Copyright Dickey Chapelle/Wisconsin Historical Society

by Andy, posted on Filmus Monochromus

“Get that broad the hell out of here!” That unchivalrous comment was leveled by a United States Marine Corps general at Dickey Chapelle, a woman photographer who had made her way to his front during the bloody battle of Okinawa, toward the end of World War II.

I admire and respect war/combat photographers, whether service or civilian. It is not easy keeping your head above the parapet and concentrating on getting the image whilst someone is raining crap down on you. Part of your brain is in survival mode and screaming, “get out, get down, take cover.” The other part is saying, “get the shot, concentrate, just one more, you’ll be OK.” I have met a few war photographers during my time in the Royal Navy serving with the Marines and they are a special breed.

But, women war photographers truly are a special breed.

Margaret Bourke-White, Lee Miller, Therese Bonney, Toni Frissell, Jillian Edelstein, Jillian Edelstein, Susan Meiselas, Gerda Taro (Robert Capa’s partner), An-My Lê, Stephanie Sinclair, Andrea Bruce, Deborah Copaken Kogan, Alexandra Boulat, Ami Vitale, Heidi Levine, Kate Brooks, Paula Bronstein, Carol Guzy, Carolyn Cole, Lynsey Addario, Samantha Appleton, Catherine Leroy - I could go on!

But for me Dickey Chapelle is up there with the best. Read on……

Dickey Chapelle, born Georgette Louise Meyer (March 14, 1918–November 4, 1965), was an American photojournalist known for her work as a war correspondent from World War II through the Vietnam War.

Chapelle was born in Shorewood, Wisconsin and attended Shorewood High School. By the age of sixteen, she was attending aeronautical design classes at MIT. She soon returned home, where she worked at a local airfield, hoping to learn to pilot airplanes instead of designing them. However, when her mother learned that she was also having an affair with one of the pilots, Chapelle was forced to live in Florida with her grandparents.

Eventually, she moved to New York, and met her future husband, Tony Chapelle, and began working as a photographer sponsored by Trans World Airlines. She eventually became a professional, and later, after fifteen years of marriage, divorced Tony, and changed her first name to Dickey.

Despite her mediocre photographic credentials, during World War II Chapelle managed to become a war correspondent photojournalist for National Geographic, and with one of her first assignments, was posted with the Marines during the battle of Iwo Jima. She covered the battle of Okinawa as well.

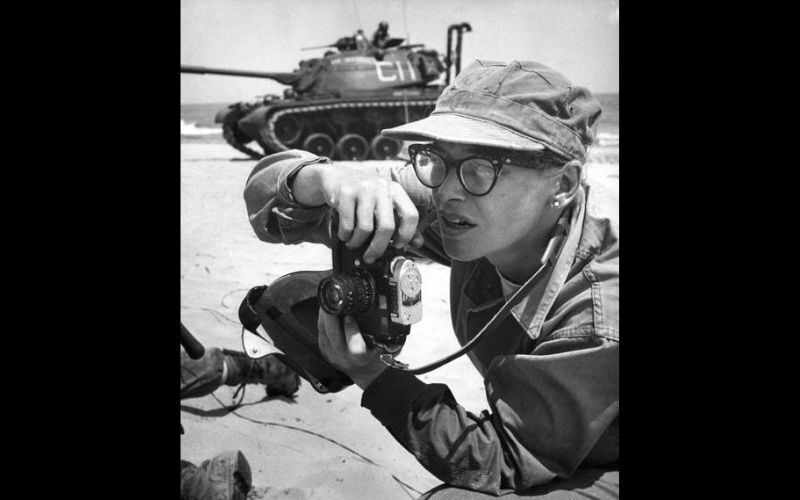

After the war, she traveled all around the world, often going to extraordinary lengths to cover a story in any war zone. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, Chapelle was captured and jailed for over seven weeks. She later learned to jump with paratroopers, and usually travelled with troops. This led to frequent awards, and earned the respect of both the military and journalistic community. Chapelle was a tiny woman known for her refusal to kowtow to authority and her signature uniform: fatigues, an Australian bush hat, dramatic Harlequin glasses, and pearl earrings.

Dickey left the United States for Vietnam in 1961. Out front, as usual. Alone. The first American female journalist in search of the biggest story of her already-memorable career. After a trip to Laos where she observed unacknowledged American CIA operatives in combat there, Dickey came to realize: nobody back home had a clue to what was about to happen in Southeast Asia. And nobody was buying her dispatches.

The American government tried its best to discredit Dickey Chapelle. And let’s face it: the “girl” who’d rather be a combat marine, the “troublemaker” who smoked, drank, jumped out of airplanes, and slept in the mud with men young enough to be her sons was an easy target. Except they couldn’t hit her. Not the way she kept out in front of the crowd. The government adapted a more nefarious approach to controlling their pint-sized time bomb—playing upon Dickey’s unabashed patriotism, they put her to work for the CIA. And 800 of her photographs “disappeared.”

The official, credentialed press corps in Vietnam in the very early 60’s was a bunch of callow kids, for the most part, more interested in scoring good weed and great broads then they were in uncovering a story that officially didn’t exist yet.

It was National Geographic, ironically, that brought the Bad News home. While on assignment for that august magazine in 1962, Dickey photographed a U.S. Marine, in uniform, combat-ready in the door of a helicopter, surrounded by a cadre of South Vietnamese soldiers. It was the first published photograph of an American in combat in Vietnam and it won the 1963 Press Photographer’s Association “Photograph of the Year.”

Her photograph of the execution of a supine “suspected” communist prisoner by a Vietnamese Airborne officer predated Eddie Adams’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photo “Guerrilla Dies” (the famous one of the police chief pulling the trigger of his pistol up against his bound captive’s head) by six full years.

Chapelle was killed in Vietnam on November 4, 1965, when on patrol with a Marine platoon, the lieutenant in front of her kicked a tripwire boobytrap, consisting of a mortar shell with a hand grenade attached to the top of it.

Chapelle was hit in the neck by a piece of shrapnel, her carotid artery had been torn open, and died soon after. In an evac helicopter, somewhere above Chu Lai, Vietnam, the veteran photographer had looked at a crewman and said, “I guess it was bound to happen.”

Those were her last words. Her last moments were captured in a photograph by Henri Huet.

Her body was repatriated with an honor guard consisting of six Marines and she was given full Marine burial. She became the first female war correspondent to be killed in Vietnam, as well as the first American female reporter to be killed in action.

U.S. Marine Corps chaplain John Monamara of Boston administers the last rites to war correspondent Dickey Chapelle. (Note the pearl earring) Copyright Henri Huet/AP

Dickey Chapelle’s grave. Copyright Tmprmtl. She is buried at Forest Home Cemetery, Milwaukee, Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, USA. View Dickey’s photos at the Wisconsin Historical Society.