Photo: No Job for a Woman--Women World War II Correspondents

Georgette Louise Meyer (Dickey Chapelle) was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on 14th March 1919. After leaving Shorewood High School she briefly attended aeronautical design classes at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. According to her biographer: "She returned home a few months later, knowing she would rather fly a plane than design one and began working at a Milwaukee airfield. When Chapelle's mother learned of her affair with a pilot, she was sent to live with her grandparents in Florida."

After working in a series of jobs in Florida, she found employment with Trans World Airlines (TWA) in New York City. She attended photography evening classes run by Tony Chapelle. She eventually married Chapelle. This ended in divorce but she adopted the professional name Dickey Chapelle. She took the name "Dickey" from her favorite explorer, Admiral Richard E. Byrd.

During the Second World War she become a war correspondent photojournalist for National Geographic. In 1942 she spent time with the Marines who were on training courses in Panama. This included covering the battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa with the Marines. Roberta Ostroff, the author of Fire in the Wind: The Biography of Dickey Chappelle (1992) has argued that she "was a tiny woman known for her refusal to kowtow to authority and her signature uniform: fatigues, an Australian bush hat, dramatic Harlequin glasses, and pearl earrings."

After the war, Dickey Chapelle covered all the major wars and rebellions. This included the Hungarian Uprising in 1956, where she was captured and jailed for seven weeks. This was followed by spells in Algeria and Lebanon. She later wrote in What's A Woman Doing Here?: A Reporter's Report on Herself (1962): "I had become an interpreter of violence. I'd covered three revolutions in three years - Hungary, Algeria, Lebanon.... I minded the larger truths that the revolutions had failed. Hungary had fallen to the tanks. Brother still fought brother in Algeria. Rioting continued in Lebanon. But men continued to hope and fight for a better world."

In the summer of 1958 she was sent by The Reader's Digest to cover the uprising against Fulgencio Batista in Cuba. She was not impressed with what she saw in Havana. "Around his empire of corruption, Batista built a secret police organization. The letters SIM and the sleek olive drab radio cars with submachine gun barrels poking through their windows appeared in the streets. Every police station in the large cities was said to have its own torture chamber. A fifty-year-old woman schoolteacher who during an interrogation had been violated with a soldering iron in Havana's XII district, February 24, 1958, described the building. She said the chief's office had walls of tile and drains in the floor so it could be cleaned with a hose each day."

Along with two of her fellow reporters, Herbert Matthews and Andrew St. George, she managed to interview Fidel Castro. She later recorded: "The emotional tension around him rarely lessened; he conveyed high pressure in every movement and was never still. His normal state of ease was a purposeful forty-inch stride forward, then back (it was nearly impossible to photograph him). His speaking voice was surprisingly soft and his incessant speech distinct. His manner of giving praise was a bear hug, his encouragement a heavy hand on the shoulder, his criticism an earthquake loss of temper. He reacted with gargantuan anger to every report of dead and wounded; I considered this evidence that lie had never suffered the magnitude of losses Batista claimed.. The overwhelming fault in his character was plain for all to see even then. This was his inability to tolerate the absence of an enemy; he had to stand - or better, rant and shout-against some challenge every waking moment... In the rare times when he spoke quietly, Castro revealed a fine incisive mind utterly ill-matching the psychopathic temperament which subdued it."

After Fidel Castro gained power, Chapelle campaigned against the new government. In March 1963 she joined forces with Henry Luce, Clare Booth Luce, Hal Hendrix, Paul Bethel, William Pawley, Virginia Prewett, Edward Teller, Arleigh Burke, Leo Cherne, Ernest Cuneo, Sidney Hook, Hans Morgenthau and Frank Tannenbaum to form the Citizens Committee to Free Cuba (CCFC).

Miller Davies, reported in the Miami Times, that Felipe Vidal Santiago saved Chappell's life in January 1964, when her boat caught fire off Key Biscayne. The newspaper reported that "Vidal Santiago, close by in his own boat rescued Miss Chapelle and rushed her to Jackson Memorial Hospital." Four months later it was reported that Santiago, a CIA agent, had been executed in Cuba.

Chapelle's anti-communism encouraged her to volunteer to cover the Vietnam War. Her early reports were highly sympathetic to the small numbers of United States military advisors in the country that were attempting to defend the Ngo Dinh Diem administration.

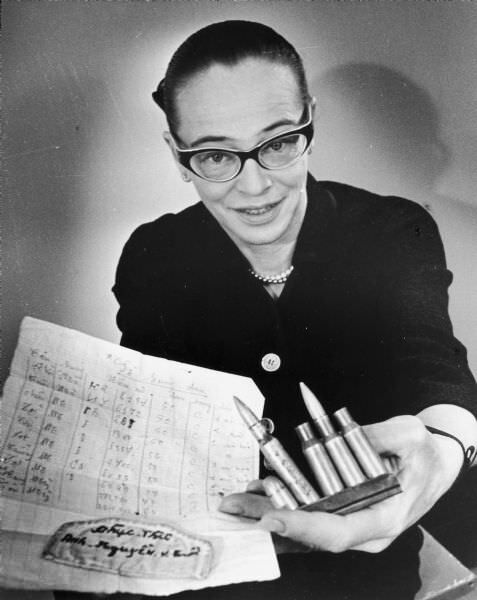

Chapelle with bullets, date of photo not known

Chapelle passionately argued for the sending of combat troops. After the assassination of John F. Kennedy, his deputy, Lyndon B. Johnson became the new president of the United States. He was a strong supporter of the Domino Theory and believed that the prevention of an National Liberation Front victory in South Vietnam was vital to the defence of the United States: "If we quit Vietnam, tomorrow we'll be fighting in Hawaii and next week we'll have to fight in San Francisco."

On 8th March, 1964, 3,500 US marines arrived in South Vietnam. They were the first "official" US combat troops to be sent to the country. This dramatic escalation of the war was presented to the American public as being a short-term measure and did not cause much criticism at the time. A public opinion poll carried out that year indicated that nearly 80% of the American public supported the bombing raids and the sending of combat troops to Vietnam.

Chapelle was one of the few reporters who went with the US Army on search and destroy missions. This included Operation Black Ferret. On 4th November, 1965, the lieutenant in front of her kicked a tripwire boobytrap. Chapelle was hit in the neck by a piece of shrapnel which severed her carotid artery and died soon after. She became the first female war correspondent to be killed in action.

Content originally published on http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/JFKchapelle.htm