Great Lakes fishers tend to operate small, family-owned businesses. GreatLakesPhotography.

A big lift of whitefish out of Lake Superior weighs about 2,000 pounds; but for Dennis VanLandschoot, the president of the fifth-generation family fishing business in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, only about half of that will generate any income. After removing the scales, head, stomach and bones, all that is left is the fillet. VanLandschoot sends the remains to be turned into fertilizer. Other fishermen send their leftover fish parts to be used for animal feed or to a landfill, where they need to pay 20 cents a pound or more to dispose of the waste.

While VanLandschoot takes comfort in knowing that spare.parts of his catch are being used, he still has a thousand pounds of waste that creates no income, and he says, “But you also have to ask, ‘What do we do to honor the fish?’”

Recently an option has emerged, aiming to create a sustainable supply chain for these neglected Great Lakes fish parts. Organized by an intergovernmental organization, the 100% Great Lakes Fish Initiative seeks to utilize every part of the fish pulled from the five water bodies, creating a more sustainable industry and helping develop the region’s rural economies.

The initiative was born out of a layover that David Naftzger, the executive director of the organization, had in Iceland. With available free time on his work trip, he set up a meeting with the Iceland Ocean Cluster. This group helped spearhead what has become an industry success story for sustainability and economic recovery following the introduction of strict limits to prevent collapse of the Atlantic cod fisheries in the 1990s. Aimed at helping create a more sustainable fishery and helping one of the country’s largest industries rebound, the new limits instituted by the Icelandic government greatly reduced the amount of fish the fishing fleet is allowed to catch.

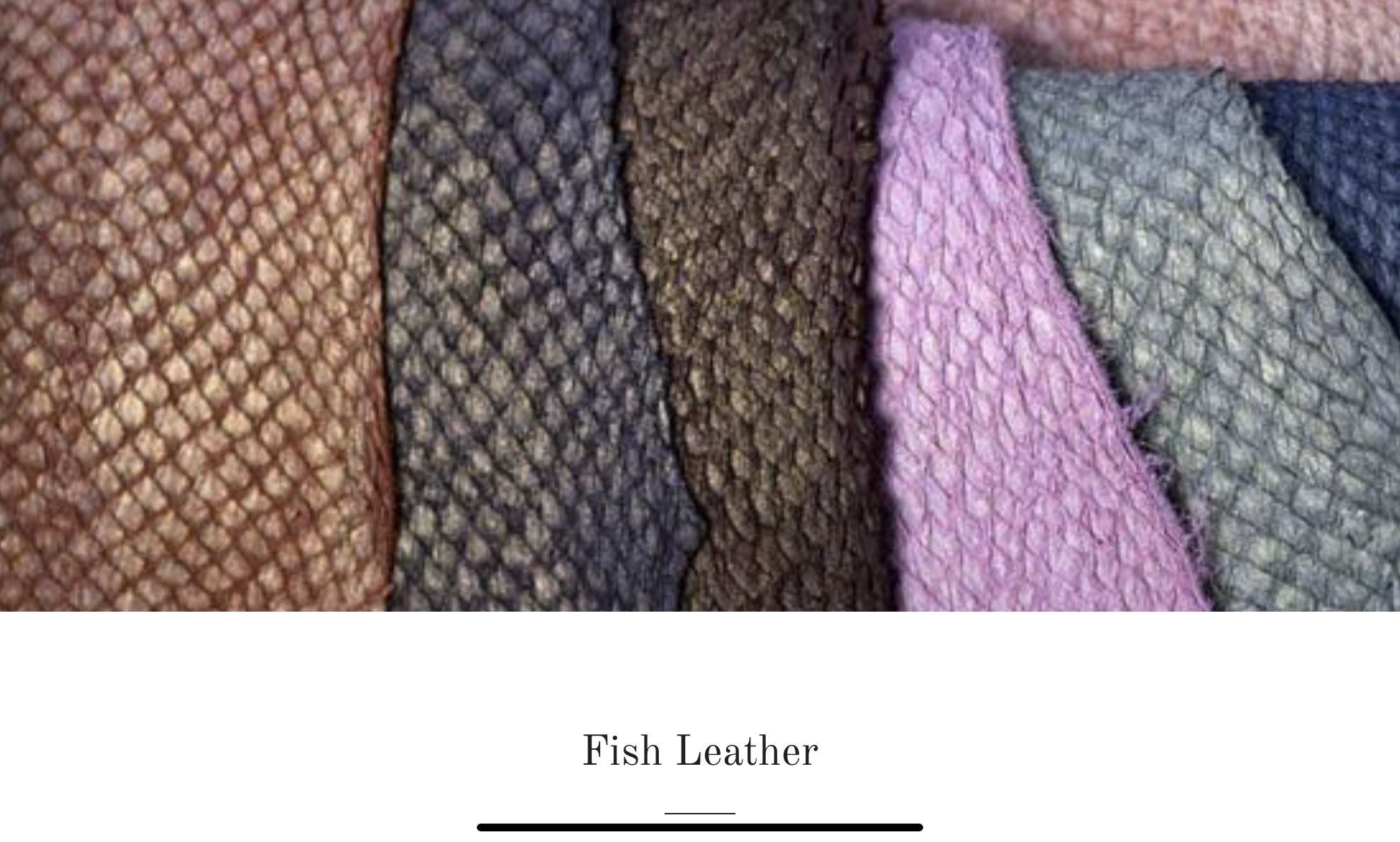

The fishing industry initiative started very simple, drying the fish heads and sending them to places like Nigeria, where they’re a common cooking ingredient. The Iceland Ocean Cluster helped reignite an interest in fish skin leather, which many coastal communities had made historically. Since then, brands like Gucci and Nike have used the very strong, thin and durable leather in their products.Great

Today, gelatin and collagen are extracted from the fish and are often used in cosmetics and health supplements, To date, Icelandic fisheries use about 90 percent of the fish they catch, creating a 30-fold increase in the use of the fishery’s byproducts.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, the commercial Great Lakes fishery has declined precipitously for decades. “There’s two things that go hand in hand. “One is the decline in the number of commercial fishermen, and a lot of that has been exacerbated because of environmental changes we’ve faced,” said Charlie Henriksen, owner of Henriksen Fisheries in Door County, Wisconsin, and chair of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources’ Lake Michigan Commercial Fishing Board

“Also invasive species have worked in tandem with pollution, climate change and historic overfishing to wreak havoc on the lake ecosystem. Today, commercial fishermen on the lake still operate on narrow margins.”

Much like Iceland’s Atlantic cod fishery 30 years ago, the Great Lakes fish economy is largely reliant on fish fillets, Naftzger said. Working with colleagues in Iceland, the 100% Great Lakes Fish Initiative’s goal is to create a similar “value pyramid” structure for Great Lakes fish products.

Companies who sign onto the “100% Great Lakes Fish Pledge” aim to use the entirety of each fish they catch or raise by the end of 2025. To date, five aquaculture and 30 commercial fishing companies have signed on, representing approximately 90 percent of commercial fish production in the region.

“For now, the goal is to eliminate landfilling in Great Lakes fisheries,” Naftzger said. “Getting more companies to convert fish parts to fertilizer or compost would reduce costs and greenhouse gas emissions.”

But once that’s achieved, Naftzger wants to help these fishermen move on to more lucrative options for what’s now considered waste. The goal is to take the fish economy Iceland developed and apply those practices to the Great Lakes. Much like in Iceland, there are opportunities to derive medicines, supplements, leather and cosmetic ingredients from Great Lakes fish.

A research lab in Iceland performed a series of tests where they deconstructed a number of commonly caught Great Lakes fish species and analyzed the different compounds in each one. The group is also looking at species like the white sucker, which is a common bycatch, meaning they’re caught unintentionally.

Many Great Lakes fish have promising fat and oil content, which could be turned into fish meal, oil and protein hydrolysates (chopped up proteins used in nutritional supplements and medicines). Partners have created prototypes of the first collagen made from whitefish, protein hydrolysates from walleye heads and leather from a number of species.

The greatest challenge with the region is the sheer size. Unlike Iceland, which is an island with a very centralized fish industry, the Great Lakes region is massive, and the fishers tend to operate small, family-owned businesses.

Naftzger wants to connect with companies already in the region who produce collagen from cows and pigs, but could also expand to fish. He also aims to look at other markets across the world and smaller ones at home. A company in Minnesota, called Fiskur Leather, makes artisan products from fish leather. These smaller, artisanal productions could be a good option on tribal reservations where resources are limited.

Some fishermen have also gotten creative on their own. Whitefish livers and trout cheeks have found their way onto shelves and restaurant plates in northern Wisconsin. While Henriksen’s signature product is a whitefish fillet, over the years he’s made fish sausage and dog treats, and he recently began saving his fish skins to be turned into leather. VanLandschoot sends some eggs to a producer who turns them into caviar.

While the goal is to generate more products and income from these fish parts as quickly as possible, Naftzger believes that by the end of the year much of the fish will at least be turned into compost or fertilizer, eliminating the need for landfilling. In addition to more research and analysis, he’s also planning a virtual fish tanning workshop and plans to help fishers of the region connect with other companies that could use their fish parts.

Henriksen is cautiously optimistic about the future of the project. Last year, he made about $2.50 for a pound of his fish. New products that add $2 or $3 to that total would make a big difference.

For VanLandschoot, his mission is always to honor the fish he catches, along with his family’s 100-year-old business. He hopes that finding opportunities to turn those fish into additional products will allow him to continue that tradition in an increasingly unstable lake.