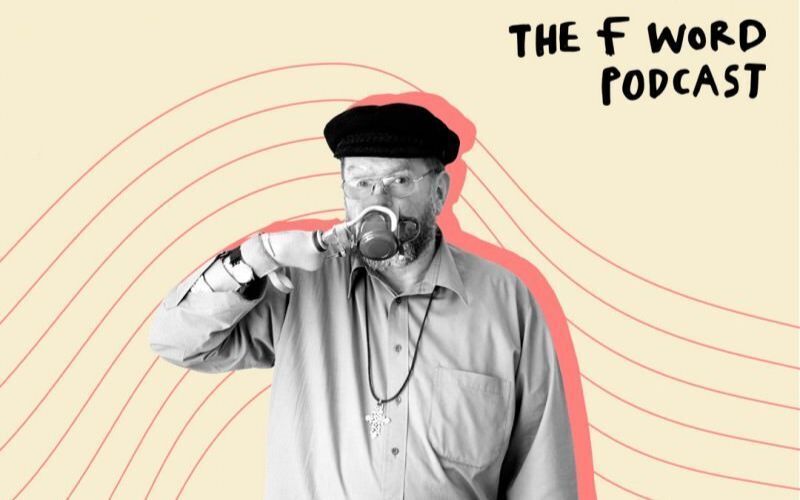

with Father Michael Lapsley

Date: January 31st, at any time

Listen to the Episode

The F Word Podcast examines the complex, messy, gripping subject of forgiveness.

In each episode Marina Cantacuzino, a journalist and founder of The Forgiveness Project, a Charter for Compassion partner, talks to a guest who despite having experienced great pain or trauma in their life has found a way through.

Some have forgiven those who’ve harmed them, others are grappling with forgiving themselves. Not everyone is able to forgive. Not everyone has made complete peace with their past.

But all those featured on the show display a strength that has grown out of vulnerability, and they all bear witness to the human search for meaning.

Conversation with Father Michael Lapsley

Marina Cantacuzino talks to Father Michael Lapsley, an Anglican priest, social justice activist and founder of the Institute for Healing of Memories in Cape Town. In 1990 at the height of the apartheid repression, Fr Michael received a letter bomb in the post in which he lost both his hands and one eye. He has been on a healing journey ever since.

More Background on Father Lapsley

After Father Michael Lapsley was exiled by the South African Government in 1976, he joined the African National Congress (ANC) and became one of their chaplains. Whilst living in Zimbabwe he discovered he was on the South African Government hit list. In April 1990 he received a letter bomb in the post.

No one told me why I was being exiled. But as a university chaplain, and in the wake of the Soweto uprising (when students were being detained and tortured) I was no friend to the apartheid regime. In exile I therefore became a target of the South African government.

I had long ago concluded that there was no road to freedom except via the route of self-sacrifice, but nothing could have prepared me for what was to follow. Three months after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison, I received a letter bomb hidden inside the pages of two religious magazines that had been posted from South Africa. In the bomb blast I lost both hands, one eye and had my eardrums shattered.

For the first three months I was as helpless as a newborn baby. People have asked me how I survived, and my only answer is that somehow, in the midst of the bombing, I felt that God was present. I also received so many messages of love and support from around the world that I was able to make my bombing redemptive – to bring life out of death, good out of evil.

Quite early on after the bomb I realized that if I was filled with hatred and desire for revenge, I’d be a victim forever. If we have something done to us, we are victims. If we physically survive, we are survivors. Sadly, many people never travel any further than this. I did travel further, going from victim to survivor, to victor. To become a victor is to move from being an object of history to become a subject once more. That is not to say that I will not always grieve what I’ve lost, because I will permanently bear the marks of disfigurement. Yet I believe I’ve gained through this experience. I realize that I can be more of a priest with no hands than with two hands.

In 1992, I returned to South Africa to find a nation of survivors, but a damaged nation. Everyone had a story – a truth – to tell. In my work I’ve developed a program called the Healing of Memories. Our workshops explore the effects of South Africa’s past at an emotional, psychological, and spiritual level. I try to support those who have suffered as they struggle to have their stories recognized.

I haven’t forgiven anyone because I have no one to forgive. No one was charged with this crime, and so for me forgiveness is still an abstract concept. But if I knew that the people who sent my bomb were now in prison, then I’d happily unlock the gates – although I’d like to know that they weren’t going to make any more bombs. I believe in restorative justice, and I believe in reparation. So, my attitude to the perpetrator is this: I’ll forgive them, but since I’ll never get my hands back, and will therefore always need someone to help me, they should pay that person’s wages. Not as a condition of forgiveness, but as part of reparation and restitution.