Gina B. Nahai, born in Iran and educated in Switzerland and the United States, is the author of the award-winning novel Cry of the Peacock. A frequent lecturer on Iranian Jewish history and the topic of exile, she has studied the politics of Iran for the U.S. Department of Defense. Currently teaching fiction writing at the University of Southern California's Master of Professional Writing program, Ms. Nahai lives with her family in Los Angeles.

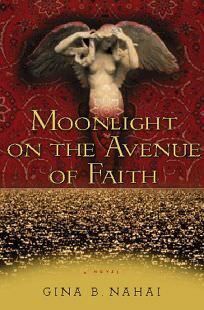

Excerpt from Moonlight on the Avenue of Faith

Nahai, Gina. Moonlight on the Avenue of Faith (Washington Square Press, 2000).

She was born in 1938, the daughter of Shusha the Beautiful and her tailor husband, Rahman the Ruler. Her family lived in two rooms they rented from Shusha's mother -- the terrible and terrifying BeeBee, who owned three houses in the Jewish ghetto of Tehran and who rented them room by room to anyone desperate enough to put up with her unreasonable demands and Draconian rules. BeeBee made no exception for her own daughter, and many were those in the ghetto who quietly whispered that she had never forgiven Shusha even a week's rent.

The rooms were unpaved and windowless, constructed of mud and clay and connected to the courtyard by a narrow wooden door made of loose planks nailed together into a lopsided, squeaky shape. The first room was where Shusha slept with her husband, and where he worked as a tailor during the day. The second room served as the family's dining and living room, and as the children's bedroom.

The children slept next to each other on the floor -- five small bodies stretched out under a single comforter, limbs intertwined and skin so accustomed to the warmth of others, not one of them could have fallen asleep in a bed by themselves.

Once, when she was three years old, Roxanna awoke to a strange scent. She sat up on the sheet spread over the thin canvas rug that covered the dirt floor and that served as the only barrier between her and the insects that crawled in the dust. She was a tiny child, so thin and light her movement never disturbed anyone else. She reached over and awakened Miriam.

"I dreamt I was a bird," she said.

Miriam sighed and turned over. She was nine years old and had been caring for her younger siblings all her life.

"Does something hurt?" she asked without opening her eyes.

"No. But I can't feel my legs."

Miriam felt Roxanna's forehead.

"You're not warm," she concluded. "Go back to sleep."

An hour later, Miriam woke up scared. She saw that Roxanna was in her own place. The other children were also sleeping. But the room, she realized, smelled strange: instead of the usual scent of skin and hair, of leftover food and old clothes and dry, unforgiving earth, Miriam the Moon smelled the sea.

She lit a candle and looked around. Nothing appeared out of place. Then she saw Roxanna: her hair was wet, her arms stretched to her sides, and she was afloat in a bed of white feathers.

Roxanna looked so calm and beautiful then, so immersed in her dreams of faraway mountains and emerald seas, that Miriam thought she would die if anyone awakened her. So she lay next to her, on that bed of feathers so white they looked almost blue in the moonlight, and hoped to dream her dreams.

Miriam saw the feathers many more times, smelled the Caspian so often in their city thousands of miles away from the sea, she thought some nights Roxanna was going to drown. Afraid of what would happen if anyone discovered the feathers, Miriam hid them inside the comforter. She split the seam open with her fingers and stuffed the feathers on top of the existing fill of cotton that was yellowed with age and thinned from use. But after a while the weight of Roxanna's secret became too heavy for Miriam to bear alone. Once, when the air in their room had become so humid it had turned into beads of moisture and was dripping off the roof onto the children's faces and hair, Miriam went to call her mother.

Shusha came barefoot and sleepy, her chador wrapped loosely around her waist, and for a moment stood above Roxanna without noticing the feathers.

"Look!" Miriam grabbed a fistful and held them close to Shusha's face. "Many nights I wake up and find these in her bed."

Shusha gasped as if she had been struck by lightning. Her body shook, only once, but with enough force that Miriam had to pull away from the impact. She saw the color run out of Shusha till her skin was transparent.

"Who else knows about this?" Shusha asked.

"No one." Miriam wished she had not called her. "I've been hiding them. I'm sure no one has a clue."

Just then Tala'at, Shusha's second daughter, stirred in her sleep. She ran her hand over her neck and chest, rubbing the sweat off her skin as she whispered hoarsely to an imaginary lover. She was only eight years old and had never had any contact with men outside her immediate family. But even then she was driven by lust, by the raw, uncompromised passion that would rule her adult life.

Shusha looked away from Tala'at and went outside. She sat on the steps that led from the bedroom down into the courtyard, then signaled for Miriam to sit next to her. She was a stunning woman -- dark skinned and dark eyed and so hauntingly beautiful she created a sense of confusion and sadness in anyone who saw her unveiled. But she had always seemed unaware, or perhaps ashamed, of her own beauty.

"Do you understand you can't tell anyone about the feathers?" she asked Miriam.

Miriam nodded.

"Do you know where they come from?"

Miriam began to answer, then stopped. They lived under a veil of silence then, a web of secrets spread over a thousand years, nurtured by a reverence for the power of the spoken word and a fear of its consequences. So Miriam did not speak, and Shusha did not tell Miriam what she knew so well: that the feathers in Roxanna's bed came from her dreams, that in them Roxanna was flying like a bird, or an angel, over a sea that was vast and limitless and that led her away from the tight borders of their ghetto, that the wings and the sea air spilled over the edge of the night sometimes, skipping the line between desire and truth, and poured into Roxanna's bed to speak of her longings.

← Go back Next page →