1532 Martin Luther's commentary on the Sermon on the Mount says of the golden rule: "With these words Jesus now concludes his teaching, as if he said: 'Would you like to know what I have preached, and what Moses and all the prophets teach you? Then I will tell you in a very few words.' There is surely no one who would like to be robbed. Why don't you then conclude that you shouldn't rob another? See, there is your heart that tells you truly how you would like to be treated, and your conscience that concludes that you should also do thus to others." (Raunio 2001 is a whole book on the golden rule in Lutherism.)

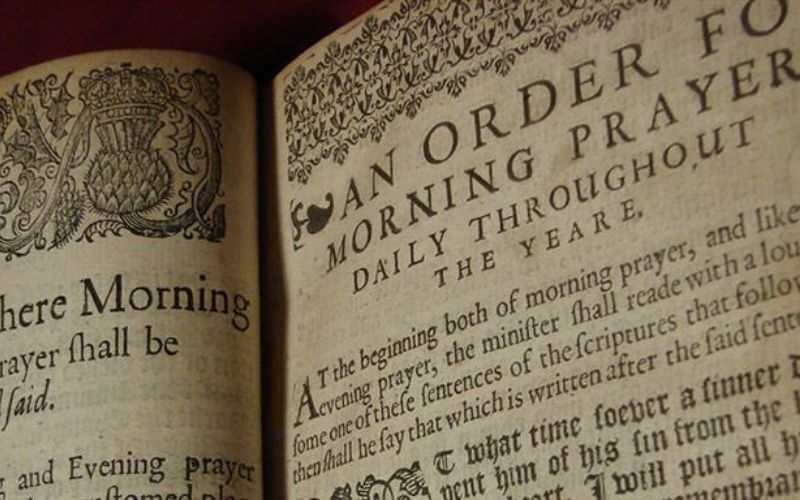

1553 The Anglican Book of Common Prayer's catechism says: "What is your duty towards your neighbor? Answer: My duty towards my neighbor is, to love him as myself. And to do to all men as I would they should do unto me."

1558 John Calvin's commentary on Matthew, Mark, and Luke says: "Where our own advantage is concerned, there is not one of us who cannot explain minutely and ingeniously what ought to be done. Christ therefore shows that every man may be a rule of acting properly and justly towards his neighbors, if he do to others what he requires to be done to him."

1568 Humfrey Baker uses the term "golden rule" of the mathematical rule of three: if a/b = c/x then x = (b × c)/a. At this time, "golden rule" isn't yet applied to "Do unto others" but rather is used for key principles of any field. Many British writers of this time speak of "Do unto others" but don't call it the "golden rule" (these writers include John Ponet in 1554, Giovanni Battista Gelli in 1558, William Painter in 1567, Laurence Vaux in 1568, John Calvin in 1574, Everard Digby in 1590, and Olivier de La Marcha in 1592).

1568 Laurence Vaux's Catechism says that the last seven commandments are summed up in "Do unto others, as we would be done to ourselves."

1599 Edward Topsell writes that "Do unto others" serves well instead of other things that have been called golden rules.

1604 Charles Gibbon is perhaps the first author to explicitly call "Do unto others" the golden rule. At least 10 additional British authors before 1650 use golden rule to refer to "Do unto others": William Perkins in 1606, Thomas Taylor in 1612 & 1631, Robert Sanderson in 1627, John Mayo in 1630, Thomas Nash in 1633, John Clark in 1634, Simeon Ashe in 1643, John Ball in 1644, John Vicars in 1646, and Richard Farrar in 1648.

1616 Richard Eburne's The Royal Law discusses the golden rule. Several other writers called the golden rule the royal law (after James 2:8), but this usage didn't catch on.

1644 Rembrandt's Good Samaritan drawing depicts a golden-rule example.

1651 Thomas Hobbes sees humans as naturally egoistic and amoral. Morality comes from a social contract that humans, to further their interests and prevent social chaos, agree to. The golden rule sums up morality: "When you doubt the rightness of your action toward another, suppose yourself in the other's place. Then, when your self-love that weighs down one side of the scale be taken to the other side, it will be easy to see which way the balance turns." (Leviathan, ch. 15)

1660 Robert Sharrock attacks Hobbes and raises golden-rule objections, including the criminal example. (De Officiis secundum Naturae Jus, ch. 2, §11)

1671 Benjamin Camfield publishes a golden-rule book (A Profitable Enquiry Into That Comprehensive Rule of Righteousness, Do As You Would Be Done By) and uses a same-situation clause (p. 61): "We must suppose other men in our condition, rank, and place, and ourselves in theirs." Later golden-rule books by Boraston, Goodman, and Clarke use similar clauses.

1672 Samuel Pufendorf's On the Law of Nature and Nations (bk. 2, 3:13) sees the golden rule as implanted into our reason by God, answers Sharrock's objections, defends the golden rule by the idea that we ought to hold everyone equal to ourselves, and gives golden-rule quotes from various sources (including Hobbes, Aristotle, Seneca, Confucius, and the Peruvian Manco Cápac).

1677 Baruch Spinoza's Ethics (pt. 4, prop. 37) states: "The good which a virtuous person aims at for himself he will also desire for the rest of mankind."

1684 George Boraston publishes a short golden-rule book: The Royal Law, or the Golden Rule of Justice and Charity. He says (p. 4): "Our own regular and well-governed desires, what we are willing that other men should do, or not do to us, are a sufficient direction and admonition, what we in the like cases, ought to do or not to do to them."

1688 John Goodman publishes a golden-rule book: The Golden Rule, Or The Royal Law of Equity Explained. He sees the golden rule as universal across the globe, deals with objections, and puts the golden rule in a Christian context. The golden rule requires "That I both do, or refrain from doing (respectively) toward him, all that which (turning the tables and then consulting my own heart and conscience) I should think that neighbor of mine bound to do, or to refrain from doing toward me in the like case."

1688 Four Pennsylvania Quakers sign the first public protest against slavery in the American colonies, basing this on the golden rule: "There is a saying, that we shall do unto others as we would have them do unto us - making no difference in generation, descent, or color. What in the world would be worse to do to us, than to have men steal us away and sell us for slaves to strange countries, separating us from our wives and children? This is not doing to others as we would be done by; therefore we are against this slave traffic."

1690 John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding contends that the human mind started as a blank slate and thus the golden rule can't be innate or self-evident (bk. 1, ch. 2, §4): "Should that most unshaken rule of morality, 'That one should do as he would be done unto,' be proposed to one who never heard of it, might he not without absurdity ask why? And then aren't we bound to give a reason? This plainly shows it not to be innate." (We can give a why for the golden rule - see my §§1.8 & 2.1d and ch. 12-13. But what is Locke's "No belief that can be questioned is innate or self-evident" premise based on? Is it innate or self-evident, or how is it proved?)