The Myth of Religious Violence

by Karen Armstrong

As we watch the fighters of the Islamic State (Isis) rampaging through the Middle East, tearing apart the modern nation-states of Syria and Iraq created by departing European colonialists, it may be difficult to believe we are living in the 21st century. The sight of throngs of terrified refugees and the savage and indiscriminate violence is all too reminiscent of barbarian tribes sweeping away the Roman empire, or the Mongol hordes of Genghis Khan cutting a swath through China, Anatolia, Russia and eastern Europe, devastating entire cities and massacring their inhabitants. Only the wearily familiar pictures of bombs falling yet again on Middle Eastern cities and towns – this time dropped by the United States and a few Arab allies – and the gloomy predictions that this may become another Vietnam, remind us that this is indeed a very modern war.

The ferocious cruelty of these jihadist fighters, quoting the Qur’an as they behead their hapless victims, raises another distinctly modern concern: the connection between religion and violence. The atrocities of Isis would seem to prove that Sam Harris, one of the loudest voices of the “New Atheism”, was right to claim that “most Muslims are utterly deranged by their religious faith”, and to conclude that “religion itself produces a perverse solidarity that we must find some way to undercut”. Many will agree with Richard Dawkins, who wrote in The God Delusion that “only religious faith is a strong enough force to motivate such utter madness in otherwise sane and decent people”. Even those who find these statements too extreme may still believe, instinctively, that there is a violent essence inherent in religion, which inevitably radicalises any conflict – because once combatants are convinced that God is on their side, compromise becomes impossible and cruelty knows no bounds.

Despite the valiant attempts by Barack Obama and David Cameron to insist that the lawless violence of Isis has nothing to do with Islam, many will disagree. They may also feel exasperated. In the west, we learned from bitter experience that the fanatical bigotry which religion seems always to unleash can only be contained by the creation of a liberal state that separates politics and religion. Never again, we believed, would these intolerant passions be allowed to intrude on political life. But why, oh why, have Muslims found it impossible to arrive at this logical solution to their current problems? Why do they cling with perverse obstinacy to the obviously bad idea of theocracy? Why, in short, have they been unable to enter the modern world? The answer must surely lie in their primitive and atavistic religion.

A Ukrainian soldier near the eastern Ukrainian town of Pervomaysk. Photo by Gleb Garanich/Reuters

But perhaps we should ask, instead, how it came about that we in the west developed our view of religion as a purely private pursuit, essentially separate from all other human activities, and especially distinct from politics. After all, warfare and violence have always been a feature of political life, and yet we alone drew the conclusion that separating the church from the state was a prerequisite for peace. Secularism has become so natural to us that we assume it emerged organically, as a necessary condition of any society’s progress into modernity. Yet it was in fact a distinct creation, which arose as a result of a peculiar concatenation of historical circumstances; we may be mistaken to assume that it would evolve in the same fashion in every culture in every part of the world.

We now take the secular state so much for granted that it is hard for us to appreciate its novelty, since before the modern period, there were no “secular” institutions and no “secular” states in our sense of the word. Their creation required the development of an entirely different understanding of religion, one that was unique to the modern west. No other culture has had anything remotely like it, and before the 18th century, it would have been incomprehensible even to European Catholics. The words in other languages that we translate as “religion” invariably refer to something vaguer, larger and more inclusive. The Arabic word din signifies an entire way of life, and the Sanskrit dharmacovers law, politics, and social institutions as well as piety. The Hebrew Bible has no abstract concept of “religion”; and the Talmudic rabbis would have found it impossible to define faith in a single word or formula, because the Talmud was expressly designed to bring the whole of human life into the ambit of the sacred. The Oxford Classical Dictionary firmly states: “No word in either Greek or Latin corresponds to the English ‘religion’ or ‘religious’.” In fact, the only tradition that satisfies the modern western criterion of religion as a purely private pursuit is Protestant Christianity, which, like our western view of “religion”, was also a creation of the early modern period.

Traditional spirituality did not urge people to retreat from political activity. The prophets of Israel had harsh words for those who assiduously observed the temple rituals but neglected the plight of the poor and oppressed. Jesus’s famous maxim to “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s” was not a plea for the separation of religion and politics. Nearly all the uprisings against Rome in first-century Palestine were inspired by the conviction that the Land of Israel and its produce belonged to God, so that there was, therefore, precious little to “give back” to Caesar. When Jesus overturned the money-changers’ tables in the temple, he was not demanding a more spiritualised religion. For 500 years, the temple had been an instrument of imperial control and the tribute for Rome was stored there. Hence for Jesus it was a “den of thieves”. The bedrock message of the Qur’an is that it is wrong to build a private fortune but good to share your wealth in order to create a just, egalitarian and decent society. Gandhi would have agreed that these were matters of sacred import: “Those who say that religion has nothing to do with politics do not know what religion means.”

The Myth of Religious Violence

Before the modern period, religion was not a separate activity, hermetically sealed off from all others; rather, it permeated all human undertakings, including economics, state-building, politics and warfare. Before 1700, it would have been impossible for people to say where, for example, “politics” ended and “religion” began. The Crusades were certainly inspired by religious passion but they were also deeply political: Pope Urban II let the knights of Christendom loose on the Muslim world to extend the power of the church eastwards and create a papal monarchy that would control Christian Europe. The Spanish inquisition was a deeply flawed attempt to secure the internal order of Spain after a divisive civil war, at a time when the nation feared an imminent attack by the Ottoman empire. Similarly, the European wars of religion and the thirty years war were certainly exacerbated by the sectarian quarrels of Protestants and Catholics, but their violence reflected the birth pangs of the modern nation-state.

It was these European wars, in the 16th and 17th centuries, that helped create what has been called “the myth of religious violence”. It was said that Protestants and Catholics were so inflamed by the theological passions of the Reformation that they butchered one another in senseless battles that killed 35% of the population of central Europe. Yet while there is no doubt that the participants certainly experienced these wars as a life-and-death religious struggle, this was also a conflict between two sets of state-builders: the princes of Germany and the other kings of Europe were battling against the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, and his ambition to establish a trans-European hegemony modelled after the Ottoman empire.

If the wars of religion had been solely motivated by sectarian bigotry, we should not expect to have found Protestants and Catholics fighting on the same side, yet in fact they often did so. Thus Catholic France repeatedly fought the Catholic Habsburgs, who were regularly supported by some of the Protestant princes. In the French wars of religion (1562–98) and the thirty years war, combatants crossed confessional lines so often that it was impossible to talk about solidly “Catholic” or “Protestant” populations. These wars were neither “all about religion” nor “all about politics”. Nor was it a question of the state simply “using” religion for political ends. There was as yet no coherent way to divide religious causes from social causes. People were fighting for different visions of society, but they would not, and could not, have distinguished between religious and temporal factors in these conflicts. Until the 18th century, dissociating the two would have been like trying to take the gin out of a cocktail.

By the end of the thirty years war, Europeans had fought off the danger of imperial rule. Henceforth Europe would be divided into smaller states, each claiming sovereign power in its own territory, each supported by a professional arms and governed by a prince who aspired to absolute rule – a recipe, perhaps, for chronic interstate warfare. New configurations of political power were beginning to force the church into a subordinate role, a process that involved a fundamental reallocation of authority and resources from the ecclesiastical establishment to the monarch. When the new word “secularisation” was coined in the late 16th century, it originally referred to “the transfer of goods from the possession of the church into that of the world”. This was a wholly new experiment. It was not a question of the west discovering a natural law; rather, secularisation was a contingent development. It took root in Europe in large part because it mirrored the new structures of power that were pushing the churches out of government.

These developments required a new understanding of religion. It was provided by Martin Luther, who was the first European to propose the separation of church and state. Medieval Catholicism had been an essentially communal faith; most people experienced the sacred by living in community. But for Luther, the Christian stood alone before his God, relying only upon his Bible. Luther’s acute sense of human sinfulness led him, in the early 16th century, to advocate the absolute states that would not become a political reality for another hundred years. For Luther, the state’s prime duty was to restrain its wicked subjects by force, “in the same way as a savage wild beast is bound with chains and ropes”. The sovereign, independent state reflected this vision of the independent and sovereign individual. Luther’s view of religion, as an essentially subjective and private quest over which the state had no jurisdiction, would be the foundation of the modern secular ideal.

But Luther’s response to the peasants’ war in Germany in 1525, during the early stages of the wars of religion, suggested that a secularised political theory would not necessarily be a force for peace or democracy. The peasants, who were resisting the centralising policies of the German princes – which deprived them of their traditional rights – were mercilessly slaughtered by the state. Luther believed that they had committed the cardinal sin of mixing religion and politics: suffering was their lot, and they should have turned the other cheek, and accepted the loss of their lives and property. “A worldly kingdom,” he insisted, “cannot exist without an inequality of persons, some being free, some imprisoned, some lords, some subjects.” So, Luther commanded the princes, “Let everyone who can, smite, slay and stab, secretly or openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisoned, hurtful, or devilish than a rebel.”

Dawn of the Liberal State

By the late 17th century, philosophers had devised a more urbane version of the secular ideal. For John Locke it had become self-evident that “the church itself is a thing absolutely separate and distinct from the commonwealth. The boundaries on both sides are fixed and immovable.” The separation of religion and politics – “perfectly and infinitely different from each other” – was, for Locke, written into the very nature of things. But the liberal state was a radical innovation, just as revolutionary as the market economy that was developing in the west and would shortly transform the world. Because of the violent passions it aroused, Locke insisted that the segregation of “religion” from government was “above all things necessary” for the creation of a peaceful society.

Hence Locke was adamant that the liberal state could tolerate neither Catholics nor Muslims, condemning their confusion of politics and religion as dangerously perverse. Locke was a major advocate of the theory of natural human rights, originally pioneered by the Renaissance humanists and given definition in the first draft of the American Declaration of Independence as life, liberty and property. But secularisation emerged at a time when Europe was beginning to colonise the New World, and it would come to exert considerable influence on the way the west viewed those it had colonised – much as in our own time, the prevailing secular ideology perceives Muslim societies that seem incapable of separating faith from politics to be irredeemably flawed.

This introduced an inconsistency, since for the Renaissance humanists there could be no question of extending these natural rights to the indigenous inhabitants of the New World. Indeed, these peoples could justly be penalised for failing to conform to European norms. In the 16th century, Alberico Gentili, a professor of civil law at Oxford, argued that land that had not been exploited agriculturally, as it was in Europe, was “empty” and that “the seizure of [such] vacant places” should be “regarded as law of nature”. Locke agreed that the native peoples had no right to life, liberty or property. The “kings” of America, he decreed, had no legal right of ownership to their territory. He also endorsed a master’s “Absolute, arbitrary, despotical power” over a slave, which included “the power to kill him at any time”. The pioneers of secularism seemed to be falling into the same old habits as their religious predecessors. Secularism was designed to create a peaceful world order, but the church was so intricately involved in the economic, political and cultural structures of society that the secular order could only be established with a measure of violence. In North America, where there was no entrenched aristocratic government, the disestablishment of the various churches could be accomplished with relative ease. But in France, the church could be dismantled only by an outright assault; far from being experienced as a natural and essentially normative arrangement, the separation of religion and politics could be experienced as traumatic and terrifying.

During the French revolution, one of the first acts of the new national assembly on November 2, 1789, was to confiscate all church property to pay off the national debt: secularisation involved dispossession, humiliation and marginalisation. This segued into outright violence during the September massacres of 1792, when the mob fell upon the jails of Paris and slaughtered between two and three thousand prisoners, many of them priests. Early in 1794, four revolutionary armies were dispatched from Paris to quell an uprising in the Vendée against the anti-Catholic policies of the regime. Their instructions were to spare no one. At the end of the campaign, General François-Joseph Westermann reportedly wrote to his superiors: “The Vendée no longer exists. I have crushed children beneath the hooves of our horses, and massacred the women … The roads are littered with corpses.”

Ironically, no sooner had the revolutionaries rid themselves of one religion, than they invented another. Their new gods were liberty, nature and the French nation, which they worshipped in elaborate festivals choreographed by the artist Jacques Louis David. The same year that the goddess of reason was enthroned on the high altar of Notre Dame cathedral, the reign of terror plunged the new nation into an irrational bloodbath, in which some 17,000 men, women and children were executed by the state.

To Die for One’s Country

When Napoleon’s armies invaded Prussia in 1807, the philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte similarly urged his countrymen to lay down their lives for the Fatherland – a manifestation of the divine and the repository of the spiritual essence of the Volk. If we define the sacred as that for which we are prepared to die, what Benedict Anderson called the “imagined community” of the nation had come to replace God. It is now considered admirable to die for your country, but not for your religion.

As the nation-state came into its own in the 19th century along with the industrial revolution, its citizens had to be bound tightly together and mobilised for industry. Modern communications enabled governments to create and propagate a national ethos, and allowed states to intrude into the lives of their citizens more than had ever been possible. Even if they spoke a different language from their rulers, subjects now belonged to the “nation,” whether they liked it or not. John Stuart Mill regarded this forcible integration as progress; it was surely better for a Breton, “the half-savage remnant of past times”, to become a French citizen than “sulk on his own rocks”. But in the late 19th century, the British historian Lord Acton feared that the adulation of the national spirit that laid such emphasis on ethnicity, culture and language, would penalise those who did not fit the national norm: “According, therefore, to the degree of humanity and civilisation in that dominant body which claims all the rights of the community, the inferior races are exterminated or reduced to servitude, or put in a condition of dependence.”

The Enlightenment philosophers had tried to counter the intolerance and bigotry that they associated with “religion” by promoting the equality of all human beings, together with democracy, human rights, and intellectual and political liberty, modern secular versions of ideals which had been promoted in a religious idiom in the past. The structural injustice of the agrarian state, however, had made it impossible to implement these ideals fully. The nation-state made these noble aspirations practical necessities. More and more people had to be drawn into the productive process and needed at least a modicum of education. Eventually they would demand the right to participate in the decisions of government. It was found by trial and error that those nations that democratised forged ahead economically, while those that confined the benefits of modernity to an elite fell behind. Innovation was essential to progress, so people had to be allowed to think freely, unconstrained by the constraints of their class, guild or church. Governments needed to exploit all their human resources, so outsiders, such as Jews in Europe and Catholics in England and America, were brought into the mainstream.

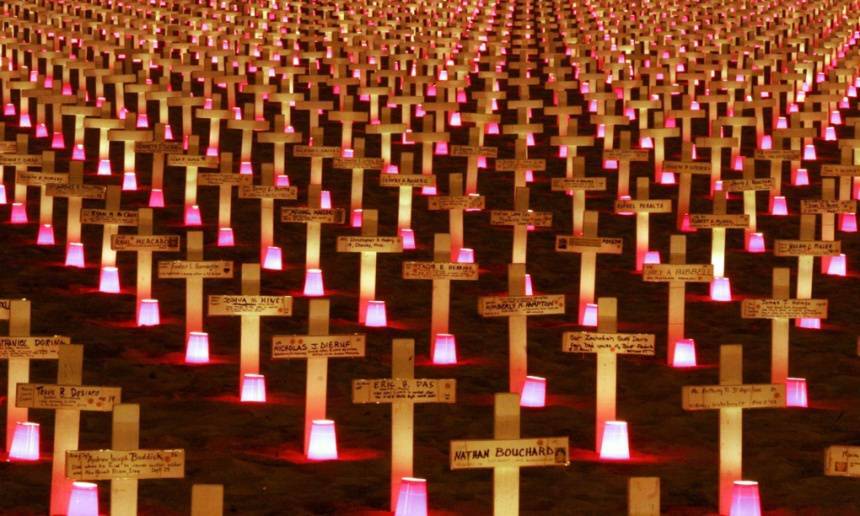

A candlelight vigil in 2007 at the Arlington West Memorial in Santa Barbara, California, to honour American soldiers killed in the Iraq war. Photo by Sipa Press/REX

Yet this toleration was only skin-deep, and as Lord Acton had predicted, an intolerance of ethnic and cultural minorities would become the achilles heel of the nation-state. Indeed, the ethnic minority would replace the heretic (who had usually been protesting against the social order) as the object of resentment in the new nation-state. Thomas Jefferson, one of the leading proponents of the Enlightenment in the United States, instructed his secretary of war in 1807 that Native Americans were “backward peoples” who must either be “exterminated” or driven “beyond our reach” to the other side of the Mississippi “with the beasts of the forest”. The following year, Napoleon issued the “infamous decrees”, ordering the Jews of France to take French names, privatise their faith, and ensure that at least one in three marriages per family was with a gentile. Increasingly, as national feeling became a supreme value, Jews would come to be seen as rootless and cosmopolitan. In the late 19th century, there was an explosion of antisemitism in Europe, which undoubtedly drew upon centuries of Christian prejudice, but gave it a scientific rationale, claiming that Jews did not fit the biological and genetic profile of the Volk, and should be eliminated from the body politic as modern medicine cut out a cancer.

When secularisation was implemented in the developing world, it was experienced as a profound disruption – just as it had originally been in Europe. Because it usually came with colonial rule, it was seen as a foreign import and rejected as profoundly unnatural. In almost every region of the world where secular governments have been established with a goal of separating religion and politics, a counter-cultural movement has developed in response, determined to bring religion back into public life. What we call “fundamentalism” has always existed in a symbiotic relationship with a secularisation that is experienced as cruel, violent and invasive. All too often an aggressive secularism has pushed religion into a violent riposte. Every fundamentalist movement that I have studied in Judaism, Christianity and Islam is rooted in a profound fear of annihilation, convinced that the liberal or secular establishment is determined to destroy their way of life. This has been tragically apparent in the Middle East.

Very often modernising rulers have embodied secularism at its very worst and have made it unpalatable to their subjects. Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who founded the secular republic of Turkey in 1918, is often admired in the west as an enlightened Muslim leader, but for many in the Middle East he epitomised the cruelty of secular nationalism. He hated Islam, describing it as a “putrefied corpse”, and suppressed it in Turkey by outlawing the Sufi orders and seizing their properties, closing down the madrasas and appropriating their income. He also abolished the beloved institution of the caliphate, which had long been a dead-letter politically but which symbolised a link with the Prophet. For groups such as al-Qaida and Isis, reversing this decision has become a paramount goal.

Ataturk also continued the policy of ethnic cleansing that had been initiated by the last Ottoman sultans; in an attempt to control the rising commercial classes, they systematically deported the Armenian and Greek-speaking Christians, who comprised 90% of the bourgeoisie. The Young Turks, who seized power in 1909, espoused the antireligious positivism associated with August Comte and were also determined to create a purely Turkic state. During the first world war, approximately one million Armenians were slaughtered in the first genocide of the 20th century: men and youths were killed where they stood, while women, children and the elderly were driven into the desert where they were raped, shot, starved, poisoned, suffocated or burned to death. Clearly inspired by the new scientific racism, Mehmet Resid, known as the “execution governor”, regarded the Armenians as “dangerous microbes” in “the bosom of the Fatherland”. Ataturk completed this racial purge. For centuries Muslims and Christians had lived together on both sides of the Aegean; Ataturk partitioned the region, deporting Greek Christians living in what is now Turkey to Greece, while Turkish-speaking Muslims in Greece were sent the other way.

The Fundamentalist Reaction

Secularising rulers such as Ataturk often wanted their countries to look modern, that is, European. In Iran in 1928, Reza Shah Pahlavi issued the laws of uniformity of dress: his soldiers tore off women’s veils with bayonets and ripped them to pieces in the street. In 1935, the police were ordered to open fire on a crowd who had staged a peaceful demonstration against the dress laws in one of the holiest shrines of Iran, killing hundreds of unarmed civilians. Policies like this made veiling, which has no Qur’anic endorsement, an emblem of Islamic authenticity in many parts of the Muslim world.

Following the example of the French, Egyptian rulers secularised by disempowering and impoverishing the clergy. Modernisation had begun in the Ottoman period under the governor Muhammad Ali, who starved the Islamic clergy financially, taking away their tax-exempt status, confiscating the religiously endowed properties that were their principal source of income, and systematically robbing them of any shred of power. When the reforming army officer Jamal Abdul Nasser came to power in 1952, he changed tack and turned the clergy into state officials. For centuries, they had acted as a protective bulwark between the people and the systemic violence of the state. Now Egyptians came to despise them as government lackeys. This policy would ultimately backfire, because it deprived the general population of learned guidance that was aware of the complexity of the Islamic tradition. Self-appointed freelancers, whose knowledge of Islam was limited, would step into the breach, often to disastrous effect.

If some Muslims today fight shy of secularism, it is not because they have been brainwashed by their faith but because they have often experienced efforts at secularisation in a particularly virulent form. Many regard the west’s devotion to the separation of religion and politics as incompatible with admired western ideals such as democracy and freedom. In 1992, a military coup in Algeria ousted a president who had promised democratic reforms, and imprisoned the leaders of the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS), which seemed certain to gain a majority in the forthcoming elections. Had the democratic process been thwarted in such an unconstitutional manner in Iran or Pakistan, there would have been worldwide outrage. But because an Islamic government had been blocked by the coup, there was jubilation in some quarters of the western press – as if this undemocratic action had instead made Algeria safe for democracy. In rather the same way, there was an almost audible sigh of relief in the west when the Muslim Brotherhood was ousted from power in Egypt last year. But there has been less attention to the violence of the secular military dictatorship that has replaced it, which has exceeded the abuses of the Mubarak regime.

After a bumpy beginning, secularism has undoubtedly been valuable to the west, but we would be wrong to regard it as a universal law. It emerged as a particular and unique feature of the historical process in Europe; it was an evolutionary adaptation to a very specific set of circumstances. In a different environment, modernity may well take other forms. Many secular thinkers now regard “religion” as inherently belligerent and intolerant, and an irrational, backward and violent “other” to the peaceable and humane liberal state – an attitude with an unfortunate echo of the colonialist view of indigenous peoples as hopelessly “primitive”, mired in their benighted religious beliefs. There are consequences to our failure to understand that our secularism, and its understanding of the role of religion, is exceptional. When secularisation has been applied by force, it has provoked a fundamentalist reaction – and history shows that fundamentalist movements which come under attack invariably grow even more extreme. The fruits of this error are on display across the Middle East: when we look with horror upon the travesty of Isis, we would be wise to acknowledge that its barbaric violence may be, at least in part, the offspring of policies guided by our disdain.

Karen Armstrong’s Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence is published by Bodley Head.

See article from source:

The Myth of Religious Violence