Schoolchildren in Armenia and Azerbaijan are too young to remember the Nagorny Karabakh conflict which created so much hostility between their countries. But their school textbooks feed them an unbalanced view of history that some experts believe will only harden attitudes for the future.

For decades, when both the republics were part of a single Soviet state, many Armenians lived in Azerbaijan – predominantly in Nagorny Karabakh – while large numbers of Azerbaijanis lived in Armenia.

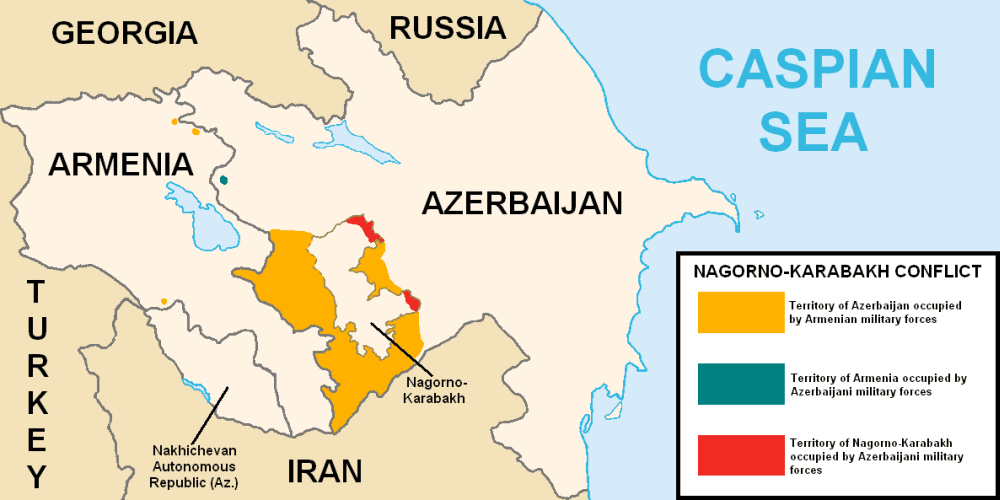

In the late 1980s, Armenians in Karabakh began campaigning for separation from Azerbaijan. Open warfare began in 1988 and only ended in 1994 with a ceasefire that left Armenians in control of Nagorny Karabakh and adjoining areas. No formal peace treaty was signed, and international attempts to resolve Karabakh’s status have so far failed.

By the end of the conflict, the ethnic Azeris of Karabakh and Armenia itself had become refugees in Azerbaijan, and the Armenians had fled in the other direction. So two populations that were once mixed became homogenous, each with a decreasing awareness of the other.

As the two nations developed separately over the past two decades, each established its own narrative of events not just around the Karabakh conflict but going back decades, even centuries. This is reflected in the very different content of school history books in Azerbaijan and Armenia, which colors the way children view both the other side and their own past.

Enemies and Heroes

Ashkhen, an Armenian in the 12th grade – the final year of school – says she has studied the causes of the Karabakh conflict and the way it unfolded, as well as the names of Armenian war heroes. She has concluded that peace with the Azerbaijanis will not come any time soon.

“They have to give up their claims to our lands,” she said. “Only when several generations have passed will it be possible for Azeris and Armenians to stop being enemies.”

Guljennet Huseynli, a 16-year-old Azeri schoolgirl in Baku, can list the sites of atrocities committed by Armenian forces in the conflict, although she is too young to remember it herself.

“How can we forget it? They killed our babies in Khojaly and Shusha,” she said, referring to events of the early 1990s. “My parents lost their friends and classmates in the war. They witnessed a huge influx of refugees to Baku. I’m learning about the bloody acts which the Armenians committed against my nation at school from teachers and textbooks.”

Khojaly is a case in point – an event in February 1992, during the Karabakh war, which is remembered in Azerbaijan as a massacre of hundreds of civilians fleeing the town – a tragedy of iconic importance. The Armenians’ memory is that it was one of the unfortunate incidents of war, with a lower bodycount than their opponents claim.

In their most recent attempt to forge an agreement, Armenian president Serzh Sargsyan met his Azerbaijani counterpart Ilham Aliyev in the Russian town of Sochi last month. One of the points they agreed on in a joint statement issued together with Russian president Dmitry Medvedev was that intellectuals needed to start engaging in dialogue in an attempt to bridge the gap between their two countries.

Many young Armenians, however, say they want nothing to do with their contemporaries in Azerbaijan.

Anna, 21, has plenty of internet contacts in various countries, but avoids interacting with Azeris.

“You can’t talk to them without a conflict arising. We start arguing about history, blame each other for things, attempt to convince each other, but we always end up with the same opinions that we started out with,” she said. “An Azeri schoolboy once wrote to me and started accusing me of various things, denying the existence of a genocide [against Armenians in Turkey in 1915-16], and calling Armenians ‘occupiers’. I was naïve enough to say that he had studied poorly at school, and suggested he read what it says in the textbook.”

The boy replied by quoting chunks of Azeri school books that supported his argument, such as one passage from a year-ten history text describing Armenians as “our eternal enemies” and detailing their offences in the early 1900s.

Tofig Veliyev, head of the Slavic history department at Baku State University, is the author of this textbook, and insists he had to use negative language in order to tell the truth.

“Those phrases give an accurate picture of the Armenians,” Veliyev said. “I would be falsifying history unless I described them like that.”

Similar language is found in the year 11 history book, which covers the Karabakh war period, and describes the Armenian forces as “fascists” who perpetrated various crimes.

Hasan Naghizade, a year 11 student in Baku, said it was right for history to be presented in this way.

“The author is Azerbaijani. Of course he’s going to incite animosity. That’s the way it should be,” he said. “They definitely don’t want to prepare us for peace. We don’t need peace. The Armenians have committed a lot of bloody acts against us. Peace would be disrespectful to those who died in the war.”

Azerbaijan’s education ministry approved the current set of history books in 2000. Faig Shahbazli, head of the ministry’s publications department, says the books were commissioned from historians and then checked for content.

One stipulation was that the texts should not contain discriminatory language. “Textbooks should promote democracy and tolerance, not hatred,” Shahbazli said.

But he added that words like “terrorist”, “bandit”, “fascist” and “enemy” did not breach that principle.

“Those words reflect facts. They do not provoke intolerance of Armenians. They don’t suggest the Armenian nation committed crimes; they merely indicate the nationality of those who did,” he said, adding that children were capable of distinguishing between individual wrongdoing and a nation as a whole.

Armenian’s education ministry conducts competitions for new textbooks every four to five years, with historians and publishers entering joint bids to be approved by ministry experts.

In Armenia, adolescents learn about the “War of Liberation” for Karabakh – which they call Artsakh – in year nine. The conflict is framed within the context of a long history from ancient Armenian statehood through to the “perestroika” period of the late 1980s, when nationalist aspirations began being voiced by various Soviet groups.

“The spread of liberation movements in the Soviet Union was a direct result of the politics of perestroika,” the book says. “The Artsakh Armenians were the first to rise up in defence of their national dignity. They would not accept that their historical lands had been forcibly united with Azerbaijan.”

This textbook is careful to avoid criticism of the Azeri nation as a whole, reserving it for the government in Baku.

Some say the book lays out the facts too drily, and would like to see it strike a more patriotic tone.

“There’s no national spirit in this material,” complained Anahit, 19. “Student should feel a sense of national pride in the valorous compatriots and in this magnificent victory won by the Armenians. This is lost in a dry recounting of events,” she said.

Mikael Zolyan, a political analyst in Yerevan, has studied textbooks from all three countries in the South Caucasus, including Georgia.

He said Armenian books were phrased relatively neutrally, and lacked the emotional language found elsewhere, he said. But they were still far from ideal as they presented history from an entirely Armenian perspective.

“You can’t expect anything else from history textbooks, but it would be right to present the other side’s point of view, even if it’s mistaken,” he said.

Arif Yunusov, an Azeri historian who has written on the Karabakh war, appealed to the authors of all textbooks to refrain from inflammatory language and to try about their influence on the younger generation.

Bellicose rhetoric makes a resumption of conflict more likely, he said.

“It is racism to portray Armenians the way they do in the [Azerbaijani] textbooks,” he said. “Those kids will grow up with hatred, not tolerance. How are we going to achieve peace then?

Old Grievances, Modern Narratives

It is not just recent history that leaves Armenians and Azerbaijanis with entrenched opposing views.

Another major difference concerns the mass killings of Armenians in Ottoman Turkey during the First World War.

Schoolchildren study these events in year eight, and read accounts of the Ottoman authorities driving Armenians into the desert and killing 1.5 million of them in a deliberate act of genocide.

Ruben Sahakyan, the historian who wrote the section on the killings, said he tried to avoid provoking emotional reactions.

“You must present only the facts, so that children can analyse them for themselves,” he said. “If you introduce emotional factors, you lose objectivity.”

Sahakyan argued that the Azerbaijanis were perpetuating historical myths created in Soviet times, whereas Armenian academics had spent the early years after independence in 1991 attempting to correct the record.

“We are writing real history, without exaggerations,” he said.

Turkey denies genocide and disputes the number of dead, and its stance is shared by its close ally Azerbaijan.

Veliyev, for example, said the reason Azeri children did not learn about the Armenian genocide is because it did not take place.

“It never happened. Why should we teach our children an invented history?” he asked.

Another set of historical issues about which Azerbaijani and Armenian teachers offer differing accounts is the period following the Russian Revolution and attempts to create nation-states in the South Caucasus.

In outlining the events of 1918, when Armenians and Azerbaijani forces battled for control of Baku, textbooks from Yerevan confine themselves to describing the short-lived independent Armenian state that was later subsumed within the Soviet Union. Azerbaijanis, meanwhile, read accounts of massacres committed by Armenians in Baku.

Baku school pupil Guljennet links the Karabakh war to 1918, suggesting a pattern of events that means Azerbaijanis must always be on their guard.

“Armenians killed Azerbaijanis at the beginning of the [20th] century. We forgot it and became friends. And what happened? They killed us again. Is there any guarantee they won’t do it in future?” she said.

Sahakyan dismissed such accounts as inventions.

“The Azerbaijanis have set themselves the task of making Baku an Azeri city, so in order to explain why Armenians were numerically superior there, they have invented mass killings that did not actually happen,” he said.

Armenian Academy of Sciences member Vladimir Barkhudaryan led the group of writers who produced the first post-independence history book, and continues to edit textbooks today. He argues that the reason why Armenian textbooks pay little attention to certain events is that they are not judged important.

“Insignificant events such as those that took place in Khojaly and in Baku in 1918 cannot be included. Schools have a clear timetable for the number of lessons into which the study of history has to fit. If you include this small changes in the book, it would be a huge tome,” he said.

Calls for All-Embracing, Rigorous History

In Azerbaijan, historian Yunusov said the selective approaches taken to events in Baku in 1918 illustrated the problem of drawing up a commonly-accepted narrative of the past. He said Azerbaijani historians talked only about March 1918, when many Azeris died, while their Armenian counterparts focused on September the same year when the Turkish army entered Baku and killed many Armenians.

He said this was wrong, and recommended instead that each side include the grievances of the other when compiling historical textbooks.

“Both sides use history as a political game. Armenian and Azerbaijani historians each claim to represent the public interest. But the historian should not be a provocateur; he should not represent the public interest. He should just present the historical facts,” Yunusov said.

In Armenia, Hrant Melik-Shahnazaryan, an analyst with the Mitq think tank, was similarly despairing of the spectacle of historians engaged in mutual recriminations.

“The [textbook] material must not agitate to create a victim mentality, but instead point to the mistakes that were made and the methods for avoiding them in future,” he said.

Melik-Shahnazaryan called for more intellectual rigor and analysis in historical accounts.

“You end up with a load of facts that you can’t connect together,” he said.

Richard Giragosian, director of the Regional Studies Centre in Yerevan, agreed that the general intellectual standard of Armenian school books could be better.

“Even the more recently produced textbooks have generally not been up to the minimum professional standard,” he said. “That’s particularly true of history books, which despite the higher expectations placed on them with the end of Soviet state control and ideology, tend to deliver only a meager and random selection of historical topics,” he said.

Haykuhi Barseghyan is a reporter for the Armenian weekly Ankakh and its website www.ankakh.com. Shahla Sultanova is a freelance journalist in Azerbaijan.

Arshlie Gorky

The great art of our people lies hidden in ruins and amid the daily life of remote villages. Our great art has been created by an innocent people who were never accustomed and never had through the sad ages any opportunity to tell the world about their achievements. We are a race of artists. And art is far superior to war because art creates while war destroys. Art preserves beauty while war produces only ugliness and unhappiness. Someday the world will become better acquainted with the art of Armenia.

~Arshile Gorky

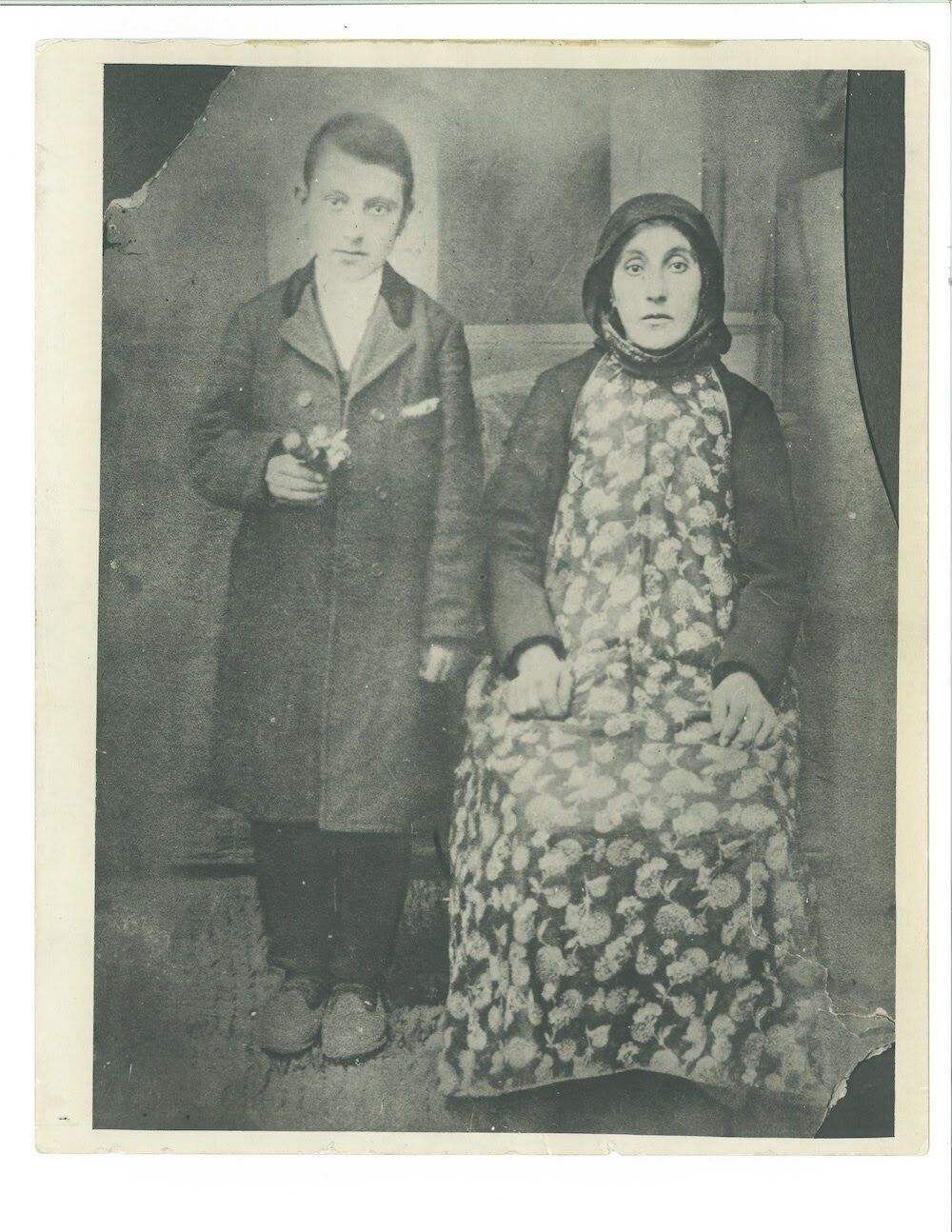

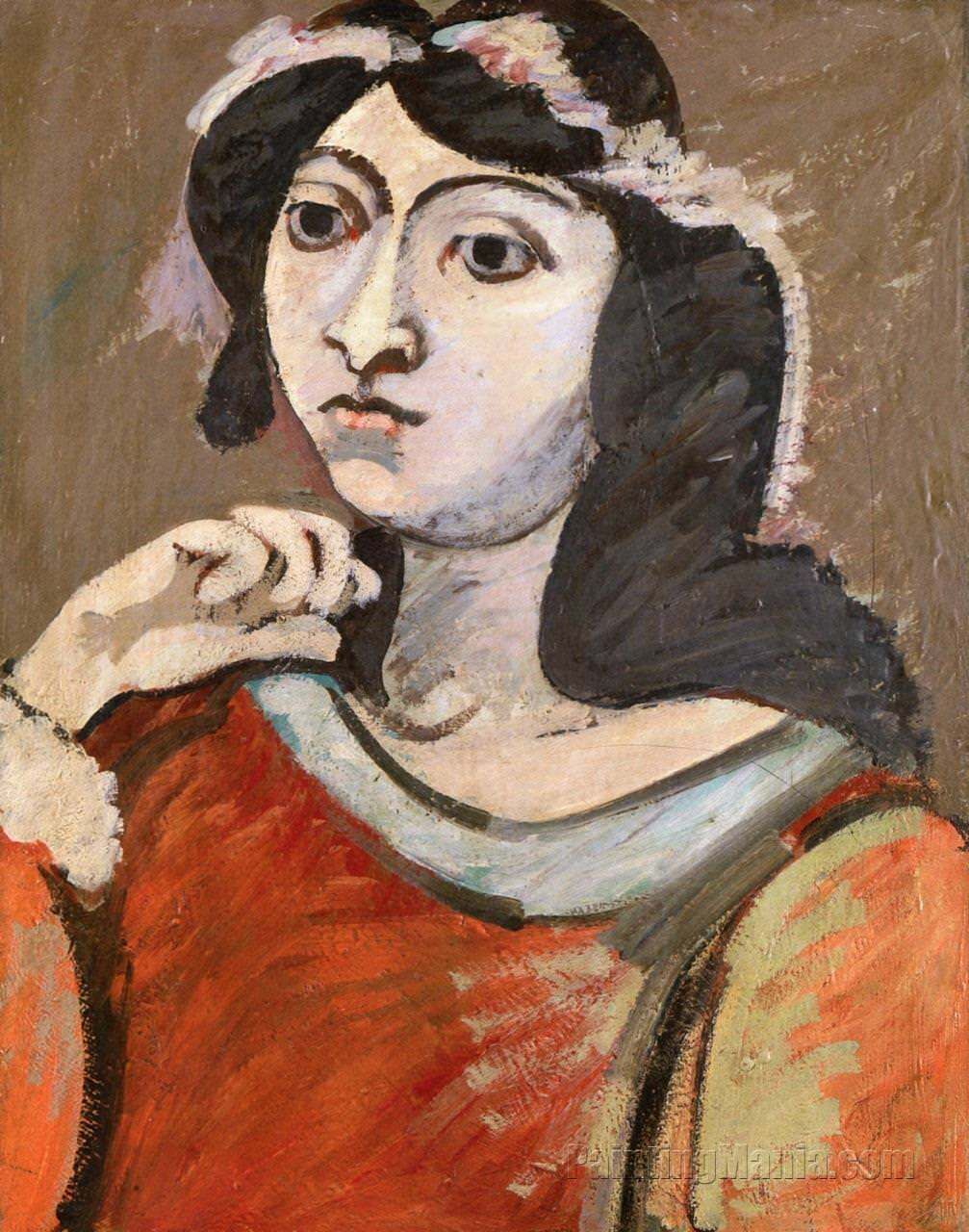

Gorky was born in Khorkom, Lake Van in 1904. As he was entering high school the Turks began the 1914 siege of Lake Van. Killed were both sets of his grandparents, six uncles and three aunts. His mother died in his arms on the 150 mile death march. One of his most famous paintings is that of his mother, depicting her as she was in his memory.

Gorky arrived in America on March 1, 1920. His father had left for America in 1908 to avoid the Turkish draft which was systematically putting to death the Armenians under the cloak of war.

In 1925 Gorky set up a studio in New York where he began his portrait painting. He adopted the name Arshile (provincial form of the name Arshak) and Gorky (Russian for “bitter”).

For 20 years Ashile Gorky had a productive life as an artist painting murals, teaching art and exhibiting his work. His work reflected his love for his homeland and his family. It was in 1945 at an exhibit at the Julien Levy Gallery that he was hailed by a critic as having produced the most original art in U.S. history.

It was at this time that tragedy struck Gorky yet again. He was never financially solvent in spite of his success. Then a fire in his Connecticut studio destroyed many of his paintings. An unfortunate automobile accident left his neck broken and his arm paralyzed, leaving him unable to paint. His wife and two children left him. Sad and alone, Gorky committed suicide by hanging.

Source: Avakian, Arra S. Armenia: A Journey Through History (The Electric Press, 1998).

Photograph and Painting: Gorky and his Mother

Siamanto: Beloved Armenian Poet

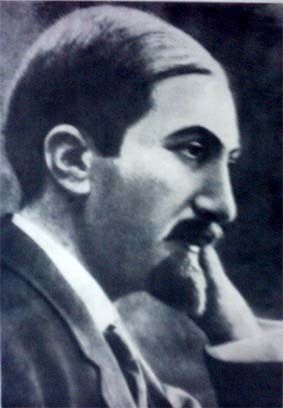

SIAMANTO (Atom Yarjanian) was born at Akn, Asia Minor, in 1878, of prosperous parents, who later moved to Constantinople. He was well educated.

During the years 1894-1896, the Sultan, Abdul Hamid waged massacres against the Armenians and Assyrians. It is estimated that as many as 300,000 people were executed. These events made a deep impression on Yarjanian. He sympathized with the revolutionary movement, and left Constantinople. Thrown upon his own resources by his father’s death, he led the life of a poor student in Paris, Vienna, Zurich and Lausanne. When the new constitution was proclaimed in Turkey, he returned to Constantinople, devoted himself to writing, and supported his younger brothers and sisters. A volume of poems published in 1902 under the pen name of Siamanto had made him famous, and other volumes followed. After the Adana massacres he came to America and spent a year in Boston, editing the Armenian paper Hairenik. He then returned to Constantinople, and he is believed to have been among the group of educated and influential Armenians of that city who were massacred in 1915, after barbarous tortures. Siamanto was a man of lovable character, and is considered one of the greatest Armenian poets.

Thirst

MY soul is listening to the death of the twilight. Kneeling on the far-away soil of suffering, my soul is drinking the wounds of twilight and of the ground; and within itself it feels the raining down of tears.

And all the stars of slaughtered lives, so like to eyes grown dim, in the pools of my heart this evening are dying of despair and of waiting.

And the ghosts of all the dead to-night will wait for the dawn with mine eyes and my soul. Perhaps, to satisfy their thirst for life, a drop of light will fall upon them from on high.

The Starving

O YE ancient and undisturbed Armenian plains of kind mornings,

And ye, golden fields, rich orchards, and pastures smiling with life,

Ye valleys covered with marble, flower-beds and kind and fruitful gardens—

Ye that create wine, which causes self-forgetfulness, and eternal, sacred daily bread!

Ye indescribable paradises of plants, birds, flowers and songs!

To-day, once more, at the lonely hour of my returning memory, of my sorrowful grief and delirium,

I call on your spirits, in bitterness live your life, and hopelessly weep for you!

Out of the blue, boundless space the fiery dawns open their lilies,

And lo! the proud cock makes his silvery voice resound.

The kotchnaks* click from village to village;

An harmonious flute joyously announces invitations;

And the herds scatter themselves over the hilltops,

With the dance of the industrious and busy bees.

And the peace sings. The flowers tremble. The buds seem to have the glances of saintly women.

The kotchnak is a small wooden board that is beaten with a stick to arouse the sleepers.

Source: Armenian House.Org: http://www.armenianhouse.org/blackwell/armenian-poems/siamanto.html

The Dance

In a field of cinders where Armenian life

was still dying,

a German woman, trying not to cry

told me the horror she witnessed:

"This thing I'm telling you about,

I saw with my own eyes,

Behind my window of hell

I clenched my teeth

and watched the town of Bardez turn

into a heap of ashes.

The corpses were piled high as trees,

and from the springs, from the streams and the road,

the blood was a stubborn murmur,

and still calls revenge in my ear.

Don't be afraid; I must tell you what I saw.

so people will understand

the crimes men do to men.

For two days, by the road to the graveyard …

Let the hearts of the world understand,

It was Sunday morning,

the first useless Sunday dawning on the corpses.

From dawn to dusk I had been in my room

with a stabbed woman —

my tears wetting her death —

when I heard from afar

a dark crowd standing in a vineyard

lashing twenty brides

and singing filthy songs.

Leaving the half-dead girl on the straw mattress,

I went to the balcony of my window

and the crowd seemed to thicken like a clump of trees

An animal of a man shouted, "You must dance,

dance when our drum beats."

With fury whips cracked

on the flesh of these women.

Hand in hand the brides began their circle dance.

Now, I envied my wounded neighbor

because with a calm snore she cursed

the universe and gave up her soul to the stars …

"Dance," they raved,

"

dance till you die, infidel beauties

With your flapping tits, dance!

Smile for us. You're abandoned now,

you're naked slaves,

so dance like a bunch of fuckin' sluts.

We're hot for your dead bodies.

Twenty graceful brides collapsed.

"Get up," the crowed screamed,

brandishing their swords.

Then someone brought a jug of kerosene.

Human justice, I spit in your face.

The brides were anointed.

"Dance," they thundered —

"here's a fragrance you can't get in Arabia."

With a torch, they set

the naked brides on fire.

And the charred bodies rolled

and tumbled to their deaths …

I slammed my shutters,

sat down next to my dead girl

and asked: "How can I dig out my eyes?"

Translated by Peter Balakian and Nevart Yaghlian

Vahan Tekeyan: His Vision is Alive and Growing

By Edmond Y. Azadian

Sixty-five years have elapsed since his death and the recognition of his legacy is universally expanding and his vision is living. Indeed, poet Vahan Tekeyan passed away on April 4, 1945 in Cairo, Egypt. He closed his one and only eye to the world, his other eye having fallen victim to his political adversaries. He was an early casualty for the cause of freedom of speech as thugs beat him to near death in 1916 for an editorial he had written. But he survived with one eye blinded. Later on he composed one of the most disturbing and movingly tragic poems about his eye titled, “My Only One.” He was a taciturn and bitter man, ahead of his time, and not fully understood by his contemporaries. He was a virtual recluse in the crowds, on whom a leadership role was thrust.

He was a poor man in terms of materials, however, despite his role in the community, he had left a will behind asking to be buried quietly; no eulogies, no fanfare, no special honors. Perhaps, deep in his heart he was convinced that no one could grasp his soul, his being, his vision to encapsulate in a eulogy.

His coffin was lowered into his grave, one flower dropped on his heart and a handful of soil from Armenia, where he longed to live his last years and be buried in the land of his ancestors.

But history had glory in store for him. Tekeyan is better known and respected today than during his lifetime. “My soul grows today and multiplies like an army marching to the battlefield,” he wrote in one of his poems; his reputation similarly “grows and multiplies” today for the young generation and for posterity.

Many people, who are not very familiar with Armenian literature (and that is not uncommon in these days when our values disintegrate) wonder why so many schools, organizations and cultural centers are named Tekeyan. The answer is brief — because not only he was a poet of universal standing, but also his persona embodied the suffering, the vision and the essence of his people; he symbolized the past, the present and the future of Armenia and the Armenian people.

He was a well-rounded person; a poet par excellence, a teacher, community leader, political activist and an organizational man. He has six volumes of poetry to his credit, fiction, essays and political commentary—although several volumes of poetry appeared after his death, but they mostly did not meet his standards nor his approval. He was a thorough and demanding writer and poet; he demanded more from himself than from others, that is why his austerity did not make many friends for him. He wrote poetry agonizing over each line and rhyme.

During his lifetime, his published poetry volumes wereHoker (Anxieties, 1901), Hrashali Haroutioun (Glorious Resurrection, 1914), Guess Kisheren Minchev Arshaloys (From Midnight to Dawn, 1919), Ser (Love, 1933), Hayerkoutiun (Songs of Armenia and Armenians, 1943) and Dagharan (Song book, 1944).).

These books contain a universe of poetry, emanating and radiating from the concentric form of self, then developing into tragedies and triumphs of his people, to end in a philosophical inquiry about God and the universe.

What Tekeyan willed to his people — in addition to his poetry — was his vision for Armenia’s survival and the Armenian people’s continued existence around the world. Today, the most topical issues on the political forum is the rapprochement between Armenia and Turkey, a process full of hurdles and pitfalls. The poet, deeply rooted in Armenian history has addressed the issue way back in 1930s, grudgingly acknowledging the need to overcome trauma and victimhood, to think clearly about the Armenian people’s political future. Recently, some essays by Tekeyan surfaced in the Armenian media, where a cautious but solid assessment was being made about Armenian-Turkish relations and an objective vision was being projected. Tekeyan knew the Turks better than anyone else; he had also witnessed the atrocity perpetrated against his people and fully reflected those scenes in his poetry. In one of his poems he revolted against God writing: “To hell, send us to hell which you made us know so well, and save your paradise for the Turks.”

Yet despite his occasional outburst and poetic hyperbola, he was somber and calculating when it came to charting the political future of his people.

Source: http://www.mirrorspectator.com/2010/04/14/vahan-tekeyan-sixty-five-years-after-his-demise-his-vision-is-alive-and-growing/

Poem

Forgetting

Forgetting. Yes, I will forget it all.

One after the other. The roads I crossed.

The roads I did not. Everything that happened.

And everything that did not.

I am not going to transport anymore,

nor drag the silent past, or that "me"

who was more beautiful and bigger

that I could ever be.

I will shake off the weights

thickening my mind and sight,

and let my heart see the sun as it dies.

Let a new morning's light open my closed eyes.

Death, is that you here? Good Morning.

Or should I say Good Dark?

Translated by Diana Der Hovanessian and Marzbed Margossian

← Go back Next page →