The population of Iran has historically been between 98 and 99 percent Muslim, of which the dominant portion, some 89 percent of total Muslims, have been Shi'a, the rest being Sunni (mostly Turkomans, Arabs, Baluchis, and Kurds living in the southwest, southeast, and northwest). Baha'i, Christian, Zoroastrian, and Jewish communities have constituted between 1 and 2 percent of the population. Sufi brotherhoods were popular, but there are no reliable statistics on their number. All religious minorities suffer varying degrees of officially sanctioned discrimination, particularly in the areas of employment, education, and housing.

The post-revolution government in Iran restricted freedom of religion. The Constitution declared that the "official religion of Iran is Islam and the sect followed is that of Ja'fari (Twelver) Shi'ism," and that this principle was "eternally immutable." Article 144 of the Constitution stated that "the Army of the Islamic Republic of Iran must be an Islamic army...committed to an Islamic ideology," and must "recruit into its service individuals who have faith in the objectives of the Islamic Revolution and are devoted to the cause of achieving its goals." However, members of religious minority communities sometimes served in the military. It also stated that "other Islamic denominations are to be accorded full respect," and recognizes Zoroastrians, Christians, and Jews, the country's pre-Islamic religions, as the only "protected religious minorities."

Religions not specifically protected under the Constitution did not enjoy freedom of religion. Members of the country's religious minorities, including Baha'is, Jews, Christians, and Sufi Muslims reported imprisonment, harassment, and intimidation based on their religious beliefs. This situation most directly affected the nearly 350,000 followers of the Baha'i Faith, who effectively had no legal rights either as individuals or as a community.

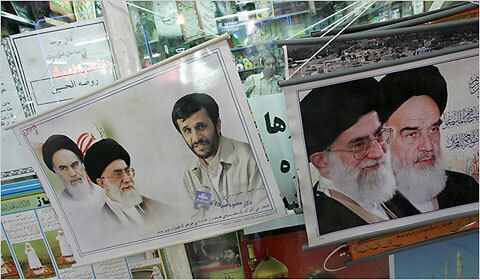

The central feature of the country's Islamic republican system was rule by a "religious jurisconsult." Its senior leadership, including the Supreme Leader of the Revolution, the President, the head of the Judiciary, and the Speaker of the Islamic Consultative Assembly (Parliament) was historically composed principally of Shi'a clergymen.

Religious activity was monitored closely by the Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS). Adherents of recognized religious minorities were not required to register individually with the Government. However, their community, religious, and cultural organizations, as well as schools and public events, were monitored closely. Baha'is were not recognized by the Government as a legitimate religious community. They are considered heretics by both Shi'a and Sunni Islam, and in Iran have been treated as belonging to an outlawed political organization. Registration of Baha'is was a police function. Similarly, Evangelical Christian groups were pressured by government authorities to compile and hand over membership lists for their congregations. Evangelicals have often resisted this demand.

The primacy of Islam affects all sectors of society. For example, non-Muslim owners of grocery shops were required to indicate their religious affiliation on the fronts of their shops. Individuals of all religions are required to observe Islamic codes on dress and gender segregation in public. Individuals of minority religions are prohibited from serving in senior administrative positions in many government ministries.

The government generally allowed recognized religious minorities to conduct religious education of their adherents, although it restricted this right considerably in some cases. Members of religious minorities were allowed to vote, but they could not run for President.

Iran also contains Shia sects that many of the Twelver Shia clergy regard as heretical. One of these is the Ismaili, a sect that has several thousand adherents living primarily in northeastern Iran. The Ismailis, of whom there were once several different sects, trace their origins to the son of Ismail who predeceased his father, the Sixth Imam. The Ismailis were very numerous and active in Iran from the eleventh to the thirteenth century. They were known in history as the "Assassins" because of their practice of killing political opponents. The Mongols destroyed their center at Alamut in the Alborz Mountains in 1256. Subsequently, their living imams went into hiding from non-Ismailis. In the nineteenth century, their leader emerged in public as the Agha Khan and fled to British-controlled India, where he supervised the revitalization of the sect. The majority of the several million Ismailis in the 1980s lived outside Iran.

Sunni Muslims constitute approximately 8 to 9 percent of the Iranian population. A majority of Kurds, virtually all Baluchis and Turkomans, and a minority of Arabs in Iran were Sunnis, as are small communities of Persians in southern Iran and Khorasan. The main difference between Sunnis and Shias is that the former do not accept the doctrine of the Imamate. Generally speaking, Iranian Shias are inclined to recognize Sunnis as fellow Muslims, but as those whose religion is incomplete. Shia clergy tend to view missionary work among Sunnis to convert them to true Islam as a worthwhile religious endeavor. Since the Sunnis generally live in the border regions of the country, there had been little occasion for Shia-Sunni conflict in most of Iran. In those towns with mixed populations in West Azarbaijan, the Persian Gulf region, and Baluchestan va Sistan, tensions between Shias and Sunnis existed both before and after the Revolution. Religious tensions have been highest during major Shia observances, especially Moharram.

Source: http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/iran/religion.htm

← Go back Next page →