by Maria Popova

“For-get-me-not.”

Long before Facebook, young people exchanged musings on life in friendship books (abbreviated, amusingly enough, as FBs) — small booklets or hand-bound pamphlets, also known as poetry albums, which a person would pass around for friends and penpals to fill with verses and inspirational quotes. This shared journal was a kind of primitive cross between Tumblr and Facebook — yet another example of vintage versions of modern social media. In the Netherlands, these booklets were known aspöesiealbums and were especially popular among schoolgirls.

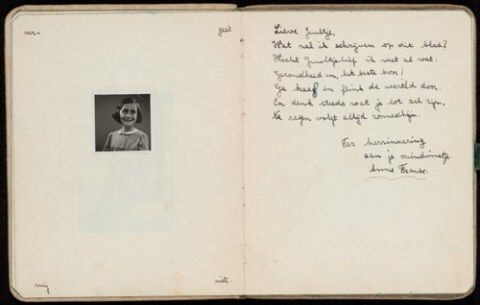

In The Secret Museum (public library) — which also gave us Van Gogh’s never-before-seen sketchbooks and the surprisingly dark story of how the Nobel Prize was born — Molly Oldfield unearths a friendship book entry by none other than Anne Frank, who penned a short verse in her friend Juultje Ketellapper’s poetry album in June of 1939, a couple of weeks after Anne’s tenth birthday.

Anne Frank's entry in Juultje Ketellapper's friendship book

On the third page of the book, Anne glued a photograph of herself, then inscribed each corner of the page with “For-get-me-not.” On page four, she wrote her short poem:

Dear Juultje,

What shall I write here?

Wait, Dear Juul, I have an idea:

Good health and all the best!

Be good be full of zest,

And whatever fate may be divining,

Remember every cloud has a silver lining.

In memory of your friend

Anne Frank

Oldfield ponders:

I could imagine Anne sticking in that photograph herself — that same fun, expressive face, now famous — then carefully writing her words into her friend’s book. Her writing was very neat.

It was a time when Jews were still treated largely on par with Amsterdam’s non-Jewish citizens — a time when it was possible for a child as bright and joyful as Anne to have many friends, both Jewish and not, and to inhabit her childhood with the beautiful buoyancy of trusting the future stretched wide open with hope and promise. The poem is thus at once optimistic and crushingly ominous in its prescience of what that future, so grimly different from her childhood hope, held for Anne.

While it’s hard — morally repugnant, even — to consider anything about Anne’s tragedy a “silver lining,” the closest we get to such consolation is her enduring legacy, preserved thanks to her famous, existentially indispensable diary. In it, with equally heartbreaking prescience, she writes:

You’ve known for a long time that my greatest wish is to be a journalist and, later on, a famous writer.

And if anyone had the right — the desperate urgency — to seek such a “silver lining,” it was Anne’s father, Otto, who was the only surviving member of the family and who honored his daughter’s wish by bringing her diary to life with a wish of his own:

I hope Anne’s book will have an effect on the rest of your life so that, insofar as possible in your own circumstances, you will work for unity and peace.

(Photographs from The Secret Museum, courtesy of Molly Oldfield / Harper Collins)

See original article from source: Anne Frank Friendship Book