Photo by Ambrose Chua on Unsplash

There are three steps in Phase 1. Take your time with them. It is important to build a good solid structure when you are putting together an initiative. As you go through these building steps you are observing and interacting with your community, learning from different organizations and spreading out the ownership of your compassion initiative.

Step 1: Identify “discomforts” in your community—those issues that are causing pain and suffering to individuals or groups or the entire community—which can be addressed and relieved through compassionate action.

Perhaps you are part of your community’s local government, or you may work in social services or healthcare, and you have wished that something more could be done to resolve the difficulties facing people in your community—for example, the homeless, the isolated and depressed elderly, an immigrant population, or youth who are pressured to be part of a gang culture.

Maybe you work with the community’s youth as an educator, a counselor, or in recreational services, and you have recognized both the promise of youth as well as the difficulties they face in our rapidly changing world. Or, you may be a citizen who has deep concerns about the safety, the health, or the emotional well-being of other groups of community members—the disabled, orphaned or abandoned children, the mentally ill, or racial or ethnic groups who are confronted by discrimination.

You may be concerned about the transport of hazardous materials through your area, or about the increasing air pollution or the lack of clean water in your community. Or you may be an observer who has recognized other issues that cause suffering in your community. Perhaps you have been motivated by your concern to identify possible ways to relieve suffering—quality, affordable childcare; anti-bullying programs in schools; or compassionate care for veterans in your city or town or neighborhood.

All of these issues are what author Karen Armstrong means when she talks about those issues that are “uncomfortable” for a community and therefore in need of compassionate action in order to provide for the well-being of all community members.

One useful tool for beginning an evaluation in your community is the Compassionate Community Assessment.

Learn how to identify community assets and resources, and how to engage them in the community change effort.

Photo by Clemens van Lay, unsplash.com

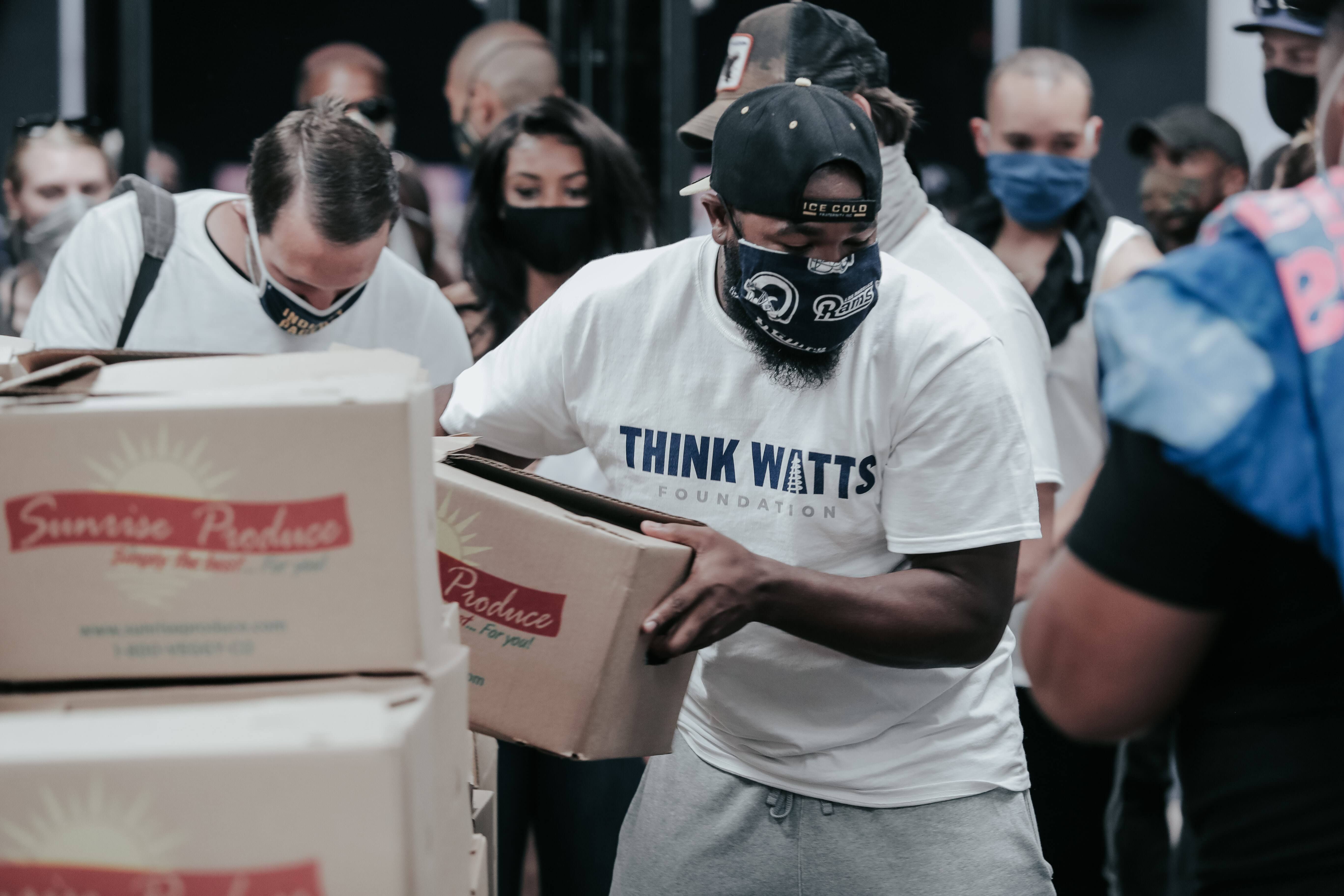

Step 2: Find out what is already being done, or has been done, to address issues in your community, learn what has worked and not worked, and, recognize and acknowledge those successes.

Even if you, as an individual, have already identified the major challenges and “discomforts” of your community, your initiative will benefit from some investigative work alongside others who care about the community. Discover who else is working to improve your community, and working to provide a place of well-being. Recognize and acknowledge that work, and invite those people to join you in creating a Compassionate Community. Key words here are: recognizing and appreciating work that has been and is being done.

The Dutch Compassion Movement in The Netherlands provides a wonderful example and model related to this step:

In the Dutch Compassion Movement, city and community initiatives and partners are all organized under one charity trust. First called Handvest voor Compassie and today has joined with another group. Early in its coming together, the organization decided to design a project to find out how various groups in the greater Amsterdam area were going about handling complex social issues. They wanted to produce a book to showcase how local problems were continually being handled and could result in providing the impetus for other groups to follow suit, locally and throughout the country. A similar project had been done the preceding year in another Dutch town, Gorinchem. They believed that this initial step would help identify issues that would eventually be part of a compassionate city campaign.

The Amsterdam project resulted in the publication of De Ander (meaning "The Other"), a book that recorded over 50 stories about how several social services organizations were dealing with complex issues, many of them arising from misunderstandings between Amsterdammers and newly arrived immigrants. Like many European countries, the Dutch have received large influxes of refugees from Eastern Europe and war-torn countries in Africa. In addition, in the 1960s, large numbers of Turks made The Netherlands their new home. Today a myriad of organizations and committees have sprung up to deal with problems that were not previously found in the country. De Ander presents heart-warming stories of conflict between families, neighbors and among ethnic groups. For example, it showcases the story of a group of medical students who are working to reform healthcare delivery processes, an education organization working to teach mediation skills to young people, ethnic groups dedicated to teaching children of immigrants the customs and language of their ethnic group and helping them function as being "in between" cultures.

More recently, Ann Horst, a Charter for Compassion partner, Small Biz San Antonio, has put together a directory in an effort to lift up and validate small businesses of all ethnicities, races, abilities/disabilities, sexual preferences, expressions, and gender identities.

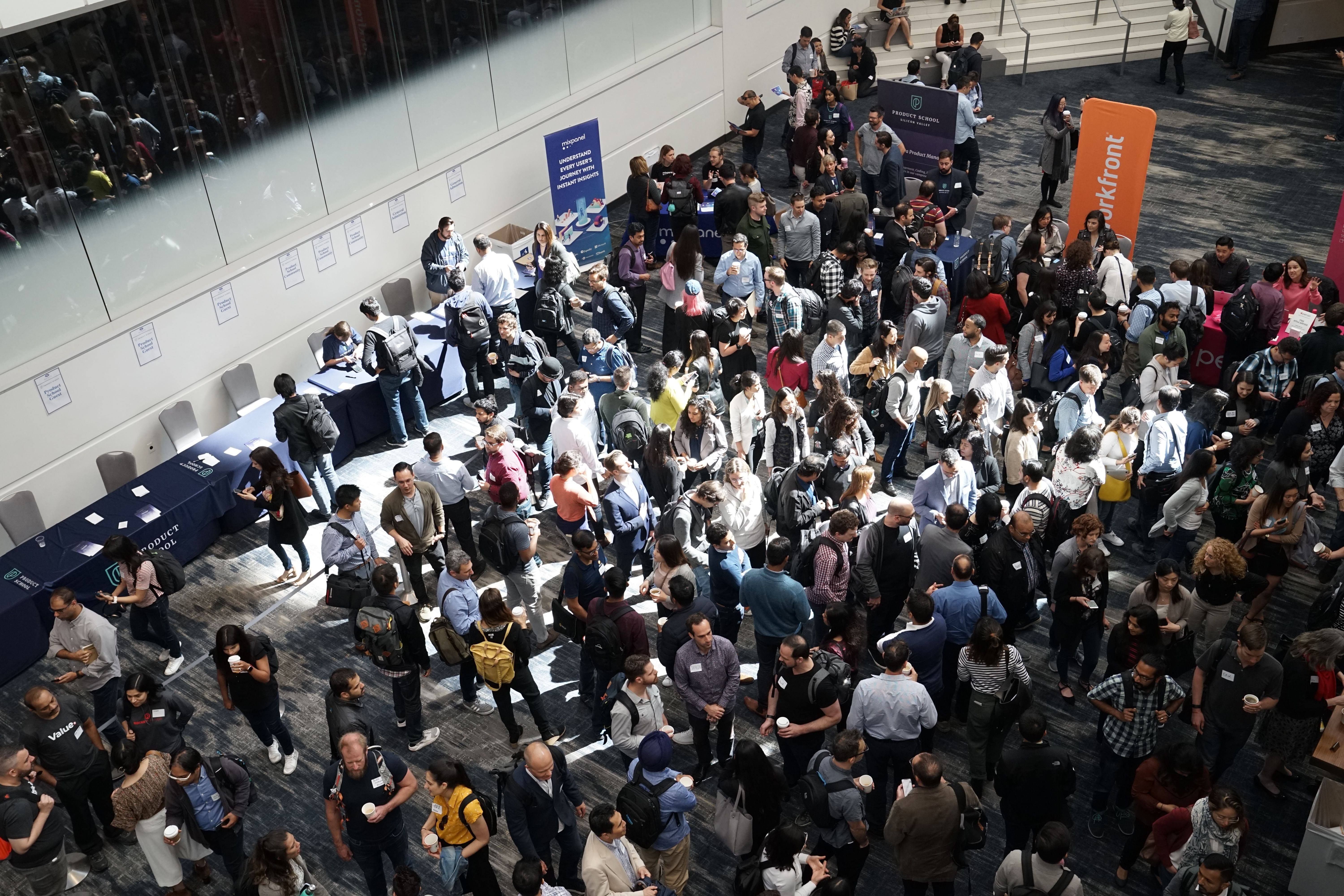

Step 3: Invite people to join you in assessing your community. Include community leaders as well as those informal leaders of other community constituencies that can give voice to the needs of the community.

During Phase One of creating a Compassionate Community, it may be helpful to bring together community leaders and influencers to discover, assess, and evaluate the community’s existing strengths as well as those challenges that need to be addressed. You may find people in formal leadership positions—for example, in local government or healthcare or education—who can make valuable contributions to your initiative or may already be addressing the issues you have identified. You may also invite more informal leaders, for example--those people who have influence in their neighborhoods, faith groups, or ethnic groups.

Together, you can discuss what it means for a community to take care of all community members—and to relieve pain and suffering wherever it exists in your community. You may find it useful to provide presentations that inform people about the community’s current opportunities and challenges. In a collaborative and inclusive discussion, you will gain a clearer picture of what is good about your community and where compassionate action is working—those will be strengths to build on--and together you can discover the issues that are causing pain and suffering to some individuals or groups—those are the places where the community is vulnerable and in need of compassionate action.

Each community will find its own way to explore how compassion can bring well-being to all community members. As one example, a young Pakistani journalist, Naween Mangi, started the Ali Hasan Mangi Memorial Trust in memory of her grandfather, whom she describes as “compulsively compassionate.” She explains:

The aim was to create a model village in his ancestral hometown of Khairo Dero, a village in southern Pakistan. A model that could be replicated elsewhere in turning poverty-stricken and forgotten rural hamlets into habitable places; complete with access to clean water, a sanitation network, housing for all, education, income-generating opportunities, and health-care services.

As we began the process of engaging the community of 3,700 people in their own development, something felt sorely amiss. While projects were doing well and impact was visible, the work seemed somehow to be standing in isolation. Then, I came across the Charter for Compassion, became a signatory, and started thinking about how we could bring compassion into village life, creating a binding force that would weave our work and our community together.

When we opened a community center and park we documented our symbolic commitment to practicing compassion by displaying the Charter in our Community Hall. We then started by teaching our trust’s employees and volunteers about compassion and seeking their views on how we can implement this approach in our daily lives.

Since we wanted to make compassion real, a part of village life, and a practice rather than a notion, we began holding regular activities exploring how to live compassionately. Some of the events we routinely host are:

Readings from Karen Armstrong’s Letter to Pakistan and Twelve Steps to a Compassionate Life.

Short plays developed and performed by village children on the theme of compassion.

Drawing competitions about compassion.

Compassion Counter: We maintain a journal at the Community Center where adults and children can come and record their acts of compassion. We’ve crossed 700 acts and are aiming to hit 1,000 in just a few months.. Two examples: a schoolboy took a few extra moments to clear away stones from the road so passengers wouldn’t be hurt and on a chilly January morning, and a teacher brought in one of her favorite sweaters for a person who didn’t have any warm clothes.

Compassionate Living Day: We celebrate this without schedule and as often as our community feels we need to center ourselves and come back to the mindful practice of compassion. The day is marked by cultural performances, plays and speeches on how we can treat fellow villagers as we would ourselves would like to be treated.”

Working with all Three Steps

Honestly speaking, the first three steps are the most involved and may well take you the longest to implement. In Step Three you are exploring, inviting and forming your expanding team. You are also seeing what works in your community and how you can build on accomplishments of the past. You are staying alert to the discomforts found in your community and attempting to think about them. By clicking on the box below, DETERMINING ISSUES, you will get a comprehensive view of all the issues to date that our compassionate initiatives across the globe are working on. We’ve tried to think of all the questions we could about each issue, categorized them and checked them out against the 17 Goals of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and other key documents.

The second box, COLLECTIVE IMPACT, reminds us that we need to be working with others to set the agenda, remain open to communication, guarantee that there is room at the table for everyone, that we stop periodically to reflect on our success and set backs.

Finally, the third box, INTEGRAL APPROACH is perhaps more theoretical than you may want to consider at this moment, but more than likely you will want to come back to this section and even expand on it. The Integral Approach helps you view yourself and the world around you in more comprehensive and effective ways. The philosopher, Ken Wilbur is very closely associated with the Integral approach. Barbara Marx Hubbard and Marilyn Hamilton are also aligned with Wilbur’s thinking. However, the Charter for Compassion is most involved with Marilyn Hamilton’s Integral City Model.