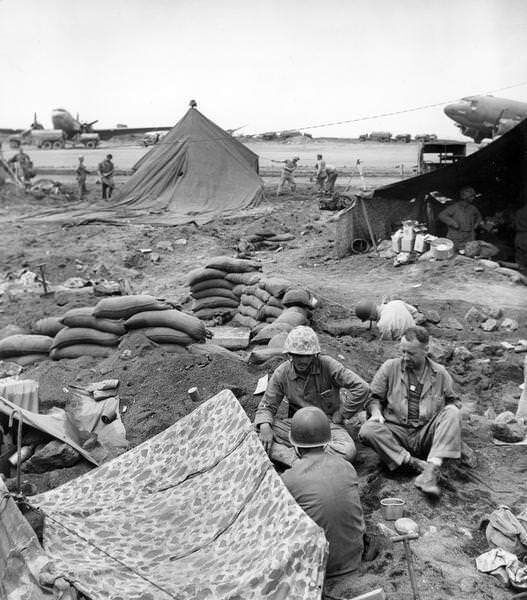

Iwo Jima Airfield

The following writing by Dickey Chapelle is from her book, What's a Woman Doing Here?. The chapter is "On to Iwo Jima." All of the pictures were shot by her. Not all photos were shot on Iwo Jima.

AFTER MY RETURN from Panama in 1943, I worked on two editions of Aviation Annual (Doubleday Doran) and wrote about eight books on aviation.

On Easter of 1944, Tony was told that the government wanted him to begin preparations to set up photographic centers in Asia for propaganda purposes. So he would be out of uniform and working from the Army Pictorial Center on Long Island. In the middle of the war, we'd be able to have an apartment together in New York!

The one we found was on Riverside Drive with a wide view of the Hudson River. Here I tried to be a housewife again plus a writer of two thousand words a day. This routine went on for almost a year and scarred me for life. To turn out those eight pages every day involved discipline, probably the first I'd ever faced. Years later, when I hesitated about walking across the Iron Curtain or jumping out of an airplane in flight, I could still move myself off dead center by saying, sometimes out loud,"Well, it's better than writing two thousand words a day, isn't it?'*

Just before Christmas of 1944, Tony's project suddenly was ordered forward. He was to go to Chungking. He had been administered his inoculations, measured for his Office of War Information uniforms and was standing by to hear the date of his departure.

I didn't know what I was going to do while he was gone this time. But I was pretty sure it wouldn't be writing two thousand words a day while gazing across the Hudson toward China.

Iwo Jima Medical Facilities

I decided to ask for a magazine assignment to the theatre of war adjoining Tony's. This was under the command of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. We were sure it would take a long time to get recognition from Washington, probably ninety days. It had taken me even longer than that to set up the trip to Panama.

Ten days later, Tony faced what must surely be the most awkward moment in a husband's life. His own orders inexplicably delayed, he had to say good-bye to his wife while she went off to war.

The lightning bolt which had catapulted me out couldn't even be called luck. It was just a matter of timing. I'd started by calling at a magazine chain which had printed many of my pictures and stories about women in unusual war jobs, Fawcett Publications. Two of their magazines were Woman's Day and Popular Mechanics. Its managing editor was fiery, short-spoken Ralph Daigh. I had no reason to be really hopeful when I came into his office. I began by saying I wanted to cover what women were doing in the Pacific "and anything else that happens while I'm out there"

He didn't let me finish. "We need somebody out there right now. Go ahead. Just be sure you're first someplace."

Fawcett's application for my recognition by the Government ground through the machinery in Washington in an incredible forty-eight hours. There was a clearing-house for reporters, accreditation now, functioning like a well-oiled machine.

Enroute to the Pacific, I was ordered to join a tour for a dozen other women writers visiting naval air stations in the United States. It was to leave by plane from Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn at the end of the week in which my request had been filed.

This accreditation business is of the greatest importance in wartime to a reporter or a photographer (or a reporter- photographer as I was). It's not enlistment. The correspondent goes right on being paid by his publication. But the service Army, Navy, Air Force agrees to see that the correspondent is housed, fed, uniformed, transported and shown whatever is necessary. The services give this cooperation so the correspondent will at least be able to write stories useful to the prosecution of the war as well as satisfactory to his editors.

In return for adopting him or her, the military forces ask one commitment from the correspondent. The reporter agrees in writing to take orders. The custom is to treat a correspondent as a kind of junior officer, calling the status he doesn't legally have a simulated rank. In 1945, we were simulated captains in the Army and lieutenant commanders in the Navy.

My orders said I would "report aboard" at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue for transportation to the Pacific Fleet at 0800 on 20 January. This was eight o'clock in the morning. Ready for boarding at the designated spot I found a highly polished blue station wagon with an impatient young sailor-driver.

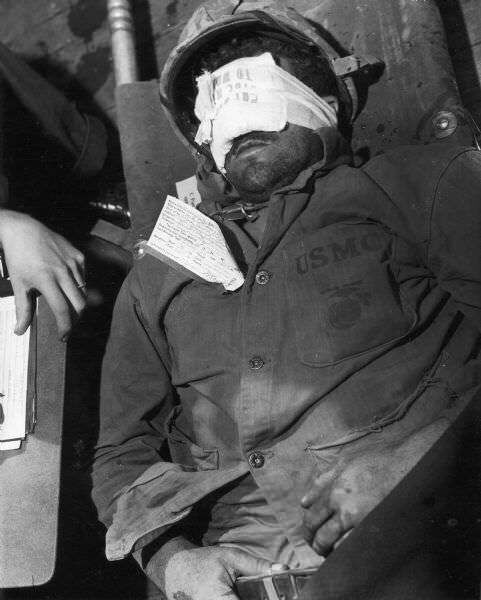

Wounded Marine on Iwo Jima

Standing in the icy street under billowing snow clouds, Tony and I said our farewells. I felt guilty as the dickens, leaving him.

"Now, let me see, Mrs. Chapelle," the lieutenant began, riffling the papers in his IN basket, "are you a writer or a photographer?" We were sitting in his office on the Naval Air Station at Oakland, California, on an icy Februray morning and I probably had my head cocked a little to one side as I studied him. He was the first government correspondents' aide I'd ever met, a lieutenant junior grade whose job was liaison from the Navy to the press.

I told him I'd be working as both reporter and photographer, since my magazines had no one else in the area.

"You can't be both," he told me firmly. "On operations, you may use radio facilities if you are a writer, or your camera if you are a photographer. But only one." I didn't understand what he meant by "on operations." I was pretty sure the term in wartime usually meant "in combat." But certainly the Navy would never consent to a woman observer where there was any shooting! I wasn't willing, though, to ask the lieutenant any silly questions as long as he was taking my professional role so seriously. So I just

looked thoughtful and asked, "How many accredited women writers has the Navy sent out from San Francisco?"

"A couple, I guess."

"And how many accredited woman photographers?"

"Never heard of one."

That settled it. Now anything I did, including breathing, west of where I sat was a scoop of some kind. "I'm a photographer, then."

"Very well. And just where was it you wanted to go?"

Now I really was surprised. I thought he'd tell me where I was permitted to go. Did he honestly mean I had a choice? Very well, I'd make one. I'd tell the truth.

"As far forward as you'll let me."

Once I'd said it, I was delighted with the way the sentence rang and echoed, like a bell. I expected it would get me to Honolulu, anyway. I knew this was the most advanced station for WACS and WAVES.

The next day, my guess proved right. With a score of Navy flight nurses just out of training, I took off at six o'clock in the morning aboard the largest plane built up to that time, the Martin Mars. She was going to Pearl Harbor.

While we were still in the air, I heard the words Iwo Jima for the first time. The co-pilot climbed back from the cockpit Into the compartment where we sat amid the plane's load of freight and told us the Marines had landed on the little island. He had to shout but he spelled Iwo Jima for us. Then he said the landing was not going well "It's worse than Tarawa.”

In a few minutes, the rainbow shoals of Oahu, overlaid with the pearl light of dawn, were sliding beneath us. An hour later, I stood before a racketing teletype in the press room at Navy headquarters. The co-pilot had been correct. It was worse than Tarawa.

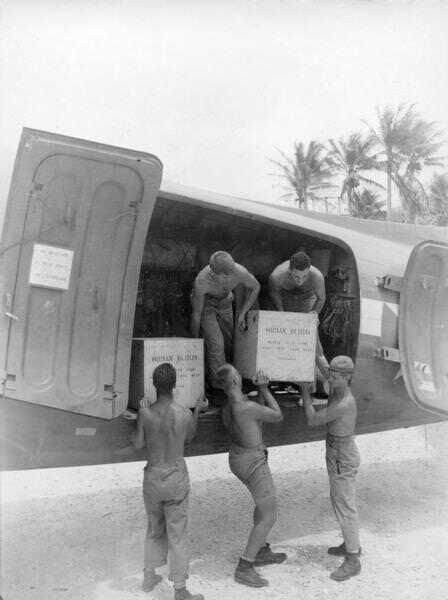

Transferring a Wounded Soldier onto the Ship

Every reporter, editor, public relations officer and correspondents' aide in the building sat before the teletype hour after hour. If we were riveted there at first by something professional, by four o'clock the next morning it had become something morbid. The reports never stopped coming and there was not one that did not tell of fresh disaster. Whole outfits were being committed, macerated, decimated, destroyed.

Somebody said hoarsely that the Corps couldn't take that kind of losses. I nudged an ensign next to me and asked, "What Corps?"

"Marine Corps. Maybe there won't be any more Corps after this."

Like all tyro correspondents in the face of their first bad news, I thought at once of the blackest catastrophe. Could could the United States be losing the war?

I was certain of one conclusion. No matter what stories Fd come out to cover, no matter what any editor in New York had thought I ought to do, I didn't have to be concerned about it now. There was in all the world at this moment only one story. Just one. Men killing and dying, real men, now, in this instant, on Iwo Jima.

So when a correspondents' aide asked me where I wanted to go, I made the only reply I could imagine a correspondent making. "As far forward as you'll let me."

I shortly received orders which I was told were similar to those of the nurses with whom I'd been traveling. They directed us to Guam. This marked the first break-through of American women in the armed forces to a post of duty forward of Honolulu, and I thought wistfully that our going on to Guam would have been news if there had not been just one story in the whole area.

At Guam the news from Iwo Jima was no different.

Doctors with Wounded Man

But here, the teleprinter in the correspondents' workroom was a magnet for only a handful of men. They were the rewrite experts of the press associations who had stayed behind to relay the dispatches from their colleagues at the front, now only a few hundred miles away. The teletype was linked directly to the communications ship of the assault fleet, the U.S.S. Eldorado.

OFFSHORE AT IWO JIMA (DELAYED ONE HOUR IN TRANSIT) THE MORNING OF D DAY PLUS THREE HAS COME HERE FOR THE MEN ALIVE TO SEE IT. BUT INCOMPLETE CASUALTY REPORTS INDICATE THAT FOR ONE OUT OF TEN AMERICANS WHO CHARGED ASHORE HERE THERE HAS BEEN NO SUNRISE. THEY DID NOT SURVIVE . . .

A slight man wearing steel-rimmed spectacles grumbled, "Poetic, isn't he, this morning? But those figures never will pass the censor, and by God I don't think they ought to.”

WITH THE ASSAULT FORCE AT IWO JIMA IT IS UNDERSTOOD THAT UNITS OF THE THIRD FOURTH AND FIFTH MARINE DIVISIONS HAVE BEEN COMMITTED. IT WAS SAID THIS MORNING THAT MAJOR GENERAL GRAVES B. ERSKINE COMMANDER OF THE THIRD DIVISION DID NOT PLAN TO ORDER FURTHER RESERVES ONTO THE BITTERLY CONTESTED

LITTLE . . .

"God! He's sentenced every man already there to death!" someone said. I'd thought press association re-write men were supposed to be hard-boiled. But the face of this one was white and stiff.

ABOARD THE COMMAND SHIP OF THE ASSAULT FORCE ANCHORED OFF IWO JIMA AN UNCONFIRMED RUMOR IS SWEEPING THE SHIP THAT THE FLAG HAS BEEN SIGHTED ON THE TOP OF THE HIGHEST POINT OF THE SAVAGELY CONTESTED SOIL OF ...

Flight Nurse with Wounded

Now the men were scornful. They said the teleprinter operator aboard the Eldorado must be making a bad joke. They agreed not to relay such an improbable rumor back to their offices in the States.

The teletype began to click again.

IT HAS BEEN OFFICIALLY CONFIRMED THAT THE FLAG OF THE UNITED STATES NOW FLIES FROM MOUNT SURIBACHI HIGHEST POINT OF THIS VOLCANIC ISLAND. . . .

The words galvanized the press room. Three of the men cheered. Now that I was sure it was all right for a correspondent to show emotion, I wiped my eyes with my knuckles. The Associated Press man was not quite so obvious about it. He just wiped his eyeglasses and turned back to his typewriter.

Then the correspondents' aide with whom I had been ordered to work motioned me into his office. He was a lanky redheaded lieutenant with harassed eyes, named Joe Magee, He told me my living quarters were to be in a tent on a hilltop a few miles away. Then, like all the aides before him, he asked me where I wanted to go.

I still couldn't imagine a correspondent making any other reply but "Iwo Jima." Nor could I imagine that the Navy would let me go. Forlornly I said, "As far forward as you'll let me."

Injured Marine after Treatment

Lieutenant Magee got up, said, "Stay here, girl/' and left the room. When he came back, he was saying, "You now have orders to the Samaritan, that's one of our hospital ships on its way to Iwo Jima. You'll meet your jeep at five o'clock tomorrow morning on the road below your tent. The jeep will deliver you to the ship and she'll be sailing at once. Dickey! Are you listening?"

The real measure of my astonishment was that I found myself in the hilltop tent after sundown without having made any arrangements to be waked up. I knew if I went to sleep then I was good for forty-eight hours without opening my eyes. I'd miss my jeep; I'd never hear even a horn sounded down on the road. Would the driver come up? No. Orders were that no male should come nearer the tent than the Marine guard who patrolled around the base of the hill. Maybe I could get his attention and borrow an alarm clock? I stared out of the tent to see if I could spot him through the trees. No. Well, I'd walk down to the guard post. And then I remembered. Lieutenant Magee had said the Marine's orders were to shoot anything that moved here after dark and ask questions later, if at all. Lieutenant Magee had added that he wouldn't miss.

Well, there was exactly one way out. For nine hours in the dark and silence, I kept myself awake.

The C7.S.S. Samaritan, long as a city block and towering over her pontoon dock, was painted gleaming white with red crosses four decks high on either side. She was one of the half-dozen hospital ships of the Pacific Fleet in action at the time. As she steamed to Iwo to bring back casualties from the fighting, I underwent my baptism of fire aboard her.

In the early afternoon of the second day out, an abandon ship drill was held on the Samaritan. Sonny, a very young slight corpsman, his cherub face almost lost inside the frame of his gray steel helmet, who had become my mentor told me the drill was by the book and made sense at the time since we were empty. But as a battle drill, it was farce; doctors, nurses and corpsmen have never been known to leave their patients for any purpose so trivial as to safeguard their own lives. And no ship loaded with wounded can ever be evacuated.

Even so, I was glad we'd had the drill. I found my action station because of it. Sonny asked me where 1 was going if we were called to security stations.

I said, "What's a security station?"

Wounded Marine

"On a ship that can fight, it's called a battle station. But we don't have a gun or anything, so if we get involved in fighting, it's just for our own safety. Where'll you go?"

"How could we ever get in any fighting?" I asked scornfully. "Isn't this ship protected by the Geneva Convention?"

Sonny was sage. "It don't seem as though the captain trusts the Geneva Convention much. I wouldn't if I was him. You know any Japanese ever heard of it?"

I didn't know any Japanese at all but I'd been raised on the inviolability of the Geneva Convention, the Kellogg peace pacts and the progressive disarmament treaties. Like my mother, I was pretty sure there'd be peace on earth if people just wouldn't get so suspicious of each other. The unarmed Samaritan was afloat out here, wasn't she? That proved the Convention was more than just a piece of paper, didn't it?

Injured Soldier

"Well, if anything happens, where do you want to be?" Sonny was asking.

I abandoned the political issue uneasily. "I guess the camera should be at the highest point so I can see in every direction."

Sonny led me up three ladders. Then we were on a piece of deck a dozen yards across right over the bridge. Beside me was a huge searchlight mounted on metal legs eight or nine inches high.

"Good thing there's room under that searchlight," Sonny said. "You'll have real good cover up here."

"I couldn't get under there if the air was full of bullets," I said.

"Sure you can. You're not that fat," insisted Sonny gravely. "I bet you a quarter."

Before I could demonstrate my point, I was summoned belowdecks, so Sonny and my bet remained unsettled until later.

That night, quartered in one of the vacant private rooms of the sick officers' ward, I practiced for the first time a going- to-bed routine that I was to follow for the rest of my life in any war zone. I reloaded the camera and padded it between extra pillows on the floor so it would have some protection against detonation. I hung my helmet and life belt where I could reach them and then rehearsed with my eyes closed how to find them by feel. I lay down, loosened the web belt of my khaki slacks, made sure my shirt wouldn't choke me and buried my face in my arm. As I fell asleep I was tempted to laugh at myself for all these precautions. The Samaritan had no guns. Why was I acting as if I expected her to be attacked?

The next thing I remember, sound was vibrating the bulkheads and daylight pouring through the porthole. The noise was the alarm klaxon, and it lifted me clear up and into my shoes before I understood what I was listening to. Then I didn't believe it. The squawk box cut in:

All hands man your security stations . . . all hands man your security stations . . .

Throwing on my life belt and not forgetting the helmet, I hurried into the compartment on which my room opened, the sick officers* wardroom. Half a dozen corpsmen were lying flat on their stomachs on mattresses on the floor. I recognized Sonny.

"What's going on?" I asked breathlessly.

"We're being bombed." The loudspeaker broke in:

Blood Transfer

A Japanese bomber type aircraft has just begun a run on this ship. I say again a Betty has just begun a run on this ship. We are the target. All hands take cover . . . all hands t-a-a-ke co-o-o-ver.

I was absolutely certain somebody had simply hooked up the soundtrack of an old movie. I walked toward the wide hatch that opened from the wardroom onto the main deck. At the high doorsill, the sense of the words hit me. I froze. Over and over my mind kept repeating, I-do-not-want-to-go--out-there. I-do-not-want-to....Behind me, a seaman's voice rang young and clear in the stillness.

"Photographers are crazy."

That was what it took. As long as one person thought I was a photographer, I was willing to take the next step toward being one. But out on deck, it got hardernot easier.

The sun was bright, the sea was bare and blue, the decks of the ship were utterly, desolately, lacking any sign of another human being.

I could see the enemy plane clearly from where I stood. It was too far away to show in a photograph, but a black speck now detached itself from underneath the plane and began falling toward us, growing bigger and bigger as it came.

I heard a sigh of voices from every deck level. Not until the bomb had splashed into the water a few hundred yards behind us did I realize that it had been a sigh of relief. Everyone else who could see from their security station had known that the pilot had released too soon, and the bomb would miss. I hadn't. And I surely hadn't gotten any picture.

The bomber was circling and rising now, and I ran for the nearest ladder. I saw the whole war in that instant in clear terms. It was a race between him and me. I had to get up to the flying bridge before he had positioned his plane for the next run.

I made it. And threw myself flat on my stomach on the corrugated metal, bracing the camera with my elbows. I had about lined up the plane in the finder when it occurred to me what I was doing. The wire frame of the finder before my eyes began to tremble, then to wobble.

"All hands ta-a-a-ke co-o-o-ver . . . All hands ta-a-ke co-o-ver . . . "

Suddenly every part of me except my helmet, hands and camera was under the searchlight platform. It was crushing me, mangling me. But I was covered.

From there, I tried to steady the camera again. In the finder the plane grew big. The enemy pilot was beginning a second run on us, and all he had to do this time was wait a few more seconds before he toggled loose the bomb. Would it explode near the bow or stern (where I wasn't) or 'mid- ships (where I was)? Time spun out . . .

No bomb came. Instead I saw an orange lance in the sky and then a ceaseless stream of them arc toward the plane. A Navy destroyer was opening up with all her anti-aircraft guns as she charged across the water toward us. The bomber lurched off-course, veered and banked so the Rising Sun on her wings was plain. She jinked again to escape the ack-ack, climbed up and, without loosing another bomb, turned tail and fled.

By the pure chance that a destroyer heading out from Iwo had passed us at the critical instant, we were safe.

I remember one seaman's idea of celebrating our deliverance. All day he slid quietly in behind people and let his steel helmet crash on the metal deck. If this produced a broad jump under ten feet, he said your reflexes were under par. Mine were okay.

Return to Guam

There was a note of shame to my celebrating, anyhow. I had no telephoto lens, and what there'd been to photograph had happened a long way off for a normal lens. I knew what Tony would say to an alibi like that. The fact was that I hadn't shot even the flyspeck-in-the-sky kind of picture I should have made. In short, I'd fluffed the coverage of my own baptism of fire. But there was one point of personal honor to be salvaged.

I looked up Sonny and held out a twenty-five cent piece.

"You win,"I said. "I'm not that fat."