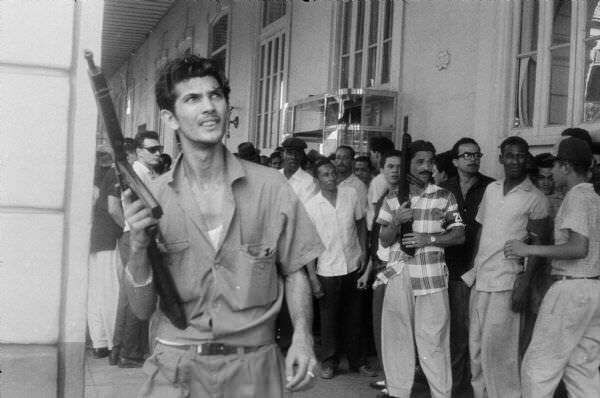

Soldiers in Crowd, Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

HOME TO ME is a small apartment in a row of old buildings that face across Manhattan's First Avenue in the direction of the East River. My view of the water, though, is blocked by Bellevue Hospital, a symbol which some people call depressing but which I find is a reminder of compassion and challenge, too.

After I came back from Lebanon and sat down in the green chair behind the broad wooden table that faces the noisy typewriter, I forgot for the first time in my life to ask if I was a reporter. I was too busy telling what I had to report.

Not till thousands of words had ground through the typewriter did I begin to understand the pattern of the history I'd been covering, though. I wanted to go on thinking of the typed sheets of paper falling one after another out of the machine as just the output of a story teller, simply the product by which I made my living.

They were stories, yes. Telling them fed me, yes. But their substance was not innocent.

I had become an interpreter of violence. I'd covered three revolutions in three years-Hungary, Algeria, Lebanon. One editor summed it up far too neatly when he remarked, "You don't mind, do you, if we call you our special correspondent to the bayonet borders of the world?"

I did, but not half so much as I minded the larger truths that the revolutions had failed. Hungary had fallen to the tanks. Brother still fought brother in Algeria. Rioting continued in Lebanon. But men continued to hope and fight for a better world.

Three weeks later, I was sitting in a Miami hotel room staring at a telephone. As soon as it rang, I would be on my way to cover my final revolution (to date, that is)-probably the most significant revolution of them all.

The people of Cuba had started to hope, too, and I'd been sent by THE READER'S DIGEST to find out what was happening to them.

The phone did ring, finally. I heard a man's deep voice saying "Cohen here," the code which the Cuban exiles hack in New York had told me would identify the leaders of the anti-Batista movement in Miami.

Cuban Rebel Shooting at an Airplane, 1958, Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

I expected to be flown at once to Havana but instead I spent five days in a near-bare, cheerless tile-floored office in the Congress Building, only a few rooms away from the one where a long time ago I'd earned fifteen dollars a week as an air show city editor. The office was the clandestine headquarters of the Cuban underground in Miami supporting Fidel Castro. Hour after hour I interviewed Cubans fleeing from Batista. From their words and voices, many still shrill with fear, I tried to piece together a picture of the reign of terror.

The looting of Cuba on a lavish scale could not be hidden, and Batista first tried to anchor his critics to his cause as he had anchored the army-with a chain of gold. But not all the critics were corruptible. And stolen pesos could not dry up the rising hatred felt toward him by the people he was robbing. There simply were too many of them. So at last he decided to try to silence them by the tried-and-true method of fear.

Around his empire of corruption, Batista built a secret. police organization. The letters SIM and the sleek olive. drab radio cars with submachine gun barrels poking through their windows appeared in the streets. Every police station in the large cities was said to have its own torture chamber. A fifty-year-old woman schoolteacher who during an interrogation had been violated with a soldering iron in Havana's XII district, February 24, 1958, described the building. She said the chief's office had walls of tile and drains in the floor so it could be cleaned with a hose each day.

Another told me lie knew of a community destroyed by the Cuban Air Force with air-dropped flaming gasoline. He asked me almost diffidently if there was any other country that could have supplied the Bastistiano planes with the napalm-the gasoline jelly bombs-but the United States. I said I did not know, but I did not add that the answer probably was no. (Later I was to see the wreckage of the burned-out town of Mayeri in Oriente, and to photograph pieces of the distinctive silvery metal casings developed by U.S. forces during World War II for air-dropping napalm.)

In Miami, I reminded my Cuban friends that the United States had embargoed all arm shipments to Batista, including those for hemisphere defense, in March of 1958 (it was now mid-November of the same year). They derided the effect of the embargo, saying that Batista's forces had been fully equipped long before with the very weapons now being turned on Cuban civilians.

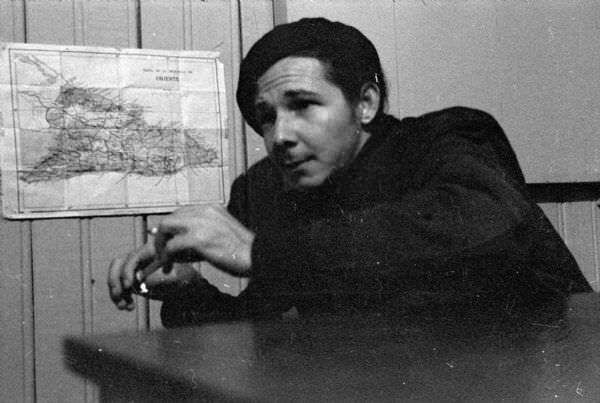

Fidel Castro, 1958, Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

For two years Fidel Castro had been a magnet for venturesome American newsmen, an off-beat folk hero in the tales of foreign correspondents. First Herbert Matthews of The New York Times and then Andrew St. George, later of Life, had trekked deep into the Sierra Maestre mountains of Oriente Province to bring back reports that Castro's forces were taking on planes and armored cars with hunting rifles and shotguns-and winning. In the end, some twenty reporters had been assigned to go through Batista's lines to Castro. Exactly half of them made it; the rest, identified enroute by Batista's secret police, had been loaded at gunpoint onto the first Miami-bound airplane.

Dr. Carlos Busch, who headed Castro's underground in Miami, told me bluntly that I'd get through-if I let him ship my cameras and field gear into the Sierra Maestre area clandestinely. He said I was to travel as a tourist and that to carry the leather camera case containing my Leicas, boots and Kabar would expose the courier who must accompany me to arrest and torture.

I demurred, saying I must go with my cameras and offered to be moved blindfolded, as I'd been in Algeria, over the secret route to Castro. He replied that I'd thereby defer delivery to the Cuban revolution of ammunition weighing whatever I did. The most important rule for negotiating with a jittery underground movement is don't argue, so I shortly left my gear in the custody of Castro's representative in Miami. As readers more astute than the writer will have guessed, I never saw it again. Eventually my fury over the loss of my cameras simmered down (other reporters too were victimized by this kind of Castro trick, one of them losing a motion-picture sound camera into which he had just sunk his life savings), but to have let the trench knife given me on Iwo Jima pass into somebody else's hands-for this I can't forgive myself.

However, one twist to my last interview with Dr. Busch turned out to be pure comedy. His words of parting were, "We'll get you through so long as you have made absolutely certain no one knows that you are in Miami now. Batista's spies are everywhere. A phone call to one of them and the SIM will be waiting for you at the airport in Havana."

I assured him solemnly that no acquaintance of mine but my editor knew where I was, stepped out onto the sidewalk before the Congress Building and almost ran into the Marine colonel who had helped train me in California a few years before.

"Dickey Chapelle!" he shouted. "Whatever are you doing down here? Don't tell me; let me guess-of course you're on your way to Castro!"

The colonel had a colonel's voice and I was sure it hadn't stopped echoing this side of the Cuban coast. My loyalty to the Marine Corps underwent a quick heavy strain. The officer read correctly the dismay on my face, quickly shook hands and we parted.

I was shortly in the air on a commercial plane to Havana in the company of a courier from Dr. Busch's office, a plump dark girl about twenty-five with tremendous heavy-lashed eyes. I admired her composure on the trip, for the risks she was taking were real ones. As the plane banked to land in Havana, she crossed herself and her lips moved. I discovered I was praying right along with her.

The inspection by the police at the airport was cursory for both of us. I said I was an employee of a New York firm of portrait photographers on a two-week vacation and nobody challenged it. I'd just had my scarred passport replaced by one innocent of stamps, not for this trip but because the old one had no blank pages. And a fresh passport was typical of a casual vacationer.

None of these good omens, though, were going to be too helpful on the next lap of the trip. The Batistiano lines around the airport in the capital city of Oriente, Santiago de Cuba, at the other end of the island, had been tight for a year. Now word came that the city was virtually besieged by Castro's forces. I would need a really good story to tell before I'd be passed through the city proper and out into the province.

The story on which I stumbled came straight from the Marine colonel's unwelcome shout. He'd thereby reminded me that there were Marines on duty at the U.S. naval base near Guantanamo City, only forty miles from Santiago.

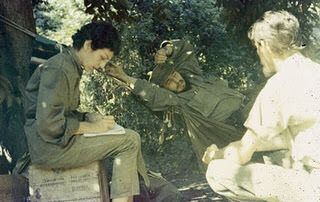

Raul Castro, Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

So before I took off from Havana by Cubana Airlines with my girl courier, I dressed in spike heels, dangle-earrings and a pale blue fluffy shirtwaist. I tucked into a sequin-trimmed wallet a picture I'd made of a baby-faced Marine with a scarred chin whose name unfortunately I could not remember.

The moment came when none of these preparations seemed overdone. My courier was being passed without drama by a brisk Cuban police officer at the Santiago airport barrier. I had drawn a large razor-eyed officer, and my luggage still lay unpacked. Although he'd made sure there was not a single item in my suitcase that any American tourist would not ordinarily carry, he clearly was not satisfied. In English he snapped at me, "You say you are a tourist?"

I nodded dumbly.

"How can you be?" he began with an air almost of sweet reason. "If you want to tour, you must get back on the airplane for Havana. There is nothing for visitors here, nothing. The city is encircled by the bandits. We do not even have enough to eat. No, you cannot be a tourist here."

I said defiantly, "Well, I am." And then I decided to capitalize on my nervousness right away. I looked around as if to be sure nobody else would hear me, and dropped my trembling voice an octave. "You see-you see, Officer, I'm trying to evade the authorities."

I had succeeded only in puzzling him a little. "Evade the authorities?" he repeated.

I said, rushing my words, "American authorities don't want Marine-uh-Marine wives in the vicinity of the Guantanamo naval base." And as if revealing a treasure, I picked my glittering wallet out of the shambles the officer had made of my purse and opened it to the picture of the Marine. "Isn't he handsome ..." I sighed. He was, too.

But I was worried; I'd thrown my Sunday punch. One more question of fact and I was done. I didn't know the name of a single Marine on duty at Guantanamo.

The police inspector said doubtfully, "You're married? Why don't you wear a wedding ring?"

Score the round for him. I was playing the Mata Hari game just about as badly as I had done the last time. I hadn't thought of a wedding ring. I blushed at my defeat. And then realized a blush could mean something else.

"Well, we're going to be married . . ." I said.

The officer's secret police mentality slid into gear at once. Incredibly, he was smiling. Obviously he had doubts about the position of marital bliss over international complication.

But stolen romance outranked it every time.

"Okay, go ahead," he said, blessing me with a fourteen karat leer.

Once among the winding sidestreets of the city proper, my courier delivered me to the quarters I was to occupy till I could be led to Castro: a deluxe tourist court on the outer edge of Santiago where the life of high adventure included a fine restaurant, electric light, hot and cold running water and a marathon gin rummy game in English. Other players included an oil expert on his way back home to Texas, a shellfish specimen collector from the University of Michigan and my colleague, Andrew St. George.

Andrew at once told me to beg, borrow, steal-or even buy -new cameras at once since my own certainly never would be given back to me. Although I was outraged, his advice made sense. I insisted my girl courier take the risk of driving me around the city while I, with the worst possible grace, assembled a new picture-taking outfit. I found a Japanese :.5 mm. camera in a photo store, picked up half a dozen rolls of dusty film from every drugstore we passed and finally located a Leica I could borrow from one wealthy Castro sympathizer and a lens from another. The only good thing I could tell Andrew that evening over our card game about my mismatched photo gear was that it was better than being empty-handed.

Andrew was sage again. He told me I'd probably be the only correspondent with Castro during the month; he himself was on his way to New York and other reporters had left earlier; the bearded revolutionary's campaign seemed to be stalled at the gates of Santiago. Glumly I agreed I probably was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

No doubt such mutual misjudgments are the only certainties of journalism. As matters worked out, before I left Cuba nine weeks later, I was to see a whole sequence of infantry actions, the end of the fighting and the installation of Castro in the Presidential Palace in Havana-the biggest news stories out of Cuba in many years.

Celia Sanchez taking notes from Fidel Castro, Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

My actual crossing from the city's edge into the countryside where Castro's forces already ruled was an anticlimax, an uneventful walk with another girl courier across a golf course. The jeep that met us on the far side was driven by a bearded rifleman who wore an arm patch reading 26 JULIO (the 26th of July movement commanded by Fidel Castro). After a few hours of grinding across cane fields and fording streams, I was deep into Oriente Province at the farmhouse headquarters of the forces under the orders of Fidel Castro's younger brother, Raul.

On my way to interview Fidel Castro, I covered four actions along the Central Highway in Oriente Province during the next week-the cuartel surrender at Alto Songo, the burning of the fortress near the hamlet of San Luis, an assault at the town of Jiguani and the last mortar barrage by the Batistiano in the village of Maffo. I didn't see the barrage, but I was a backhanded casualty because of it.

A few minutes before midnight on December 15, the main square of Maffo was a No Man's Land. No shell or bullet raked the buildings around it, though. The army garrison behind the fortress walls on the north side of the square and the rebels' thin line tip the main street had agreed to an hour's cease-fire from eleven o'clock to twelve.

The Batistiano stronghold looked utterly dark and still as if it had just sucked in its breath. Nothing moved among the houses of the village because most of the families had left to take shelter in the nearby cane fields.

But the rebels affronted the tension with both light and noise. At their command post in the drugstore, the shutters had been flung up. On the glass counter behind the door stood a flaring gasoline pressure lantern, the only light in Maffo. Beside it was a portable phonograph, turntable rotating busily. The speaker blared the militant hymn of the rebels, filling the night with brass notes and bass beat.

When the song was done, a rebel officer stepped from the shadows and picked up a bulbous silver microphone. He was stocky, and the harsh light from the hissing lantern gleamed from the triple-V of a captain's insignia on his shoulders and from the heavy sweat on his face. Deliberately placing himself to be an easy target if the garrison broke the cease-fire, he began a hoarse harangue. He was pleading with the soldiers to surrender at midnight instead of resuming firing. He called them friends and brothers.

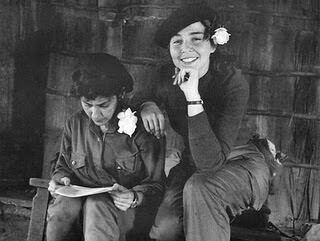

Celia Sanchez and Vilma Espin, Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

As he talked, it came to me who he was-Luis Orlando Rodriguez, the Havana publisher whose newspaper La Calle lead been repressed repeatedly by Batista. Here, six hundred miles from his confiscated presses, he was known as Capitano Orlando, one of the ranking intellectuals of Cuba in uniform.

He set the microphone down on the glass counter with a jarring noise, and a rebelde switched on the turntable again. The hymn crashed out into the darkness and the captain stepped over beside me at the building wall. He pointed to my raised Leica. "You must have thought they were going to shoot me," he shouted over the music.

I said nothing. He looked down at the face of his gold wrist watch. "Not now, they won't shoot. But the cease-fire will end soon now. Then I think they will fight very hard. It is-it is-" He was speaking English and he groped for the right word. "It is tragic. I will try to talk with them again, but-" He passed his hands over his face, smoothing for an instant the deeply carved lines of weariness.

He went on, "You, Americana, get in the jeep now and get out of the light. My mortar crew has no ammunition; there is no need for them to stay here either. They will go away in the jeep too." Out of the shadows in the back of the store four young rebelde moved uneasily, their eyes fixed on the captain's face. The nearest was immensely tall, brownskinned, very thin.

The captain said, "This man's name is Luis like my own. He will show you the way. Now go."

Stepping quickly through the buildings and running bentover across a cavernous side street, Luis led the four of us to a jeep. I had come up to the front in it earlier, and I knew its tense and tiny driver, Georgi, as the best jeep mechanic in the battalion.

Georgi did not need to be urged to move out. Deftly he started the motor without gunning it so the brassy music covered its noise. In low gear, lie sidled along a curving lane till we were behind a ground rise covered by bushy trees. Then he parked and Luis led us toward a deep ditch. "If we lie flat here we are safe from anything but mortars." He threw himself beneath the ditch lip.

I did as he had done. He went on with a breathy chuckle, "I never thought to see an American in the mud like a pig, as we lie now."

I didn't reply since I was under his orders. But I felt a flicker of indignation. Taking cover when you had somehow been reduced to the role of an ineffective struck me as no indignity at all. Yet in Luis' eyes I knew I had compromised my country's face. I pondered what else I-

A mortar shell crumped down, inexplicably far to our left. The lantern glimmer we had seen from the drugstore went dark and the phonograph choked off in mid-bar.

Revolutionary Infirmary, Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

". .. not good here . . ." I heard Luis gasp as we ran for the jeep. As we three climbed in the front, I sensed half a dozen others piling into the back.

Georgi's foot was heavy on the gas pedal. The rutted lane jolting under us became the smoother asphalt of the main road out of Maffo. There was a crackle of rifles behind us, many talking at once. Luis was shouting at Georgi-something about the one sure mortar target in the whole village being where we were. It made sense that the mortars from inside the cuartel would aim to cut off the main road.

Georgi acknowledged this likelihood with a grunt. The jeep suddenly was speeding faster than I had ever ridden in a jeep before. We crested a hill and started down, going faster and faster-too fast to control and still accelerating .. .

I was sitting in front between Georgi and Luis. The jeep had never had any brakes in the time I knew it. Now the clutch had gone out. There was no way to stop it. And we were going downhill.

The men were jumping from the back seat. Suddenly Georgi was not with us any more; the driver's seat to my left was empty. I knew it was too late for me to jump. Luis had not gone either and as I curled around my own knees with my shoulder blocked into the dashboard, I could sense him moving over me like a shield.

The jeep at its highest speed now brushed against an earth bank on the left of the road. It rocketed into the air. It flipped upside down. Luis and I were dropped free.

I did not hear the jeep's final head-on crash into the other bank. In total darkness on warm asphalt my breath came hack to me; I was lying on my stomach with my arms under me as if they had helped to break my fall. The first sound in my ears was a man's scream. It came again. Then it was throttled. I tried to move toward the sound and suddenly knew my numb right leg would not carry me.

The thudding mortar fire and the stuttering rifles seemed very far away. I had a quick mental picture of the dark downhill road, strewn with hurt and gasping bundles that had been people.

The first bundle to which I crawled was Luis, still shuddering in his struggle hack to consciousness. I could not tell if he was hurt. Then Georgi stood in front of us, a silhouette with bowed shoulders.

"Horses . . ." he was saying. "I go for horses from the finca ..."

Luis pushed himself almost to his knees. Then he fell back, still not able to speak.

Georgi went on, "-but you'll have to wait-to go to the hospital. The one villager-he who screamed-is dying. I think. Gasoline drum fell on him. Cut him apart." Georgi tried to take a deep breath and his voice cracked as the last words spilled out. "Luis, I know I should not have jumped . . ."

Then he was gone in the darkness. I was not sure Luis had even heard him. After a time, Luis sat up. He gritted his teeth, very white in the black around us. "He knows. He knows it shames us, what he did. It was his duty-to stay with the jeep."

Through the two-hour trek on plodding farm horses by which we reached the place Georgi had called "the hospital," Luis and he, pacing on either side of me, said no word to each other.

The place for the wounded was a long crooked shed used in peacetime for drying fresh-picked coffee. It was staffed by two doctors, a bearded older man and a sturdy light-haired woman. They wore civilian clothing with 26 JULIO armbands.

Under the sheet-metal roof of the shed hung two flickering kerosene lanterns. Toward one end stood six shabby beds and a canvas cot. A rolled mattress disgorging its stuffing rested against one wooden wall. In the center of the space stood a dining room table. A white enamel basin and a canvas roll of surgical instruments gleamed on it.

At first there were three patients in the beds, two young rebels motionless under rumpled blankets, and one old man with graying stubble on his chin who tried to sit up under a torn sheet so he could see the knot of people shifting around the next bed. They were carrying an inert form in their arms-the man on whom the gasoline drum had fallen.

The woman doctor, a surgeon, had done for him, what she could but as she turned away I was not sure if she thought he would live or die. The woman was surprisingly young and inexpressibly weary. She was holding a morphine syrette in her hand, the kind American army medics carry on their belts. With a sad spare gesture she threw it into a cardboard carton of used bandages. "Final," site said to no one in particular. The last anesthetic.

Then the bearded doctor was telling Luis and me that we must crawl out of his way. My ankle was not broken, only sprained and swelling, and Luis, though holding his stomach in pain, didn't seem in shock any more. We had been sitting on the earth floor with our backs against the rolled mattress, now needed for another bed. Then all the casualties from the mortar barrage arrived at almost the same minute. Before the next hour passed, there were a dozen newly wounded in the hospital. Four bodies, candles burning at their feet, lay in a row at the dark end of the shed. The floor was wet with blood.

The last hurt man was the most memorable. His eyes flickered sometimes but he did not seem to be conscious. His midsection was swathed in rags. With one arm he clutched his bandages. The other hand seemed to have a life of its own, opening and closing in spasms.

Standing over him I saw the stocky figure of Capitano Orlando.

"Captain, are you wounded?" I asked, half crawling to his side. I did not think at first that he had heard me. Not taking his eyes from the hurt man's face, he answered, "I am all right. But he-he has a bad wound. Shrapnel. In the abdomen."

Then the captain seemed to see me. "This man was my very good friend for a long time. It is not right that he should be-like this. Not while I am-unhurt. You see, we tried so hard to keep them from shooting. Even after the cease-fire was over, we kept on talking to them. We put the loudspeaker on the truck and we drove into a field. We did not stop talking. Perhaps someone told them where we were -somehow they found out, and their mortar hit the truck. Over and over.

"Look, Americana," he went on, narrowing his eyes at me, "this man's story you must tell even if you do not tell other stories. For he is not even a Cuban, only one who hates tyranny. He is a Dominican. He fights with us against Batista now so we will fight with him against Trujillo later. If-if ever he is able to fight again."

I nodded. I knew why the editor-capitano felt this story was important. About one out of every ten rebel fighters I'd seen came from some other Latin American land; there were so many non-Cuban volunteers to Castro's forces-from Venezuela, Nicaragua, Argentina, Guatemala, Ecuador and Panama-that the rebel leader had eliminated an oath of loyalty to him lest they jeopardize their chances to go back home later.

The woman surgeon stood on the other side of the hurt Dominican. "I know he is your friend, Capitano Orlando," she said. "But I cannot operate now. I have no light, no anesthetic. And it will be a long operation. We will try to keep him alive until tomorrow. Then I will tell you if I can save him."

The captain had been gazing at his friend. He turned and gestured to me. "I have a truck outside and I am going to Dr. Fidel now. If you can climb aboard, come with me and you shall see him." And he handed me his carbine to use for a crutch.

Through a pelting tropical downpour at dawn the next day, I was led a mile on foot, limp and all, out to a cave on a hillside, the command post for the 26th of July forces. For the next six days, I shuttled from this cave to a second one to a farmhouse which served successively as Fidel Castro's personal headquarters. The house was a thousand yards from the front at the village of Jiguani, sixty-five miles west along the Central Highway west of Santiago.

Whenever I walked the jungle paths up to the headquarters by myself, I wanted Castro's notoriously trigger-happy body guards to know who I was even if I couldn't identify myself to them in their language. So as soon as I came within range I started in singing-in as high a soprano as I could manage-From the halls of Montezuma . . . The combination of voice and tune should spell "American woman" in any tongue. Apparently it did for I wasn't actually fired on and not all Castro's visitors were that lucky.

The first morning in the command post cave I witnessed a "touching" family reunion.

Raul and Fidel Castro, Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

Months before, Fidel had sent off his younger brother Raul into the territory north of the Central Highway which was then under tight Batistiano control. It was said that giving Raul this mission was the hostile act of an older brother to a troublesome younger one, that Fidel meant Raul to fail and even die. But Raul had been careful to take with him three battalions of rebel infantry, including Major Lusson's which I had known at La Maya. And now in mid-December, Raul was returning in triumph to his older brother to report that but for a few city strongholds, all Oriente Province from the main road to the north coast of Cuba had been wrested by his forces from Batista's men. In military language, the Castro front at last was consolidated across the Central Highway.

So whatever differences had existed between the brothers were buried and everyone was jubilant. Fidel, tremendous in wet and muddy fatigues, laughed deeply as he swung back and forth in a hammock. Raul spoke shrilly and incessantly of his victories. Celia Sanchez, the woman who had been at Fidel's side for several years, hovered there now, thin and febrile in her green twill uniform with five gold religious medals swinging on chains around her neck. Vilma Espin, later to become Mrs. Raul Castro, smiled upon the company as she toyed with a new Belgian submachine gun presented to her as a token of Raul's triumphs.

In the background, but with their smiles a benediction, were two short handsome men old enough to have heavy gray in their combed beards-Hubert Matos and Eduardo Chibas, a one-time judge and a one-time lawyer now both infantry captains like their fellow-intellectual, Capitano Orlando. (To date according to the reports, Matos has been executed, Chibas is in exile and Orlando is missing.)

The normal scene in Castro's command post was less genial than my first impression but never less frenetic. Typically, it was a shifting knot of bearded officers and ragged messengers. The longer the beard, the longer its wearer had been a rebel.

The staccato rhythm of the hasty conferences, as orders were sent out and messages received, was puctuated by radio transmissions. These usually were spoken by Castro himself. He would grasp the walkie-talkie as if it were an enemy's throat and, in a voice to rouse the countryside, begin, "Urgente, urgente!" He never spoke in any kind of code and much of Cuba could follow the battles by simply tuning in on the Castro tactical transmissions.

The emotional tension around him rarely lessened; lie conveyed high pressure in every movement and was never still. His normal state of ease was a purposeful forty-inch stride forward, then back (it was nearly impossible to photograph him). His speaking voice was surprisingly soft and his incessant speech distinct. His manner of giving praise was a bear hug, his encouragement a heavy hand on the shoulder, his criticism an earthquake loss of temper. He reacted with Gargantuan anger to every report of dead and wounded; I considered this evidence that lie had never suffered the magnitude of losses Batista claimed. Once, when nine of his men lead been killed at Jiguani in a single action, he insisted I go out to make close-ups of each body "so their martyrdom will not be forgotten by the world."

The overwhelming fault in his character was plain for all to see even then. This was his inability to tolerate the absence of an enemy; he had to stand-or better, rant and shout-against some challenge every waking moment. His best tactical officers used this vast appetite for hostility to their own gain. A commander who needed fresh ammunition, for instance, could be sure he would get it not by making a reasonable request but by charging up to his commander, standing rock steady and shouting up at the great bearded face, "Dr. Fidel, I tell you you have been a fool not to support me! You should have known I needed more shells!"

Dead Revolutionary Soldier, Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

Like everyone else in the headquarters, I soon found my own manners conforming. If I'd heard a rumor of a jeep heading for the front but could not find it, I'd rail at any bearded officer that I was tired of having Cubans lie to me; where the devil was my jeep? Neither my illogic nor my untruthfulness mattered. Since my sincerity had been attested by my apparent Latin loss of temper, someone would go looking for a jeep.

That this twist of farce would someday lead to political tragedy-that the Reds would make of Castro's need for a powerful enemy a means of infiltrating his government, inspiring him to rattle their rockets against America long after Batista was gone-this I did not guess. Only its pathological overtones were plain.

In the rare times when he spoke quietly, Castro revealed a fine incisive mind utterly ill-matching the psychopathic temperament which subdued it. He liked to boast of his encyclopedic knowledge of the Batistiano soldiers. He said his secret weapon lay in his enemies' minds; they did not want to risk themselves for what they presumably were sworn to defend-the regime of Batista.

Every action I had seen bore out this thesis. Batista's men began by standing fast or moving out briskly until the first rebel bullets struck among them. Then came the critical moment, the military "moment of truth." Should they keep moving under fire long enough to open up with their superior weapons, take minor losses and almost certainly win the action? Or should they drop their arms, abandon their vehicles and flee-losing the battle unfought but surely saving every individual one of their own skins?

By all the military theory since Hannibal, Batista's men still held the advantage. If machinery won wars, they would have been victorious, for the rebelde faced strafing planes and armored cars with rifles and light machine guns. But the bearded ones made up their adversaries' minds with an unfaltering hail of lead. I had watched them keep on firing regardless of hazard till there was nothing left to shoot at. This was the one tactic Castro had seen they were prepared to use, and they had mastered it.

The final blow to any Batistiano's will to fight was the way in which Castro handled prisoners of war. When he was done with them he did not need to feed or bury them. They remained a problem only to Batista; they had been unfitted to fight, certainly to fight against Castro again.

Before I left the United States, the underground had briefed me on this tactic. "Fidel returns prisoners without intimidating them. We do not exchange them, you understand; not one of ours has ever been returned. But we disarm our enemies when we capture them and send them back home through the Cuban Red Cross."

I had been cynical about this claim. Near La Maya one afternoon I remarked to one of Castro's company commanders that I would be much surprised to see unintimidated, unwounded prisoners being returned in the middle of a shooting war. This remark was a mistake.

The next day I watched the surrender of the soldiers from the cuartel. The prisoners were gathered within a hollow square of rebel submachine gunners and harangued in the twilight by Raul.

"We hope that you will stay with us and fight against the master who has so ill-used you. If you decide to refuse this invitation-and I am not going to repeat it-you will be delivered to the custody of the Cuban Red Cross tomorrow. Once you are under Batista's orders again, we hope that you will not take up arms against us. But if you do, remember this-

"We took you this time. We can take you again. And when we do, we will not frighten or torture or kill you, any more than we are frightening you in this moment. If you are captured a second or even a third time we will again return you exactly as we are doing now."

This expression of utter contempt for the fighting potential of the defeated had an almost physical impact. Some actually flinched as they listened.

Children and Soldiers in Street, Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

The following noon, I could not question that these men were returned unharmed. One of Castro's lieutenants handed me a pencil and notebook as I came up to cover the delivery of the prisoners to the Red Cross.

"You count them for us, Americana," he said. There were 242, and I watched them ride away toward Santiago in trucks and busses bearing the cross markings on their canvas sides.

Thus Castro, in the name of humanitarianism, was able to inflict on his enemies the worst fate he could imagine for himself-the deprivation of emnity.

Two days before Christmas, 1958, a report reached the Castro command post that the Central Highway, from the village of Jiguani where fighting continued, almost back to Santiago where I wanted to return, now lay in rebelde hands. All sixty-five miles of it. I was to go along on the jeep patrol whose mission it was to make certain the road lay clear of Batistianos.

With two scouts, one of whom spoke pidgin-English, I left just after sundown. We broke the trip for a few hours sleep in a company command post-a deserted farm-just before dawn. At sunrise, as we drew up to a blown-out bridge, the rebels on post there told us this was the end of the liberated highway stretch. I'd have to walk the last twelve miles into Santiago but I had all day to do it in. The scouts walked me through a cane field to another little farmhouse and dropped me off, reminding me it was time to change my clothes.

The two families who shared the house had not left, in spite of the rifle fire we could hear crackling from the far side of a ridge. The women showed me into the bedroom and smiling, they brought a big white basin of water and a small green piece of soap. I washed and was ready to assume a new identity.

I took off the dirty blue-green shirt and muddy cotton slacks I'd worn for the last few weeks. Out of my one piece of baggage-a plaid canvas zipper bag-I pulled the white shirt saved for just this moment and my one remaining pair of slacks, beige and tourist-type. One of the women brought me some bright red shoe polish and with an old T-shirt, I made my limp oxfords gleam. At the back of my head I pinned a red hair ribbon with a big bow so it would perch jauntily on my bun.

I'd walked into their farmhouse a soldier-type female with dirty fatigues, long hair in a pony tail, and a grimy suntan. I walked out a typically groomed tourist with a spotless blouse, brushed hair high under a bow, vividly made up, wearing shoes with a mirror shine. Now when I ran up against the nearest of Batista's people, they wouldn't know where I had come from.

My guide for the twelve-mile walk was to be a sturdy thirteen-year-old boy named Carlos; the scouts told me he would show me the paths into Santiago and carry my bag. I demurred at parting from it; it contained my precious exposed film. But would a tourist lady carry her own luggage? My guide evidently thought not.

Soldiers with Wreckage, Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

So Carlos and I set out down a winding mud road that ran along a range of green hills just west of the shooting. It was shaded by drooping willow trees, and the late morning sunlight flickered through the branches.

Carlos was unimpressed by the sound of the rifle fire; he even whistled as we walked. If we were trying not to attract Batistiano attention so soon, though, I didn't think much of his choice of tune. It was the Castro revolutionaries' hymn.

In half an hour, the noise of firing had almost died away behind us. But there was a new noise. A jeep. We stood somewhat fearfully waiting for it to appear. In a few minutes it pulled up alongside us, the 26th of July insignia painted across the hood. A bearded captain stepped out and extended his hand to me. He spoke fluent English and said he knew who I was. "I am distressed that you are walking after you were so severely wounded at Maffo," he began in courtly fashion (I still had a deep limp). I told him I had not exactly been wounded, that I'd fallen victim to a Castro jeep and not a Batista shell.

He did not think my joke very funny and solemnly said he would take me a few miles nearer the city. Carlos and I both boarded the jeep and shortly were joined in the back seat by a rifleman and a girl in rebel uniform who suddenly appeared out of a cane field.

We rocked along a little farther until Carlos cried shrilly, "Avion! Venti-seis!" Airplane. Twenty-six, the B-26. We looked up and all of us exploded out of the braking jeep. The familiar silhouette was turning overhead to make a strafing run.

There was no ditch but only a long bush-covered embankment and we spilled down after the captain. He seemed to have spotted some cover off to one side. As I started to run I missed my plaid bag with the film; it had been resting across Carlos' knees in the jeep. Now it was rolling endover-end down the embankment ahead of me. It came to rest a dozen yards inside a plowed field.

I glanced at the strafing plane. I decided we hadn't been its target after all, and the jeep (which might still be a prime target) was nowhere to be seen. The plane seemed to have started a run on the next valley.

Almost leisurely I limped into the field and picked up my bag. The plaid would have been glaringly conspicuous from the air and I felt lucky to have retrieved it before the B-26 gunner noticed I was the only sign of human movement around.

But the B-26 hadn't been quite so committed to that farther target. It was circling now to line up with our road. This was about the same as lining up with me from my point of view. I needed concealment fast-but I'd lost sight of the rest of the party who presumably had found some.

Almost at my feet was a deep dry ditch choked with broadleaved weeds. All I had to do was roll into the ditch and the leaves would close over me again and ...

I lay flat in the ditch bottom, drawing a deep breath as I clutched my plaid bag. As the B-26 started to bore in, the thought burst on me that I wasn't wearing that old bluegreen shirt that had blended with leaves. I was wearing a blazing white one. If the sun could reach me through the leaves above-and it was doing just that-the leaves wouldn't hide the shirt from the B-26 gunner. This was the third time I'd misjudged a strafing run since I'd come to Cuba. Had the other two used up all the luck a nearsighted reporter could be expected to have? It would be too bitter to be hit now, on my way out!

The shells from the plane's pass struck the road, then the embankment-and stopped. While the bomber was pulling up, I knew I ought to try to improve my position. But how?

I heard a shout. "Here! Run now and you can make it!"

Havana Parade, Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

It was the captain. He was calling from a deep concrete culvert under the road. By lying flat and shoving close together, all of us complete with the men's weapons and my film were out of reach of the strafer's bullets.

We waited almost an hour before the plane disappeared. After we climbed stiffly from the culvert, the captain said he'd have to wait till after dark before he tried to use the road again. "And you-" addressing me-"might just as well go back to walking even if you are-uh, wounded." I agreed and we shook hands.

Four hours later with Carlos still beside me whistling the revolutionaries' hymn, we had hiked through sideroads into a suburb of Santiago. I made a present to the boy of half a dozen rolls of unexposed film. He grinned up at me from underneath his curly forelock as if this were more than he expected, and turned to go back the way we'd come. Then I hailed a cruising taxicab like any other footsore tourist.

Once I leaned back in it, I had a moment of pure panic. I couldn't remember the name of the motel across the city where I'd been told to report to the Castro underground. But I thought I could direct the cab to the general locality. There was something I wanted to see on the way even if it did mean a little detour.

"Take me slowly past the American Consulate," I told the driver.

He did and there, against the deepening afternoon blue of the tropic sky, the flag of the United States was fluttering in a gentle breeze.

In less than two years after Fidel Castro took over in Cuba, lie had carved out a historic niche almost big enough to fit his image of himself.

Bloodshed in Cuba has only just begun. I know grimly that this is one story of violence about which I will be writing for the rest of my life as a reporter. Probably I will again run for cover, see bullets strike, hear the sound of hurting people on the island.

See original source: Dickey Chapelle. What's A Woman Doing Here?: A Reporter's Report on Herself. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1962, pages 254-278.