When we talk about executive functions, we’re usually talking about distinct, discrete skills that are easy to get our arms around. Empathy, while often lumped in with executive functions, is not a singular skill, but a package of skills that pulls from multiple parts of the brain. Children who are empathetic can form and sustain friendships, are more likely to behave well in class, and are less likely to engage in aggressive, antisocial, or criminal behavior.

What is Empathy?

Empathy is often defined as the ability to identify with the suffering of another. This definition, however, is only partly correct. Human beings have the capacity for three kinds of empathy:

Reflexive Empathy: Every human is born with the ability to respond to the pain of others. When shown images of others in pain, a child will have a neurological response in the area of the brain that controls pain. Researchers have even documented newborn babies crying in response to the distress of other babies. Infants respond far more intensely to the sound of another infant crying than to other unpleasant sounds. The phenomenon of reflexive empathy is thought to be cause by “mirror neurons.” These nerve cells fire whether a child is experiencing something or just witnessing someone else experience it.

Emotional Empathy: This is the vicarious experiencing of another’s emotional pain. Closely related to reflexive empathy, emotional empathy does not require images of pain or sounds of distress to illicit a response. Just knowing what another is going through, is enough to create that second-hand pain response, as it occurs in reflexive empathy.

Cognitive Empathy: The ability to take the perspective of another and accurately imagine that person’s experience. This is the most sophisticated form of empathy and the only one that is definitely linked with helpfulness, kindness and other pro-social behaviors. It’s the type of empathy that translates second-hand suffering into feelings of understanding and caring.

Empathy and the Brain

Understanding the three types of empathy makes it clear that being an “empathetic” person is not a simple personality trait. It’s a package of skills that combines biological non-negotiables of mirror neurons and genes, development of neural pathways, and the executive function of perspective taking.

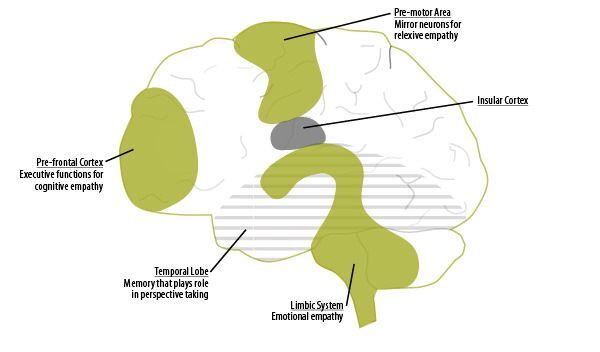

In order for reflexive empathy to build to emotional empathy, the mirror neurons in the premotor area of the brain must develop a strong connection to the limbic system, which processes the emotional aspects of empathy. This connection occurs via neural pathways in the insular cortex.

How does a child experience another’s pain without being overwhelmed by emotional distress? By tapping the power of the prefrontal cortex and its executive function of emotional regulation. This area of the brain also allows a child to engage on a cognitive level, taking the perspective of another and determining which helpful behaviors would be appropriate. Additional circuits are needed to connect to the temporal lobe, where long-term memories are stored, allowing the child to activate past experiences that may be similar to what a friend is experiencing now.

Empathy is a complex suite of skills that builds upon itself. And while reflexive empathy is an inborn trait, it does not automatically lead to the cognitive empathy required to build and sustain meaningful relationships, hold a job, or parent a child effectively.

When Cognitive Empathy doesn’t Emerge

A study conducted in 2009 observed changes in the brains of young men diagnosed with conduct disorder (CD). CD is a precursor to antisocial personality disorder, and a serious psychiatric condition in its own right, often linked with physical aggression, cruelty to animals and bullying.

The young men observed experienced the reflexive empathy of mirror neurons firing – in fact, they experienced it more intensely than control subjects. But this feeling of another’s pain didn’t connect with the emotions and executive function areas in the same way. Instead, there was very little activation in the executive function area observed, indicating that perspective taking and high-level cognitive processing were not taking place. The emotional areas that were most strongly activated in the CD subjects were those closely associated with strong pleasure and powerful negative feelings. These negative emotions may cause a young person with poor executive function and self-regulatory development to lash out, or behave more aggressively, instead of adopting the pro-social behaviors of normally developing children.

So how do we make sure that children are getting the early wiring needed to connect reflexive empathy to healthy emotional and cognitive empathy?

Teaching Empathy

- Meet their needs – Treat the children in your life with empathy. Studies suggest that children are more empathetic when their own emotional needs are being met, they’re securely attached to caring adults, and if they themselves are getting empathetic help with their own problems.

- Lead by example - Modeling cognitive empathy and narrating your thought processes out loud will give them a template that will guide how they process events. Point out situations that call for empathy. When reading a book about a character who is going through a hard time, talk about how that character must be feeling. Ask the child how he would feel in the same position.

- Help them find common ground – Kids are more likely to feel empathy for those who they see as similar to them. Help the children in your life discover what they have in common with others – particularly others with whom they’ve had conflict in the past. The Roots of Empathy program does this by encouraging elementary school aged children to learn about and identify with the feelings of a baby.

- Practice changing roles and perspectives – Ask children to pretend to be someone else in a hard situation. How do they feel in this situation? What would make them feel better? Kids like to pretend, and this is something that can help them practice the executive function of perspective taking. Even the simple act of asking a child, “How would you feel if …?” can diffuse a fight and help the child see things from a different point of view.

- Make faces – One way to get children to take another’s perspective is to ask them to make a face that shows what someone else is feeling. The small motor act required to make a facial expression is enough to cause changes in the brain and body that align with the emotion the child is trying to illustrate.

- Foster a happy environment – The good feelings that come from positive social interactions make children more adept at accurately reading the feelings of others.

- Document prosocial behavior in the classroom – Use photos and stories in periodic debriefings with educators and children. It can help focus teachers and tune them into the empathy-based actions happening around them, as well as give young children an opportunity to reflect on their behavior, thereby reinforcing the habit.

See additional sources at:

Harvard Center for the Developing Child

“The Development of Empathy: How, When and Why,” Nicole M. McDonald and Daniel S. Messinger, University of Miami

“Teaching Empathy: Evidence-based tips for fostering empathy in children” and “Empathy and the Brain” Gwen Dewar, PhD, Parenting Science

“The Visible Empathy of Infants and Toddlers,” Valerie Quann and Caorl Anne Wien, Young Children, July 2006