Where is the Love?

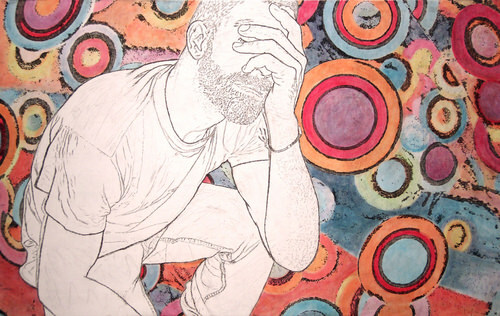

Image by John Edward Marin

When I’ve written recently about food stamp recipients, the uninsured and prison inmates, I’ve had plenty of pushback from readers.

A reader named Keith reflected a coruscating chorus when he protested: “If kids are going hungry, it is because of the parents not upholding their responsibilities.”

A reader in Washington bluntly suggested taking children from parents and putting them in orphanages.

Jim asked: “Why should I have to subsidize someone else’s child? How about personal responsibility? If you procreate, you provide.”

After a recent column about an uninsured man who delayed seeing a doctor about a condition that turned out to be colon cancer, many readers noted that he is a lifelong smoker and said he had it coming.

“What kind of a lame brain doofus is this guy?” one reader asked. “And like it’s our fault that he couldn’t afford to have himself checked out?”

Such scorn seems widespread, based on the comments I get on my blog and Facebook page — as well as on polling and on government policy. At root, these attitudes reflect a profound lack of empathy.

A Princeton University psychology professor, Susan Fiske, has found that when research subjects hooked up to neuro-imaging machines look at photos of the poor and homeless, their brains often react as if they are seeing things, not people. Her analysis suggests that Americans sometimes react to poverty not with sympathy but with revulsion.

So, on Thanksgiving, maybe we need a conversation about empathy for fellow humans in distress.

Let’s acknowledge one point made by these modern social Darwinists: It’s true that some people in poverty do suffer in part because of irresponsible behavior, from abuse of narcotics to criminality to laziness at school or jobs. But remember also that many of today’s poor are small children who have done nothing wrong.

Some 45 percent of food stamp recipients are children, for example. Do we really think that kids should go hungry if they have criminal parents? Should a little boy not get a curved spine treated properly because his dad is a deadbeat? Should a girl not be able to go to preschool because her mom is an alcoholic?

Successful people tend to see in themselves a simple narrative: You study hard, work long hours, obey the law and create your own good fortune. Well, yes. That often works fine in middle-class families.

But if you’re conceived by a teenage mom who drinks during pregnancy so that you’re born with fetal alcohol effects, the odds are overwhelmingly stacked against you from before birth. You’ll perhaps never get traction.

Likewise, if you’re born in a high-poverty neighborhood to a stressed-out single mom who doesn’t read to you and slaps you more than hugs you, you’ll face a huge handicap. One University of Minnesota study found that the kind of parenting a child receives in the first 3.5 years is a better predictor of high school graduation than I.Q.

All this helps explain why one of the strongest determinants of ending up poor is being born poor. As Warren Buffett puts it, our life outcomes often depend on the “ovarian lottery.” Sure, some people transcend their circumstances, but it’s callous for those born on second or third base to denounce the poor for failing to hit home runs.

John Rawls, the brilliant 20th-century philosopher, argued for a society that seems fair if we consider it from behind a “veil of ignorance” — meaning we don’t know whether we’ll be born to an investment banker or a teenage mom, in a leafy suburb or a gang-ridden inner city, healthy or disabled, smart or struggling, privileged or disadvantaged. That’s a shrewd analytical tool — and who among us would argue for food stamp cuts if we thought we might be among the hungry children?

As we celebrate Thanksgiving, let’s remember that the difference between being surrounded by a loving family or being homeless on the street is determined not just by our own level of virtue or self-discipline, but also by an inextricable mix of luck, biography, brain chemistry and genetics.

For those who are well-off, it may be easier to castigate the irresponsibility of the poor than to recognize that success in life is a reflection not only of enterprise and willpower, but also of random chance and early upbringing.

Low-income Americans, who actually encounter the needy in daily life, understand this complexity and respond with empathy. Researchers say that’s why the poorest 20 percent of Americans donate more to charity, as a fraction of their incomes, than the richest 20 percent. Meet those who need help, especially children, and you become less judgmental and more compassionate.

And compassion isn’t a sign of weakness, but a mark of civilization.

Nicholas Kristof, a columnist for The New York Times since 2001, writes op-ed columns that appear twice a week. Mr. Kristof won the Pulitzer Prize two times, in 1990 and 2006. In 2012, he was a Pulitzer finalist in Commentary for his 2011 columns that often focused on the disenfranchised in many parts of the world.

Mr. Kristof grew up on a sheep and cherry farm near Yamhill, Oregon. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Harvard College and then studied law at Oxford University on a Rhodes Scholarship, graduating with first class honors. He later studied Arabic in Cairo and Chinese in Taipei.

While working in France after high school, he caught the travel bug and began backpacking around Africa and Asia during his student years, writing articles to cover his expenses.

Mr. Kristof has lived on four continents, reported on six, and traveled to more than 150 countries, plus all 50 states, every Chinese province and every main Japanese island. He jokes that he’s one of the very few Americans to be at least a two-time visitor to every member of the so-called Axis of Evil. During his travels, he has had unpleasant experiences with malaria, mobs and an African airplane crash.

This article was originally posted on New York Times in 2013.