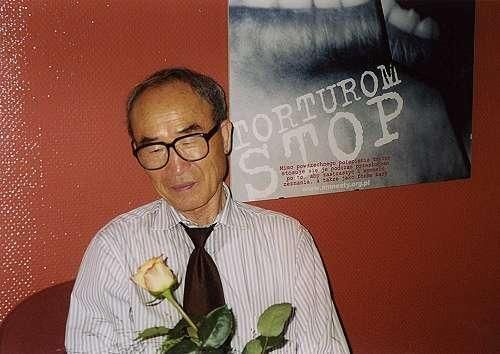

Ko Un 고 은 (Korean)

Ko Un was a witness to the devastation of the Korean War. He volunteered for the People's Army, but was rejected because he was underweight. He became a Zen Buddhist monk in the 1950s, and returned to secular life sometime in the 1960s.

Ko Un became an activist opposing the harsh and arbitrary rule of South Korea's president, President Park Chung-hee. His dissident activities led to several terms of imprisonment and torture. The democratization of South Korea in the late 1980s finally gave Ko Un the freedom to travel to other countries, including a visit to the United States and make a spiritual journey through India.

Selections from Ko Un's Ten Thousand Lives

T’ae-hyŏn: a Faithful Son

They were the most dreadfully poor family in our neighborhood

and, in addition to poor, short-handed too, for Chung-gil,

the fourth generation of only sons, had only one son.

For the fifth generation, his son T’ae-hyŏn was an only son too.

T’ae-hyŏn’s father kept coughing,

a hacking cough,

spitting up blood like a nightingale,

crawling out then crawling in and lying back down

with no money to pay for medicine.

At his wits’ end,

fourteen-year-old T’ae-hyŏn

went along to the dispensary outside the West Gate

and got a free prescription for his father.

Then he set out on a round of all the herbal druggists in Kunsan :

the druggist out in Shinp’ung-ri,

the druggist in Ŏ’ŭn-ri beyond Kaesa-ri,

the druggist in Sŏnjei-ri,

twenty druggists, more than twenty,

and by appealing to their sympathy obtained

one kind of tonic herb from each,

one kind of wild root from each,

one kind of everything.

Then he prepared the various medicines

in a pipkin propped on stones in place of a trivet.

After three years of sickness, color came back into his father’s face.

Thanks to his treatment the sound of coughing vanished,

banished from T’ae-hyŏn’s house,

the only son for the fifth generation,

even on chill spring nights while the apricots blossom.

Ha, the apricots are in bloom,

tomorrow morning they’ll be dazzling,

dazzling.

Old Jaedong’s Youngest Son

You wonder how on earth such a tiny thing can sing so well.

Even his father’s own version of Yukjabaegi

he sings more artfully than his father himself.

Soaring higher and higher, late summer dragon-flies swarm.

Note: Yukjabaegi is one of the fundamental Korean folksongs, improvised in a myriad of different ways depending on local or even family traditions.

Samdŏk’s Grandmother in Wŏndang-ri

If you pass behind the bier-shed, on past Wŏndang-ri village,

at the top of the young pine grove in Wŏndang-ri

stands Samdŏk’s family house.

With autumn work barely completed,

it’s the first to have a new thatch roof,

that yellow house, that shining house.

Samdŏk’s mother’s nickname is ‘Dusting.’

If her son’s father-in-law comes on a visit from his distant home,

as soon as he leaves she dusts the place where he sat

and dusts it again the next day,

muttering at the least excuse: ‘It’s dirty here, it’s dirty there.’

Everywhere is spotless – corners of rooms,

the yard outside – without exception anywhere.

No point in local spiders ever thinking

of spinning their webs in that house.

No point in local dust ever thinking

of settling carelessly in that house.

In that unluckily spotless house

the spirit of smallpox skillfully gained entry

and that was that!

Samdŏk’s mother lay lingering in her sickness,

confined for one month, two months, more.

Even while she was confined to her bed,

she kept a wet rag and dry duster near at hand

and after visits from the doctor

from outside the West Gate

she would wipe the spot where he’d been sitting.

Finally she gave up the ghost.

Her eldest son Sam-nyong drank his fill,

then when she was being laid out

he placed a few dusters in her coffin, blubbering:

‘Mother! Dust away up there to your heart’s content.’

Kim Sang-sŏn from Araettŭm

The two brothers Kim from Araettŭm, Sang-mun and Sang-sŏn,

were the pride of the neighborhood,

not only for stubbornness, but for miserliness into the bargain.

No one ever once went to their house

and succeeded in borrowing a rake.

No one was ever offered so much

as a steamed cabbage root to eat in that house.

When sweet potatoes were being steamed at Sang-mun’s,

all the doors were shut tight, the family ate alone.

Perhaps because the younger can never equal the elder,

Sang-sŏn, the younger, went one better

and on mornings after neighbors had celebrated offerings for the dead,

he could be found running here and there uninvited,

dropping in for a bite to eat,

and only leaving after getting a good meal,

to say nothing of three full cups of early-morning wine

to wash down the steamed fish.

When his kid wanted to eat taffy

and filched scrap iron,

old bits of plow,

or bits of hand-scales to exchange for taffy,

then got caught, and sworn at: ‘You thief!’

he would side with him and say,

‘The minute you eat taffy it turns into flesh and bones,

so come on, what’s the use of yelling at the rain?’

As for Sang-sŏn’s family affairs,

they never knew a lean year.

Things never went badly for that family

until the year after the start of the Pacific War

when Sang-sŏn’s wife was crossing an icy patch

with a water-crock on her head. She slipped,

she and the crock went crashing down,

and off she went to the world beyond.

Not one of the local lads offered to help carry the bier.

Bearers were hired at great expense of blood and tears

but then it was as if the banners and streamers were starched,

giving not so much as a flutter

as the bier moved off.

Note: When a villager died, usually all the neighbors would offer to help carry the coffin in the village bier as far as the burial place.

Elder Cho’s Wife

Cho Kil-yŏn from Saemal, over the fields from Kalmoe,

received a huge stretch of paddy and rich land at his marriage

but he squandered it all.

Now he earns his living farming someone else’s paddy,

or rather he entrusts it to his lazy wife and pretends to farm it.

Yet this Cho Kil-yŏn sings nothing but hymns.

Even in the privy, it’s hymns he hums

and Elder Cho’s wife is just the same.

For laziness, she’s first cousin to a maggot,

outdoing any outhouse-fed grub.

Even if cursed late-autumn rain comes pouring down

on the buckwheat on straw mats, the red beans on small mats,

she lies stretched out full length on the warmest part of the floor,

if anyone opens the door, she cries:

‘Aigu, what awful rain, what rain!

Well, cold rain makes a man, they say, and it makes grain tasty.’

Then she gently summons sleep again.

As if she were descended from some leisurely angler,

she gently summons sleep again.

Meanwhile Elder Cho’s daughter, Sun-bok,

works as hard as she can.

She comes flying across their rented field

like a butterfly,

like a bee on a radish flower,

scoops the grain out of the yard,

rolls up the sodden sacks, piles them in the store-room.

At which, good heavens!

faint late-autumn sunshine emerges,

banishing all thought of rain.

Beggars: Husband and Wife

When they have no food left

they go roaming around five villages :

Okjŏng-gol, Yongdun-ri, Chaetjŏngji,

Chigok-ri, and beyond Sŏmun ―

no, six, including Tanbuk-ri in Oksan County:

‘If you’ve any food, please, could you give us a spoonful?’

Their humility is so much humbler by far than

even the wife from Sŏnun-ri in Jungttŭm could manage.

The words ‘please, could you give’ are scarcely audible.

During the bleakest days of harsh spring famine,

when they cannot see so much as the shadow

of a pot of cold left-over barley-rice, they say:

‘Let’s go drink some water instead.’

Off they go to the well at Soijŏngji

to draw up a bucketful. Then those two beggars,

husband and wife, lovingly share a drink, and go home again

In the twilight thick flocks of jackdaws settle,

daylight fades into twilight,

as husband and wife pass over the hill at Okjŏng-gol.

In the twilight, smoke from a fire cooking supper

rises from only very few houses.

The Widows of Chaetjŏngji

If you ask for the widows’ house in Chaetjŏngji,

it’s well-known everywhere.

In that widows’ house

live a widow of eighty

and her elderly daughter-in-law of sixty-four.

Both buried their husbands early on,

then planted plantains and balsams along the fence

and lived peacefully together like elder and younger sister.

At last the mother-in-law, being old,

grew chronically ill.

Her daughter-in-law cleared away her excrement.

She had difficulty in even clearing her throat of catarrh

and what a stench of old piss on the reed mat!

The daughter-in-law seemed to grow older,

her back bent

but even on snowy days she went wandering over sunny slopes

grubbing up shepherd’s-purse roots,

always serving her mother-in-law.

When she boiled those roots in bean-paste soup,

the perfume spread throughout all the village.

Father’s Second Sister Ki-ch’ang

She got married.

Abandoned, she returned home.

She crushed balsam flowers to dye her nails.

She dyed all ten finger-nails,

saying nothing,

shunning even heaven far above.

Maternal Grandfather

Ch’oi Hong-kwan, our maternal grandfather,

was so tall his high hat would reach the eaves,

scraping the sparrows’ nests under the roof.

He was always laughing.

If our grandmother offered a beggar a bite to eat,

he was always the first to be glad.

If our grandmother ever spoke sharply to him,

he’d laugh, paying no attention to what she said.

Once, when I was small, he told me:

‘Look, if you sweep the yard well

the yard will laugh.

If the yard laughs,

the fence will laugh.

Even the morning-glories

blossoming on the fence will laugh.’

Su-dong and the Swallows

Su-dong’s family is only his parents.

When they’re out at work

and he is playing, alone,

looking after the house, he gets bored.

Home alone, his only sport is idly pulling weeds,

until every year in early spring the swallows arrive.

Filling up the empty house, the swallows become his family.

As droppings fall on Su-dong’s head,

the swallows fill up the empty house.

The brood hatches, then in the twinkling of an eye,

the chicks grow up

and go their separate ways,

at which he finds himself bored again.

The yard is suddenly that much bigger.

Late in autumn the swallows,

setting off to fly fast over hills and seas,

over seas and oceans,

the swallows leaving for lands beyond the river,

for distant south seas,

gather on the neighborhood’s empty washing lines

and sit in rows, preening their breasts with their beaks

before setting off.

Looking up at them all, Su-dong feels utterly lonely.

Feeling lonely

means growing up.

‘You’re leaving now, you’ll be back next year.

Good-bye for now.’

He gives each of the swallows a name:

Chick-sun,

Chick-ku,

Cheep-sun,

Cheep-bo.

Arrows

Body and soul, let's all go

Transformed into arrows!

Piercing the air

Body and soul, let's go

With no turning back

Transfixed

Rotten with the pain of striking home

Never to return.

One last breath! Now, let's leave the bowstrings,

Throwing away like rags

Everything we've had for decades

Everything we've enjoyed for decades

Everything we've piled up for decades

Happiness

All, the whole thing.

Body and soul, let's go

Transformed into arrows!

The air is shouting! Piercing the air

Body and soul, let's go!

In dark daylight, the target rushes towards us.

Finally, as the target topples in a shower of blood

Let's all, just once, as arrows

Bleed.

Never to return!

Never to return!

Hail, arrows, our nation's arrows!

Hail, our nation's warriors! Spirits!

Ko Un on Writing Poetry

If asked why I write poems, I still haven't found the answer. On the way, I have been an awkward farmer, a bird, and a shaman with tears. Meanwhile, words were my religion.

When poetry didn't come I dug into the earth. Some of the spirits of poetry that were buried in the earth entered, trembling, into my body. On windy days, as my down rose, I kicked off from the end of the bough. Up in the air several poems were floating. Passing them I by chance pecked at one or two and ate them.

Often I went mad.

I cry. Crying, or the murmur of brook or river, or the sound of waves striking a thousand-year-old cliff, are all part of the same family. In the dance of the white foam, a poem was present. I must broaden my world a bit. I will not be confined in this present world only.

Time with Dead Poets

We are in one region of the universe,

sometimes a merciless wilderness,

sometimes a womb.

Here each of us

is not just an individual living poet.

Here we living poets have been changed

into something else, an unfamiliar backcountry.

No sound passes beyond the boundaries of extinction.

Our bodies sometimes feel heavy,

sometimes lighter than our hearts.

The souls of dead poets

have entered each of our bodies,

folded their weary wings, made their abode. We grow heavy.

I am more than myself.

You are more than yourselves.

We sing in the universe's dialect,

in the new mother-tongue of dead poets.

We began alone

then we came together. Our burdens are light.

As waves in huge columns exploded aloft, swirling madly,

then, next morning, settled again,

as gulls emerged from hiding, terror ended,

no longer trembling,

went soaring aloft, drawing the most refined circles,

one died.

A poet, someone whispered.

At times, a day was as long as a slowly evolving intestine;

at times, a day was short like a newly-born baby gull's wings.

Because the dead poet's remaining lifetime had settled

at the heart of each of our lives born of the egg myth.

In the void above high plateaux at 5000 meters

a dry, gaunt Tibetan gull is flying.

A very, very long time ago,

a continent came rushing near, collided.

Then the area that had been once a sparkling sea

turned into the Himalayas.

The gulls lost their ocean.

They cried aloud.

These gulls must be second-generation, twelfth generation, if not 1302nd ...

A next time comes.

A next time comes.

Their cries finally became songs, became poems.

So each of us

is a living poet.

And not only individual living poets

but three poets, seven poets, eleven, in this world and the world after.

We are the very sensuality

of the time in which we come and go.

Now the memorials we make for other souls

are one with the memorial someone else will make for each of us.

Our meeting here

is bound to leave scenes of multiple separations and deaths

in many places, not only here.

Here it is!

in our backcountry there is a lake. Amazing.

On the water's surface, before and after we close our eyes,

a white water lily is floating.

Wretched is the poet who has never written an elegy.

We must sometimes shoulder that wretchedness

and write a new elegy.

That is another name for a love song. A flower.

Yes! we need sorrow.

The lake remembers its ancient sea.

← Go back Next page →