A Radical Compassion

by Barbara Kaufmann

How the Sikh Temple massacre ignited a prayer, an unholy alliance and an extraordinary mission.

“When someone tells you something, sometimes you respond with ‘what?’ not because you didn’t hear what was said, but because you can’t bear what was said. The instant disbelief is as involuntary as a hiccup because your brain can’t comprehend it. You think maybe if you ask the question again, the stalling, another breath and a quick reset will bring you a different answer.”

That was the second time on August 5, 2012 that something involuntarily stalled Pardeep Kaleka on his way to temple. The first time was when his daughter in the car with him, confessed a few blocks from home that she had left her notebook behind. Pardeep, the ever vigilant father had asked a question that would prove fateful: “have you brought your Sunday School assignments along?” Grumbling and chastising her for being careless, he turned the car around to go back for the notebook. The delay was just long enough to cheat a fate that may have been holding an even greater tragedy and loss for Pardeep that day.

Pardeep, (“Par” to friends,) a man with soft, deep brown eyes, and an easy manner speaks in a voice that’s gentle but articulate and strikingly steadfast. His youthful unlined face veils experience far beyond his years and his sense of humor and heart-centered charisma reaches out an invisible palm to embrace an audience listening to his story about a day that would change his life forever.

On his way to the temple that Sunday morning, he noticed a string of official vehicles and police cars whizzing past him at high speeds; it appeared that multiple jurisdictions were responding to something major. A former police officer in a tough neighborhood known as “Little Beirut” on the north side of Milwaukee, Kaleka knew that kind of response meant a huge incident that is live and very serious. (Terrry, Don, 2013) As he rounded the corner to approach the access street to the temple, he was stopped by an officer blocking the route.

“I’m sorry sir; we can’t allow you into that area.”

“But I am trying to get to our temple; what is going on?”

“There’s been an incident at the temple. We have shots fired. And the area is not secured.”

This is where Pardeep asks that ‘what?’ rhetorical question.

As the police officer begins to repeat himself, Par’s phone rings and he hears his mother’s voice telling him there is gunfire in the temple and she is hiding in a closet. His father’s phone calls him moments later but it’s not his father’s voice on the line; it’s the temple priest who tells Par to call for help because his father has been wounded. Pardeep Kaleka’s mother and father are in a temple that is now under assault. He looks over at his daughter sitting in the car next to him and can’t find words to tell her anything in the moment. He remembers his earlier irritation about the notebook. Tears well in his eyes. In the parking lot, he squats and prays.

The First Annual "World Heritage Day" celebration

In the aftermath, Pardeep finds out that his father, the temple president, could have fled through any door, but instead was making a sweep of the temple escorting members to exits when he encountered the shooter. Armed with a small knife, the elder Kaelka was no match as he struggled with the gunman and was mortally wounded by a stranger determined to murder those he’d never met but had learned, at a distance, to hate. Satwant Kaleka’s last word that day as he faced his killer was “Waheguru” the Sikh name for “God.”

Listening to Par tell his father’s story, I am reminded of Gandhi. They say the last word Gandhi uttered as he glimpsed his assassin coming toward him gun in hand, was “Rama,” an Indian mantra for “God.” (Lindley, 2010) Perhaps this is what men of deep faith do; their devotion conjures prayer even in their last words. Their acts of compassion are prayers. Many martyrs of faiths faced death with a holy name on their lips. Perhaps their last words are prayers because their lives are prayers.

The shooter at the Sikh Temple in Oak Creek on that August morning was a male white supremacist who after killing 6 and leaving one in a vegetative state, and then wounded by an officer, turned his gun on himself. He had emptied 8 or 9 rounds into the first officer he encountered on the scene before even entering the temple. Lieutenant Brian Murphy miraculously survived. The F.B.I. and President Obama called the mass killing domestic terror and a hate crime. The shooter was ex-military, ex Psy-ops and had ties to several white supremacist groups including metal Neo-Nazi bands. (Elias, 2012) He also had geographical ties to Littleton Colorado near where the incidents of Columbine High School and the Aurora theater massacre took place. The weapon he used that day was a semi-automatic hand gun purchased legally in Wisconsin along with multiple magazines that hold 19 rounds each. (CNN, 2013)

How is it people at such opposite poles of philosophy and faith meet in such extreme ways? Sikhs are gentle people who practice a kind of faith that includes something I understand and can only describe as “radical forgiveness” with an equally “radical compassion.” Ironically, white supremacists see the world rather as an ongoing and terrifying holy war.

How do people come to their philosophies? How has mass killing and gun violence with its incident after incident of hatred acted out upon strangers, people of faith and even children, now become a norm in our society? When did the life of one human being become so unimportant, so expendable? How has the value of life itself come to mean so little? What value can be assigned to a singular life when organized violence and military killing “accidentally” becomes simply, “collateral damage?” The Pentagon name for this collateral damage is “Bugsplat.” (Koehler)

Pardeep doesn’t believe the theory that this mass killing was a case of mistaken identity where Sikhs were possibly mistaken for Muslims. The shooter was radicalized in the army, was a Psy-Ops operative (Psychological Operations) and recruited others to the “cause.” (SPLC, Winter 2012)

Instead, he thinks the killer was motivated by something else:

“I believe what he was attacking is the same thing that a lot of Americans are uncomfortable with—CHANGE. This is why I think this was not just a Sikh Tragedy; it’s more an American Tragedy. America was built on the principals of Change from its birth. You can approach this from a variety of faiths; many religious leaders have described this tragedy as the faith based 9-11.

“It’s the commonality of people that binds us together and allows us to recognize the humanity of others. Religious principles also have lots of commonalty, no matter the religion. However, as in “humanity,” we have been trained to overlook the commonalities and magnify the differences and that is totally contradictory to what we need to be doing to build compassionate communities. In Sikhism there are many examples of radical compassion, and no other Guru has exemplified this as well as the originator of the faith, Guru Nanak, and no other concept exemplifies this better than the belief of “Chardi Kala.”

Chardi Kala, as I have learned, is a steadfast state of optimism and joy that is embraced because of an acceptance, an even exuberant kind of contentment that forms and informs life in Sikhism. Those of the faith consider all to be the will of God—even times of adversity and things that are painful. It’s a faith that all is God and since God is in all things, everything is therefore, ordained and holy. God being omniscient and omnipresent is the cosmic force driving all life and Chardi Kala is to hold absolute faith in the intelligence of that force. To gaze at another human in Sikhism is to say ‘hello’ to God.

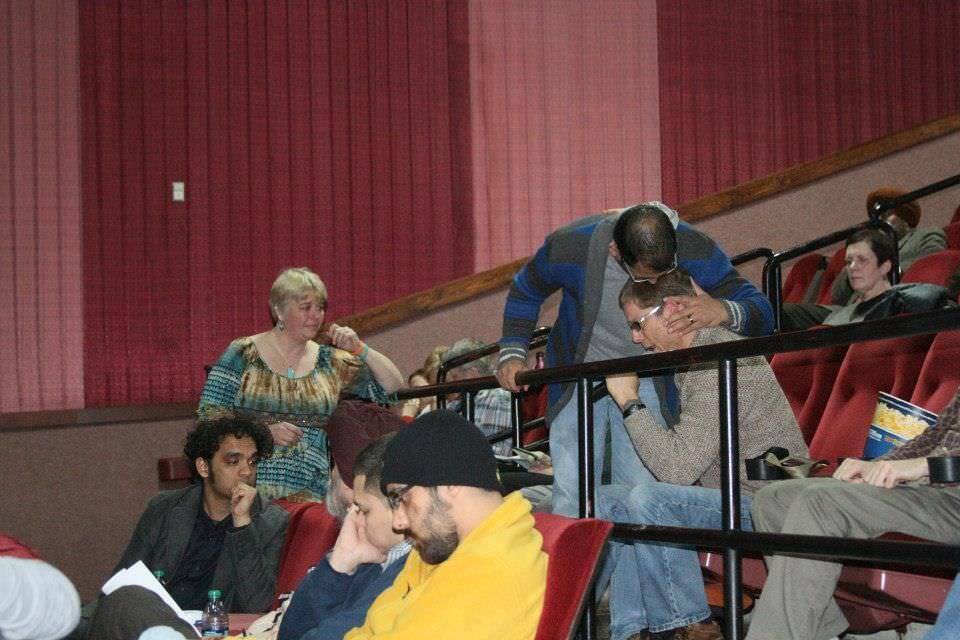

The photo of Pardeep comforting Arno was taken during a presentation of a screening of short films by Sharat Raju and Valarie Kaur about the August 5 massacre and the Sikh experience in the U.S. After the film there were some speakers and then the floor was opened.

Arno took the mic to talk about his experience from August 5 and broke down crying, Par came and rescued him.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, instead of seeking justice or revenge, or turning away from the world in isolationism, a religious fraternity turned to questions: “what is our responsibility in the cause of tragedy; what might best serve healing, preventing violence and compassionate change?" Realizing that their faith was mysterious to many, their grief was conscripted into reaching out to the community with more interaction and education about Sikhs and Sikhism.

Post racial America is a myth. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, since America elected a black president, a thousand more hate groups have organized. (Potok, 2011) Black hip hop artist and DC community activist Head-Roc puts it this way:

“It’s important to hold space for change. Skin color and hatred has a long history. You don’t change 500 years of hatred and indoctrination overnight. Don’t lose your hope and don’t be cynical. You do what you can. You do your part in your lifetime. The problem isn’t that black life doesn’t matter or minority life doesn’t matter; it’s that life itself doesn’t mean enough. And the attitude goes way beyond race or creed or color. When you treat people as property without human rights, you treat the planet as property and trample humans’ rights to it.” (Kaufmann, 2013)

Inflammatory and marginalizing language has been used as recruitment tools, propaganda, to mark shared “outsider” status, to reinforce or pass on prejudices and to hurl insults at people considered different, undesirable, deficient, inferior, non-privileged or lacking in some way. Language can be subtle or “loud” as an instrument of leverage and has been used as a device to separate humans from their humanity throughout history. It has found its way into literature, media, legend, the arts, story, the stories of griots, to justify genocide and slavery, and in the twentieth century, it was manipulated particularly and deliberately in the language of tabloid journalism, and most recently and glaringly in the late 20th and early 21st century in music lyrics. It is used regularly by white supremacist bands to stir emotions and recruit marginalized youth into the movement. Language is the primary weaponry of prejudice. (Schaffer, 2012)

In his grief, Pardeep’s ‘why’ questions echoed as he wrestled with his post trauma and the existential crisis that arises when one tries to make sense of something that, in a world where human suffering is inevitable, volitionally adds more violence, more hatred, more misery. He began looking for answers in the unfathomable. Did it all come down to skin pigment? How does that make sense; how is that humanly sane on a planet where humans come in so many colors? In a humanity that didn’t choose or change, but was created with that inherent diversity?

An agency called Against Violent Extremism (AVE, 2013) told Pardeep about someone who might be able to answer some of his deep and troubling ‘why’ questions. They steered him in the direction of Arno Michaelis, a reformed white supremacist.

Arno Michaelis

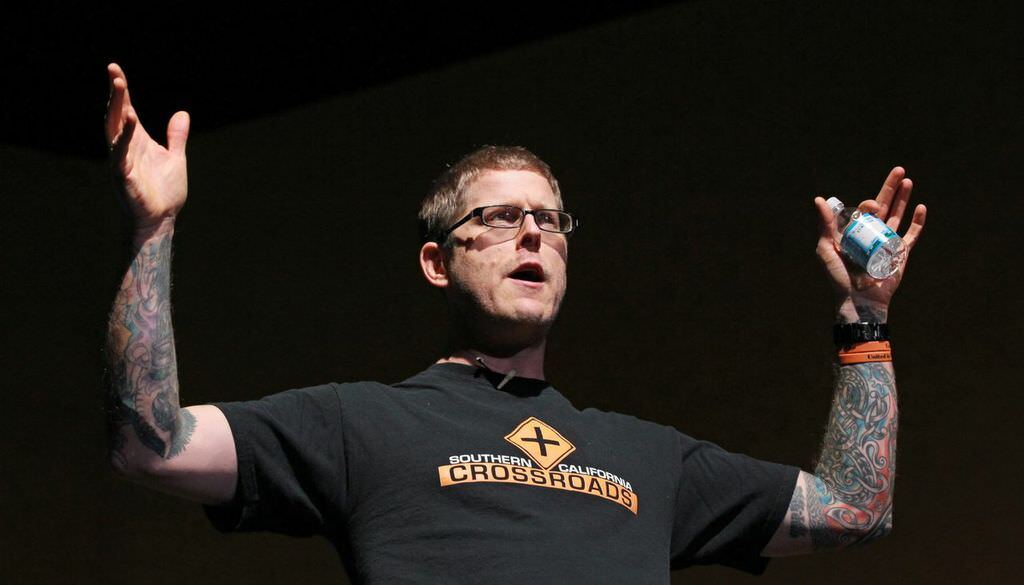

Arno Michaelis, upon first meeting, is a 6 foot hulk of tattoos and intimidation with sandpaper skin and a raspy voice that startles with its deep and booming timbre. His presence alone fills the whole room. A Skinhead in his past life, he looks every bit the part except for the ever so slight twinkle in his eyes and hint of smile at the corners of his mouth, those likely returned to him about the same time as his soul. He cuts a dragoon and looming figure until he begins speaking of his daughter; a reference to her melts his full six feet into a giant puddle of teddy bear.

Michaelis has an unlikely defender and benefactor in Pardeep Kaleka:

“You have to know this guy, know his true heart, his real self-- Arno walks down the street plugging expired meters for strangers.”

As Michaelis tells his story, his humanness and vulnerability grow exponentially. He is direct, brutally honest, remorseful and yes, likeable. The audience eyes the pair glancing back and forth trying to connect the incredulous dots and reconcile such an unlikely pair and their almost palpable affection for each other. They don’t just appear together, do speaking engagements together and work together with at risk youth, but they are brothers in every nuance of the word. They are a visual oxymoron; what initially appears an unholy alliance reveals itself to be a deep spiritual bond.

This “odd couple” co-founded an organization and work with an arresting courage and conviction that life may make more sense and may become more revered if something can be salvaged from an extremist horror. Their illustrated dedication and determination leads one to wonder if their meeting was karmic and perhaps manipulated by divine design.

Each man paced inside his own brain and fretted and sweated in apprehension and fear before their first meeting that would prove life changing for both. Par wondered if Arno was truly reformed as he calculated that it would be nightfall by the time their meeting ended in a neighborhood that would then be dark and unfamiliar.

Arno winced at the anticipated anger and judgment in the greeting he’d receive because of his past as a Neo Nazi and Skinhead, especially by a man whose father was killed by someone whose identity he once embodied. Acutely aware that his history can’t be erased, Arno is still haunted by the things he did in his former life. Each man wrestled with their own imaginations, questions, self-doubts, trepidation, shame, angst and insecurities. Par felt that he had sorely neglected his soul before the events of August 5 and Arno still deals with the fallout of a past lifestyle he now considers soul-less.

Arno’s book My Life After Hate, a brutally honest catharsis and raw confession, tells the story of the man he once was. It’s hard to read—never mind imagining how it could have been lived. Arno felt he still had much to atone for and was having trouble assimilating the guilt and the reality that it was tragedy that catapulted him to notoriety and captured the media’s interest. Arno was all too familiar with unholy allegiances. What would come of this uncanny meeting?

Shortly before their summit, Par injured his eye severely in a bizarre home accident and arrived at their planned liaison in bandages, his eye propped open with steri-strips. Not the imposing or angry presence expected, Par looked quite the vulnerable mangled mess. And Arno, ever outspoken and not one to censor his thoughts, blurted out:

“Dude, what happened to your eye?!”

It was one of those moments—that instant of simple shared humanity, of vulnerability, of woundedness—that set the tone for the rest of the meeting and the rest of their lives. In fact, the day would come when Par would tell the weeping six foot tatted mass and mess of human being, that he—Arno, was the answer to his father’s last prayer. Their meeting lasted hours. Later, their cooperative epiphany would have far reaching ripples for others in whose lives they would come to make a difference.

Par, who had to postpone much of his own grief while trying to be strong for his mother and his religious community, was looking for solace, for answers. Par asked and Arno answered the questions Par harbored about the ideology that drives a man to mass murder. He queried about the journey one must take to reach the kind of hatred and insanity that not only took his father from him, but violated the safety of children and the sanctity of a place of worship.

Arno described to Par a kind of allegiance to an identity and a world that closes in on you as it becomes narrower and narrower. He describes a form of recruitment and indoctrination that resembles cult programming.

White Supremacy is based on fear and paranoia fueled by the blending of the races that will likely end in the disappearance of the Caucasian race. It’s an old, old fear in the DNA of America.

“Racism is a kind of slavery; you can’t be a football fan because you believe that the black and white races should not mix. Seinfeld is out because he is Jewish. And violence becomes a cycle where paranoia sets in and much of the world is out to get you; everything is someone else’s fault. It’s a lifetime sentence of pain and fear. The lifestyle cripples your identity and limits your experience of the world.”

Outspoken about every facet of his life and the lessons that it taught him, Arno Michaelis unabashedly shares his story with youth and they hang on his every word because he’s imposing, charismatic, fascinating and authentic. There is no greater credibility than someone who has been there. He understands character, human rights and how life and individuals need to be held in respect and even reverence. That is his new work and his identity now.

About his former life, Michaelis says it was a relief to leave. It was his daughter and single parenting that compelled him to look objectively at his life and lifestyle. An honest look triggered a deep depression that lasted for about a year as he evaluated himself and penned his My Life After Hate opus. A former member of the white power band “Centurion,” Arno had to face and live with the knowledge that his art in the form of music, is still being used to recruit lost and angry youth, particularly disenfranchised males, to the cause—as Skinheads.

Addicted to adrenalin and drama, Arno’s withdrawal from the lifestyle came in stages before he could reclaim his soul for his final chapter. He became part of the Rave scene for a time and went through a dark suicidal depression that a clergy would immediately recognize as a true “dark night of the soul. For both men, it was certain that “the children shall lead them” for Arno’s daughter is the only reason he is alive today. It was Pardeep’s daughter who unwittingly caused his eye accident which elicited a radical compassion from Arno. It was daughters become oracles who led fathers to step up to change the world.

The children are still leading them as they learn from the youth they work with every day. Arno Michaelis and Par Kaleka have formed not just a personal alliance but something greater than the sum of its parts—Serve 2 Unite. Serve 2 Unite is an organization that educates about disparate beliefs, faiths and life experiences and works with at risk youth in the inner city of Milwaukee, Wisconsin as well as kids in the privileged suburbs, sometimes bringing them together. They hold events, present speaking engagements and workshops, and teach youth about disenfranchisement, hatred, violence, gangs, identity and inherent human worth. They teach about taking responsibility for the state of the world, the power of love and yes, radical compassion.

Pardeep and Arno during a school visit

Arno’s book has become a textbook used by schools to prevent violence and gangs and a teacher who sponsored him to speak to her students wrote a manual and teacher’s guide. Par is working on his half of the memoir that will become a book about their unusual alliance and they have piqued the interest of a publisher.

Their organization, Serve 2 Unite (S2U) was actually born on August 5, 2012, they tell me. Arno and Par consider the day of the massacre their founding date and the mission an answer to Pardeep’s father’s last prayer. Working at the grass roots level, that is where they believe change and radical compassion begins.

They begin in schools where they work with students and consult with teachers to examine methodology in schools and consider reforms that eliminate marginalization or foster aggression and are instead holistic, nourishing and empowering for students.

At Serve 2 Unite, they considered the question: What would the ideal school be like?

The answer?

“One in which the interests and curiosities of students are honored, where multiple intelligences are valued, and where the social and emotional, as well as intellectual, needs of children are met. Sadly, however, American society has drifted so far from what our children need and rightfully deserve. There are no Common Core State Standards for the social-emotional needs of children, and due to budget restraints, the arts are minimal at best.

The result? School environments have become more and more toxic and children continue to feel disconnected from their peers, families and schools. Abuse and violence are on the rise and affecting more and more youth throughout our communities. One clear and predominant reason for this is the underuse and under-appreciation of social wellness programs in schools.”

So, Serve2Unite partnered with Arts@Large to pilot a social wellness program in the Milwaukee Public Schools and beyond that will allow students, staff, and parents to create strong communities built upon mutual respect, compassion, and service.

The Chapter includes Pardeep Kaleka, son of Sikh leader Satwant Kaleka killed on Aug. 5th, and Arno Michaelis, former white supremacist. They engage youth and staff in interactive presentations and conversations with global mentors that include Against Violent Extremism, The Forgiveness Project, Over My Shoulder Foundation and uses technology to bring the global mentors into the classroom.

Involved educators and administrators collaborate to recruit teams of diverse and emerging student leaders who will become agents of social change in their school and local communities. Those student leaders identify issues unique to their school communities, and with the guidance of Serve2Unite adult guides, develop an arts-based project aimed at addressing the problems.

Projects are shared with the world in the Serve2Unite digital magazine, which encompasses the responsible use of Social Media.

Chapters hold community and family conversations that recruit and involve community partners like Milwaukee Public Schools Violence Prevention Program that examines violence prevention strategies and builds community through community service and service learning projects.

Serve 2 Unite Magazine plans gallery shows and features for their service-oriented projects designed in collaboration with Arts @ Large and artist educators. A variety of arts are included: the literary arts, visual, multimedia and performance arts and more. Engaging the community and beyond in this way empowers students, builds new skills and shares their message with the world. Some of the projects include street art, wellness explorations, creativity, peace walks, neighborhood gatherings, face paintings, street dances and other projects that engage and empower youth as well as educate.

As for Par and Arno, they go where they are invited and take the stage in schools, libraries, meeting halls, civic organizations and cultural centers to speak about gangs, bullying, diversity, racism, and things that marginalize and empower youth. Their work is now piloted in several Milwaukee area schools with their goal a regional network of diverse interfaith youth leaders to educate about cross-cultural religious awareness and help at-risk communities.

Serve 2 Unite exists to co-create a blueprint for a better world and to bring that world into being—a world where all faiths and people are recognized, respected, and celebrated. How? With a radical kind of compassion.

For more information:

Serve 2 Unite

Contact Pardeep Kaleka

Contact Arno Michaelis

My Life After Hate (Arno Michaelis)

© 2013 by Reverend B. Kaufmann

Called “The spirit behind the Words and Violence Project,” Reverend Kaufmann is an award winning writer, poet, author and artist who founded “Words and Violence,” now in its 3rd edition, a global (140 countries) educational resource of more than 600 pages about bullying in its many forms—from the playground to media. The new edition features a section on performing arts and is hosted at Voices Education Project—humanitarian and pedagogical institute.

Longtime human and civil rights advocate, activist and peacemaker, she has written for Voices Education Project, Huffington Post, magazines, journals, is a founding case author for George Washington University School of Business, and is a script writer and filmmaker. One of the early members of a sister cities project with Russia, she held office for a decade, was impresario for their annual fundraising concert, and wrote a grants for Russian-American partnerships. One grant funded the social infrastructure for decommissioning chemical weapons in Russia with Russian partners and USAID. That story is chronicled in Looking Back, an anthology by authors who lived its history. She is a Charter for Compassion member—both local and global and her “One Wordsmith” website where she “Writes to simply change the world” features humanitarian “story.”

One Wordsmith

Words and Violence Pro

ject at Voices Education

Charter for Compassion

Compassionate Fox Cities

Bibliography

AVE. (2013). Against Violent Extremism. Retrieved from Against Violent Extremism.

CNN. (2013). Wisconsin Sikh Temple Shooting Full Coverage. Retrieved from CNN.

Elias, M. (2012). "Sikh Temple Killer Wade Michael Page Radicalized in Army." Southern Poverty Law Center, Winter Intelligence Report.

Kaufmann, B. (2013, August 29). "What's a Head-Roc?". Retrieved from Voices Education Project "Words and Violence" Program.

Koehler, R. (n.d.). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from Voices Education Project: http://voiceseducation.org/content/project-bugsplat

Lindley, M. (2010). Gandhi's Last Words. Retrieved from Scribd: http://www.scribd.com/doc/42883955/Gandhi-s-last-words-by-his-secratary-Pyarelal-Nayyar

Potok, M. (2011). "The Year in Hate and Extremism: The Patriot Movement Explodes." Southern Poverty Law Center Intelligence Report.

Schaffer, D. a. (2012). "An Overview of the Language of Prejudice. Retrieved from Voices Education Project "Words and Violence". http://voiceseducation.org/content/overview-language-prejudice

SPLC. (Winter 2012). Intelligence Report. Southern Poverty Law Center.

Terrry, Don. (2013, Fall). "The Sikh and the Skinhead." Teaching Tolerance, 24-27.