Viktor Frankl on the Art of Presence as a Lifeboat in Turbulent Times and What Suffering Teaches Us about the Meaning of Life

“When a man finds that it is his destiny to suffer… his unique opportunity lies in the way he bears his burden.”

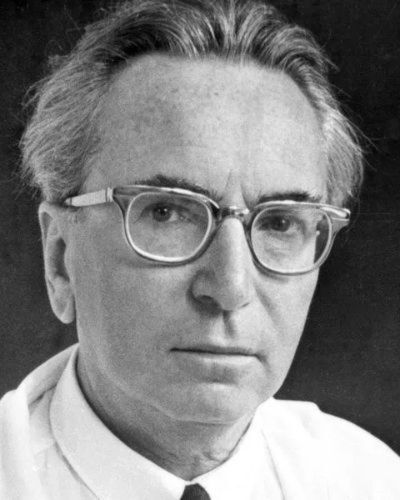

The life-story of Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl, born on March 26, 1905, is one of history’s greatest testaments to the tenacity of the human spirit. In his remarkable 1946 psychological memoir Man’s Search for Meaning (public library), previously discussed at length, Frankl reflects on what his devastating time at Auschwitz taught him about the most essential driver of life — the inextinguishable human hunger for meaning, which separated those who survived from those who perished.

In one particularly poignant passage of the book, Frankl reminds us that the art of presence — an art so central to our everyday well-being— isn’t merely about savoring the pleasant moments of everyday blessedness. Rather, its canvas stretches all the more exquisitely in precisely the opposite circumstances — those most trying and turbulent moments, when the ability to inhabit the present makes all the difference between life and death, both figuratively in matters of the soul and, in Frankl’s Auschwitz experience, literally and bodily:

A man who let himself decline because he could not see any future goal found himself occupied with retrospective thoughts. In a different connection, we have already spoken of the tendency there was to look into the past, to help make the present, with all its horrors, less real. But in robbing the present of its reality there lay a certain danger. It became easy to overlook the opportunities to make something positive of camp life, opportunities which really did exist. Regarding our “provisional existence” as unreal was in itself an important factor in causing the prisoners to lose their hold on life; everything in a way became pointless. Such people forgot that often it is just such an exceptionally difficult external situation which gives man the opportunity to grow spiritually beyond himself. Instead of taking the camp’s difficulties as a test of their inner strength, they did not take their life seriously and despised it as something of no consequence. They preferred to close their eyes and to live in the past. Life for such people became meaningless.

To be sure, Frankl is far from advocating for filtering the present through rose-colored glasses in order to soften its intolerable pain. Quite the opposite — much like John Cage came to believe when he discovered Buddhism, Frankl argues that presence comes from leaning into suffering, not from tensing against it:

When a man finds that it is his destiny to suffer, he will have to accept his suffering as his task; his single and unique task. He will have to acknowledge the fact that even in suffering he is unique and alone in the universe. No one can relieve him of his suffering or suffer in his place. His unique opportunity lies in the way in which he bears his burden.

Frankl points to commitment, be it to human relationships — “the soft bonds of love [which] are indifferent to life and death,” to use Isaac Asimov’s poetic language — or to purposeful work and cultural contribution, as the essential anchor of presence, the umbilical cord that links those in the most trying of circumstances to their own lives:

This uniqueness and singleness which distinguishes each individual and gives a meaning to his existence has a bearing on creative work as much as it does on human love… A man who becomes conscious of the responsibility he bears toward a human being who affectionately waits for him, or to an unfinished work, will never be able to throw away his life. He knows the “why” for his existence, and will be able to bear almost any “how.”

Man’s Search for Meaning is a remarkable read, life-changing in the most earnest sense of the phrase. See more of it here, though no annotated excerpt could possibly do justice to the expansive richness of its entirety.