothing would change,

And remembering too,

Because by then it will all be done with, the way

Things were, and how we had wasted time as though

There was nothing to do,

When, in a flash

The weather turned, and the lofty air became

Unbearably heavy, the wind strikingly dumb

And our cities like ash,

And knowing also,

What we never suspected, that it was something like summer

At its most august except that the nights were warmer

And the clouds seemed to glow,

And even then,

Because we will not have changed much, wondering what

Will become of things, and who will be left to do it

All over again,

Source: Brainpickings