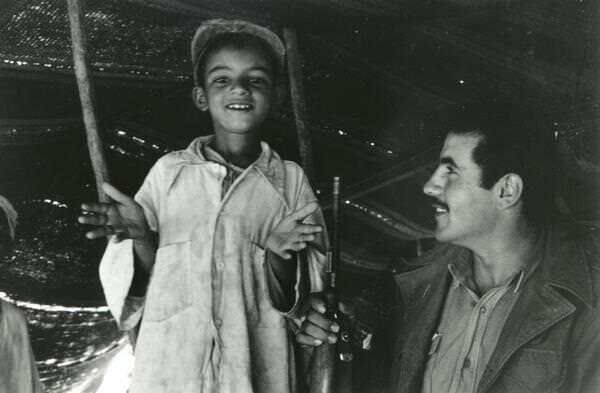

Agerian Bedouin Boy

The following writing by Dickey Chapelle is from her book, What's a Woman Doing Here?. The chapter is "Operation Squirrel: Algeria" All of the pictures were shot by Dickey Chapelle.

NOT FAR FROM the United Nations, in a chastely modern apartment building, are the U.S. Headquarters for the Algerian Federation of National Liberation.

On a still hot day in July, 1957, I had my first interview there with Abdel Kadar Chanderli, FLN Chief in America and representative for the UN of the Algerian rebels. Cool and knowledgeable, Abdel Kadar was talking to me bluntly about the convulsions of violence between the French and the Algerians, which he felt were not being reported in the American press for what they were, a war. He reminded me that Algeria was three times larger than Texas, that it was bounded on the east and west by great long barriers of French barbed wire and on the south by the Sahara Desert. He said the normal flow of information was blocked at every border, and that it was easy for the French to arrest anyone delivering reports of FLN tactical movements to the press associations in the big cities. Airlines and telephones in Algeria were in French hands, he said, and those in adjoining Morocco could be monitored by the French, too, since their troops had not left the country in spite of its nominal independence.

I insisted that, while I thought communiques from any side of any war were untrustworthy, there must be a way to get word from the rebels to the American press.

Abdel Kadar nodded. He said there was; he had arranged to send an American journalist directly from New York to cover the fighting from the rebel side. He went on, "It's never been done before." Then, looking deeply hurt, "Now I can't find anybody who will go."

I asked how long such a trip would take. He said he didn't know. The reporter would have to be smuggled in, travel on foot or muleback to the forward areas, and come out undercover again.

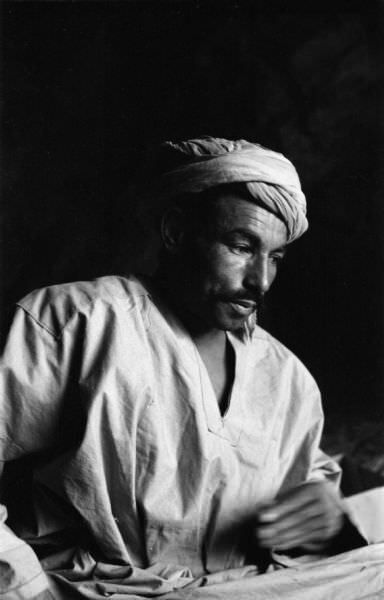

Algerian FLN Portrait

"What kind of a story would the reporter get?"

Abdel Kadar looked only pained now. "I don't know. It depends on the tactical situation while the person is with us."

"What's the first step?"

"Kidnapping this American correspondent out of Madrid,” he replied.

I thought hard for a long time, although I knew the proposal would not improve by being too carefully considered. "Right now you need a guinea pig with no dependents, no commitments, little backing and a positive taste for being a kidnapee."

"You state our position well," came the dry answer.

I began, "I know a member of the U.S. press who meets the description. But" I paused. A woman on a war assignment in the Arab world?

Abdel Kadar was leaning back and smiling broadly. "Did you really think I meant to turn you down?" He went on to tell me he had made sure I was acceptable to his people before he spoke with me. He had told them I did not mention the name of any of the Hungarian freedom fighters when I was interrogated by the AVO.

I burst out, "But I couldn't have! I made a great point of never knowing anyone's name!"

Abdel Kadar shook his head and said he didn't believe me. But on that frail proof of my ability as a conspirator, the Algerian rested the lives or, at least, the identification of more than a hundred of his countrymen and the staffs of three battalions.

Once I made up my mind to go on the mission, there were only a few more things to be done. I first signed a contract with Spadea Syndicate, a small press association run by a father and son, Jim and Sterling Spadea, who accepted my insistence on secrecy and nonetheless gambled the roundtrip air fare to Madrid that I'd bring back articles the fifty-five daily newspapers they serviced would want to print.

Then I packed my cameras and called on Abdel Kadar again. I told him I wanted a new name. Somehow I didn't think Chapelle had quite the happiest implications for a person covering fighting among avowed enemies of France.

"You already have one/' the Arab replied. "We call the project of moving you and ensuring your safety with our army OPERATION SQUIRREL." He paused and broke into a smile. "I decided 'guinea pig' had no poetry. So go now, and courage, Squirrel."

It was not a great hill, surely not a mountain, the peak the Algerian soldiers called Black Point. Just a stark knife-edge rise above a bare ridge stretching almost to the far horizon. The point itself was not as high as the Empire State Building.

But it marked a real boundary. To the south lay the Algerian Sahara, a vast wasteland unpeopled now in the white heat of late July. Dimly to the North there rose the Atlas range, mountains that girdled half North Africa. Between lay many miles of foothills, the area of responsibility of the Algerian battalion four hundred uniformed infantrymen to whom I had been sent.

It was in part to control such areas that French troops had been released from NATO lines in Europe. But in this moment, shimmering orange and green and purple under a setting sun, the rocky hills lay utterly lonely. Our light footsteps were the only claim on them.

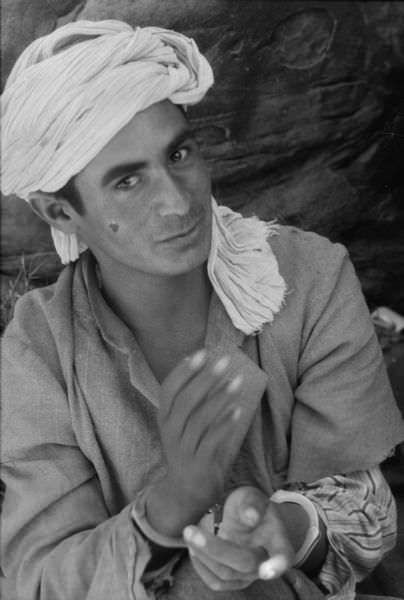

Algerian Soldiers

I had reached the area by being passed like a package through a working underground that, as Abdel Kadar had told me, spanned borders halfway around the world. I had been moved by plane, car, truck, horse, mule and on foot. My escorts, changing almost every day, had been Algerian sympathizers in Europe, and Algerian refugees, couriers and infantrymen in North Africa. I had traveled, blindfolded, in a borrowed dress as a German tourist, and as a veiled and berobed Arab woman. I had been quartered in Arab homes and stables and ammunition dumps in half a dozen Moroccan towns, in the tribal tents of Berber herdsmen and finally in the rock caves of the Ksour foothills three days' walking from the border between Morocco and Algeria.

One of the caves, supplied with two blankets and a bed of alfalfa, had been my home for ten days. Other nearby caves on a cliff comprised the battalion command post, the base from which the rebels almost every night sortied out to halt any vehicle by mining the roads or by ambush. The battalion, like the Arab tribesmen, did not miss the roads, for they had no vehicles of their own. The roadside wrecks I'd seen were of French army trucks and armored cars. The rebel unit called itself the Scorpion Battalion (after its home among sun-warmed rocks) and had just been decorated by the FLN for blowing up the French rail line from nearby Colomb Bechar to Oran regularly three times a week.

Among the Scorpions I'd seen one evidence of the battalion's importance in the eyes of the French. The area was under daily, sometimes hourly air attack by light bombers that bore the French tricolor.

On the patrol I was accompanying up the hill called Black Point, we had no fighting mission. We were only scouting, and would be back in two or three days, as soon anyway as we had eaten all the dates and sugar and bread and tea in the men's packs.

We were only a dozen people, and it seemed easy to keep up among them at first, as if I could push the hill down behind me with each step up the tumbled, stair-like rocks.

Behind me climbed Captain Ben Chafa, the battalion commander. He was short, slight, white-skinned. His lithe person exuded all the mystique of a good infantry commander. He had been trained by the French. He was Algerian-born; his father had been a colonel in the French army, Ben Chafa told me, earning a third the pay of his European colleagues for performing the same duties. As a boy, Ben Chafa was a pupil in the school run by the French for the children of their officers. Here he had learned French, and he and I used a pidgin-version to speak with each other. But because Ben Chafa's father was an Arab, the boy had been required to keep his head shaven while French youngsters wore their hair naturally. He had earned the scar across the top of his head by rebelling against the order. When he let his hair grow, one of his schoolmasters stripped off a piece of his scalp.

If this explained today why the young Arab captain was fighting against Europeans, it had left no acid cast to his cool gray-eyed gaze. He had the professionalism, the sang froid of a company commander in our Marines. Making war had been his family's tradition; war was his own. And in his neatly-kept uniform an army shirt, bloused green twill trousers and a pair of brown tennis shoes he didn't need the black necktie or striped epaulets to mark him as the man whose orders we were all taking.

It was he who had told me that the French had bombed and dropped flaming gasoline on Black Point the previous week, apparently gambling that it sheltered the Scorpions' headquarters. They were wrong, but straddling Black Point was something almost as important to the rebels the track along which mule and camel caravans brought in ammunition and gunpowder.

Executed Man

Ben Chafa had said it must be kept clear or his people could not go on making the charges to interdict the rail line. He finished, "Please come with the patrol so your people later can see a photograph of an unexploded bomb. It will show from the markings on the fins that it is one of the aerial bombs supplied to France from your country."

I watched the feet of the climber ahead of me and put my own feet where his dusty sandals had been. Their soles were cut from U.S. war surplus truck tires, and he was leaving parts of the words GOODYEAR and FIRESTONE in the gray sand.

He was a junior lieutenant named Lamara, very young and tall and thin. His pale face wore an expression of surprise as if he could not imagine how he had become involved in a warlike effort. He spoke Arabic, French and English, and was my interpreter. Until he enlisted, he had been a student in a university in France. He still hoped to teach school some day in an Algerian village free Algeria, of course. His hobby was history and he carried a book in his pack. He had shown me the text of a treaty in it which President Madison had negotiated with Algeria in 1812. He remained unabashed when I pointed out that the purpose of the treaty was to stop piracy off the coast of Tripoli. He said that wasn't the point; what he wanted me to understand was that the United States had recognized his land as a nation in its own right one hundred and fifty years earlier.

I tried now to let Lieutenant Larnara's easy movements hypnotize me into moving faster. But he heard my footsteps falter. He turned and said over his shoulder, "One must hurry. The moon will be early and clear tonight. Anyone in the valley, perhaps a French patrol, will be able to see us here, so we must cross the ridge without delaying."

He extended his hand behind his back to me. I put my hand in his and at once he began to climb again, accepting at each step whatever part of my weight my own legs disclaimed.

In this way, we reached the top of the ridge.

The next day we located the unexploded bombs the mule driver had reported. I photographed one; it was indeed a NATO weapon, a hundred-pound high explosive aerial bomb. The officers agreed the bombs were far enough off the mule track so they did not need to be detonated.

Rebels in the Atlas Mountains

That night, we picked our way down to the hillside again, slowly for the moon would rise later.

As the days passed, I knew I was learning several new abilities I'd never be taught by American military forces. How to live in the desert in August with only a pint of water and two cups of tea a day. How to limit my urination to once a day so I would not need any more liquid, and to robe myself with a thick blanket when I went out into the noonday sun so I would not lose water by perspiring. How to work on only half a dozen dates and a chunk of sugar half the size of my hand every day. How to walk for five hours without a break and to sleep well on rock. Laugh at myself though I should, the pride I felt was important and bigger than the hurt in my throat from the thirst or the ache in my back from the rocks.

One morning Lieutenant Lamara told me I was to accompany the next trip of the battalion staff forward of headquarters. But it would be too far for me to walk; he asked if I was a skilled horsewoman. I said I was not. A patent lie, since I was not a horsewoman of any kind, my only previous experience being some fifteen minutes in the saddle in Panama in 1942. With that quick perception of incapability that distinguishes experienced soldiers, the officers understood. They found a mount for me which obviously had never heard any propaganda about Arab horses being spirited. He was dappled, handsome and double-gaited: slow walk and full stop were the gaits. Moreover, a young soldier always led him when I sat in the saddle. The men had christened the horse after the political backing and filling of the French governor-general of Algeria, and the animal answered to the name La Coste.

The mission of the trip I made on La Coste was not military. I photographed five tribes of shepherds some five hundred people in all become part of the FLN. I watched and took pictures while the turbanned Berbers gave their oath of fealty, their sheep, their tax money and some of their sons as enlistees to the Scorpion battalion.

Red Crescent Worker Bandaging Wounded Soldier

Then our junior officers held a court for civil litigation, hearing cases involving wills and marriages and contracts. Sitting inside a goat-hair tent before a flag of rebel Algeria, Lamara and two of his colleagues decided the issues and the tribesmen bowed as they accepted their judgments. Proudly, they later told me they had boycotted the French systems of justice so successfully in the area that many European jurists had been driven back to France, their courtrooms closed for lack of litigants. Now each tribe had its own system for law and order based on squads of policemen named and trained by the FLN. What degree of justice would come of the new system nobody debated.

After the final meal with the tribes a ceremonial one, of course, with a whole roast sheep on a tray, giving us all a chance to eat our fill the men invited their sons into the tent to join the official party. One tribal elder had taught his seven-year-old child to stand at attention and salute Captain Ben Chafa. The officer asked him, "What do you want to be when you grow up?"

"I want to come with you. But now," the little boy said, his heavy-lashed eyes immense.

"Leave your mother when you are so little?" asked Ben Chafa with mock surprise.

"I want to fight for my country."

"Fight who?"

"Fight the French."

"When will you stop?"

"When there is not one Frenchman alive on the soil of my country."

"Will you kill your father if he helps the French?"

"With joy," piped the little voice. His father beamed.

And I thought of the little boy's counterpart in Paris, learning from a geography book that Algeria is part of France.

Red Crescent Worker with Patient

It had been a good time, that clear August morning in the command post of the Algerian rebel battalion. The rising sun blessed the mountains around us, reflecting pink and benign across the face of the hill. At the lip of a wide ledge, four of us sat cross-legged on the warm stone floor.

Lieutenant Lamara, his back against the cave wall, stayed a little to one side. Between Captain Ben Chafa and me, a newcomer had settled himself, tall and dark with narrow deep-sunk eyes in a swarthy face. His lips made a straight slash across his heavy jaw. This was the highest-ranking Algerian officer I was to be permitted to know. (It was said in 1957 that thirty-four responsible FLN leaders had been appointed. Eighteen had been identified by the French, captured and imprisoned or shot; ten were in exile, among them Ferhat Abbas who a year later was to become president of the provisional Algerian government. But the remaining six, all military commanders, were still in Algeria.)

The man on the cave lip was a colonel who used the pseudonym Hamitou. He was the rebels' best known designer of high explosive devices: mines, bombs, grenades. Some people said the French would rather capture him than any other Algerian in uniform.

He knew the French language but would not use it, so Lamara was interpreting from the colonel's guttural Arabic. Hamitou had agreed to tell a little about his personal story. It was a grim accounting; as the colonel talked the sunlight lost its beneficence and the shadows felt cold.

Hamitou spoke of himself as the blackest villain. He made clear this was not by birth or reflex or training but by deliberate choice. In no other way did he believe he could so well serve what he saw as his reason for being: to destroy French soldiers.

He wanted me to know how he had joined the rebel forces. During his final year of study in France to become a veterinarian, he had come back to Algeria on his summer vacation. He rode out to visit his relatives who lived in a little desert hamlet. He arrived there within minutes after the village had been raided. No children ran out to greet him; no one was left alive. He ducked under the smouldering roof beams of what had been his uncle's house. After a time, he pulled free the bayonet by which his eleven-year-old niece's body was pinned to the earth floor.

"It was a bayonet of three edges. The forces of only one nation on earth were equipped at that time with such a bayonet those of your country's ally, France/' he finished.

As Lamara translated, looking a little pale, I had been studying Colonel Hamitou's face. Rarely impassive,, it had become distorted almost past recognition. There is only one act to fit what is in his s ace, "l- thought. The act of putting- to-death. Then I remembered. Homicide was his business.

Traitor Awaiting Trial

When the colonel abruptly announced he was done with being interviewed, I arose and carried my burden of unease down the hill. I came to the battalion kitchen, a level space among the rocks where the lamb-and-bean stew for our noon-day meal was bubbling in a huge black pot over a fire of dried reeds. A white-mustached sergeant and two riflemen were tending it, the men helping knead bread dough on a nearby flat rock. I began to photograph them and, over the top of the finder of my camera, I caught sight of another person, slight, not military.

He wore a loose turban and torn Arab robes held together by a big safety pin at his chest. His olive-skinned face peered down at me from a slit in the rock walls. It occurred to me that he was in a strange place; because of the formation of the stones around him, he could not move in or out of it without tortuous climbing.

The cook followed my eyes. "Prisoner," he said. Then I saw the man's handcuffs, silvery in the shaded light. I asked one of the riflemen to summon Lamara.

When he came, I told him I wanted to interview the prisoner. I thought Lamara might demur, but he only said, "Of course, and he offered his arm to the prisoner to help him clirnb out of the cell of rocks in spite of his handcuffs.

Unbidden, one of the riflemen set down the dough he had been flattening and picked up a submachine gun leaning against a rock. He moved swiftly to a post across the only exit from the kitchen.

The gesture bothered me. It made so plain the captured man's helplessness. I thought, Til make my interview as long as I can. I remembered how welcome any diversion was to a person in custody.

Then for the first time I looked squarely at the prisoner.

He was not a man after all he was a boy. Smooth-faced with long-lashed black eyes. How did anyone this young become involved in a shooting war?

He returned my gaze gravely, almost serenely.

I began to ask questions, Lamara fluently translated, the prisoner answered without hesitation. 1 could not sense any reservations in the way he talked, and he used his manacled hands to gesture gracefully.

I listened to the boy for perhaps half an hour. I thought, I don't believe one word of this. Not one word.

The young Algerian before us, with the face and grace of a Victorian poet, told with the greatest detail how he had cut the throats of more women and children than he could count.

Finally he was done and I said to Lieutenant Lamara, "What will happen to him?"

"The death penalty, I think."

Lamara and I picked our way up the hill back to the headquarters cave.

In the cave, Captain Ben Chafa and Colonel Hamitou were seated on the rock floor, sipping tea from the chipped white mugs. A soldier quickly brought two more mugs for the lieutenant and me. The captain, like a courtly host, asked where I'd been.

"In the kitchen," I paused. Should I mention the prisoner?

Ben Chafa smilingly prompted, "Did you interview our prisoner?"

I said, "Yes" and paused again.

Hamitou had not seemed to notice our conversation. His long fingers were doing something with a length of wire, a pair of small pliers and a flashlight battery. Now his deep-sunk eyes flashed up. "And what do you think of our prisoner?"

"I just don't understand him," I burst out. "He is simply talking himself to death.”

Hamitou's contempt had been for the prisoner. Now it was for the reporter, too. The disdain in his face grew deeper. Its impact was direct and personal. He said, "I don't suppose you'd want to cover his execution."

The Trial

Well, there it is, I thought the whole schism between worlds. Not just the two sides of this war. Not just the have nots against the have, nor just chaos against civilization. But the whole blazing rejection by the world of violence for the world of order.

Angrily, I remembered which side I was on. I did not try to keep the emotion out of my voice as I said, spacing the words clearly, "Not unless I cover the trial."

The colonel put his cigarette between his lips and picked up the pliers, squinting at the wire loop through the curl of smoke.

In the stillness I could hear my own words. Maybe they had sounded good enough, but I knew better. I did not want to cover an execution at all. A proper military trial would take time to arrange, though, and with luck I might be elsewhere before it occurred. It occurred.

The cook-sergeant was climbing up the bluff toward us, carrying a great white enamel basin of the thick lamb stew, the one big meal of the day.

Hamitou, Ben Chafa, Lamara and I ate sitting in a circle on the rock floor around the basin. Each of them tore off little bits of the clear lean meat with the edge of his spoon and pushed it toward my spoon. The colonel did it imperiously, the captain mechanically, the lieutenant with difficulty. I wondered if they had read the old fairy tale which defined love as a very old couple eating out of one bowl, each pushing toward the other the choicest bits of food. It was a French story, and they had all lived in France.

The men were talking in Arabic among themselves without much inflection; shop talk, obviously. Once Ben Chafa called for a noncom who saluted and stood at attention just outside our circle. The officer seemed to be making a suggestion. The soldier demurred stiffly. The captain said the same thing again, inflecting it as an order. The soldier saluted, about-faced and went down the hill.

Lamara's long face was smiling. "He says he doesn't want to be a defense attorney. But he will.”

The conversation grew more animated and I caught one French word. Tribunal. I heard it a second time. I struggled against my own conclusion. Finally Lamara said, "You do understand what they have arranged to do this afternoon, don't you?"

I heard myself answer, "Yes."

"Aren't you frightened?"

Good question, young man, good question. The operative question. But out loud I said, "Is the trial going to be held in this big cave?"

Lamara nodded. Good, I thought. I don't have to think about it yet. I have a technical problem in photography first. The light is bad. Get your lightmeter and take readings up and down in both directions and don't forget what you compute and be sure the judges know you will need to move around during the trial so they don't stop you after it's started and remember to load fresh film in both cameras and . . .

The life of a man is never just a technical problem in photography.

Man and Boy

I could see the words in type.

This one is. This one is a self-confessed mass murderer. You’ve heard his confession with your own ears. It's all very well for a reporter to doubt but nobody is going to talk themselves into a death sentence just to make a propaganda story. Besides, that isn't what you doubt at all.

You doubt the fact of killing. You doubt that the men who have cared for you here and confided In you here and pushed over to you the best of their food are actually going in cold blood to put to death a human being you know, a living human with whom you have identified yourself.

Maybe, but anyhow I don't want to photograph what is happening.

I recalculated the light meter readings on the circular slide rule. There was no use arguing with the numbers. Pictures were possible in this light. They might even be good.

I fitted together the glittering camera parts and the little film cartridges and the big-barreled lenses. One fat lense had been with me for a long time and I was gratified when it locked smoothly into place as if my hands had been steady.

I squatted on my heels leaning against the rock wall on one side of the courtroom. The cave had become that; the officers were taking their places in a semicircle. Lamara was at my elbow. I said, trying to make it sound crisp, "I have two cameras. At the moment of execution I can use only one. I will set the other for you. Will you stand next to me and operate the shutter?"

The young lieutenant looked deeply troubled. "I can't give you my word on it," he shook his head. He gazed gravely down at me. "You see I I get nervous at executions."

There was a long pause. I knew Lamara had said something ludicrous and I ought to smile if only inwardly. But his raw honesty made me tell the truth to myself instead. Now I knew what my real doubt was.

Fine phrases aside how many more days might the boy have lived if I had not shown sympathy for him? Was not the trial and execution being held now because I was there to see it?

The tribunal opened in the hottest hour of the day. A half-moon of five judges were sitting cross-legged. At each end stood an army noncom; the captain had designated one as prosecutor, the other as defense counsel. Between them, the prisoner faced his judges, standing gracefully.

A few yards down the hill behind him were four rebel infantrymen acting as guards. Affixed to their rifle muzzles were three-edged bayonets captured from their enemies.

When the testimony began, the prisoner seemed more at ease than anyone else. In the shaded light from the cave walls, the planes of his face were curved like a child's and there was barely sweat on them. His gestures as he talked were wide and easy, his dirty white robe moving as he swayed. The smooth silvery manacles at his wrists were not tight and they made a tinkling sound when he gestured with his hands. Sometimes you could see the red tattooing on his palms that identified him as having pledged loyalty to the French. When he moved his face to one side of the court or the other, he shifted his weight on his bare brown feet like a dancer.

His name was Banamar, he said, and he had been born in the province of the mountains here. Almost as soon as he could walk, he had herded his family's sheep and goats. When he was old enough to lift a load of rocks of earth, he had become a road laborer. He was paid enough each day to buy six loaves of bread, he remembered.

One day, Banamar related, a man in the uniform of the French army asked him if he would like to come away from the road and into the mountains with three of his friends who, too, worked on the road. The soldier promised them they would always have enough to eat.

The Algerians went with him. Life in the mountains was not hard at first and they were told that if they pleased their French noncom bosses, they would have a chance to earn a great deal of money four thousand francs. But first their allegiance must be proven. They were to go back into the villages and talk with the people, saying they were looking for lost camels. They were to learn where the rebel army was operating, where the migrant tribes grazed their herds and which villages and tribes were helping the rebel saboteurs.

This work was easy, and Banarnar said he always found out quickly whatever the French wanted to know. Then they would seat him in an armored truck at the head of the assault against the pro-rebel communities he had identified. The French would surround the village or the shepherds* tents, set fire to the roofs of their dwellings and shoot the people as they fled, Banamar explained, making a circle with his manacled hands.

Hamitou had grown bored. He was familiar with these tactics and he moved his shoulders impatiently as if their recital were unnecessary now. "Yes, yes, go on/' he ordered.

Soon, the prisoner related, he had a chance to earn the four thousand francs. When the firing on one village was done, a noncom told him that in two of the huts there were still some old men and women and children left alive.

"Banamar, go in and kill them with your knife," the sergeant said.

Banamar told the court he did not do anything at first; he only stood very still.

The French soldier leveled his submachine gun at him.

So Banamar did as he had been told. It was not very different from killing sheep, he explained. He did it the same way. First the old man whose hands he tied as you tie the front legs of a sheep. Then two women. Only one of them screamed. And finally a baby.

When he came back to the armored truck, he learned that his three friends had done as he had done. The French non-com said they had each earned their money. They did not get all of it. Most, they were told, was sent to their parents and some was used to pay for the food they had been eating

in the mountains.

The next killings were easier. Banamar said he did not remember them very clearly. The noncom had warned him each time, "If you do not do as we tell you, we will deliver you to your own people.'

Once Banamar said he did not kill a young girl whom he found. He brought her to the sergeant. The noncom was pleased. But after she had been five days a prisoner, Banamar said he had to kill her after all.

Almost two years went by and it was always the same- find the rebels, report back to the soldiers, lead in the armored truck, kill the survivors of the attack.

A week before his trial, Banamar was set down by a U.S.- built helicopter on the edge of a tribal village about fifty miles from the cave of the courtroom. Perhaps the pilot was careless of his security; somehow the people of the tribe saw the dust of his landing. Their police, acting with the authority of the FLN, quickly took Banamar into custody. They arrested him even before they saw his tattooing because he did not have the identity papers needed for a person who belonged in their sector.

Banamar had not lied about himself to them. He told them he had been a spy and butcher for the French because he was sure he would be killed immediately otherwise. The police had walked him at gunpoint to the Scorpion Battalion headquarters at once.

He had never changed his story. It had been no different this morning.

Finally the judges had heard it all. Each of them questioned him, and the soldier who was acting in Banamar's defense made a plea based on his youth. This took almost an hour and the junior officers sitting at the edge of the half-moon were looking at their watches before it was over.

Only the president of the court, Colonel Hamitou, showed emotion. And only once. Then, with deep contempt, he leaned over his knees to the prisoner. His sheer posture was an act of assault. "If I were told to kill my own brothers, as you were, I would be able to find something else to do except what I was told." He added without any inflection, "Do you ask the mercy of the court?"

Banamar had not flinched. His brown face reflected the light from the cave walls and seemed translucent in it. "I ask only the mercy of Allah. He knows I could not stop

myself from killing."

The four guards led the prisoner down the rock-strewn hill.

Training in a Mine Setting

"The court is open for deliberation," Hamitou intoned, almost wearily. He and Ben Chafa spoke first among themselves, then turned to the men at their sides. In less than two minutes, Hamitou called for a vote. Only one vote, "Signify for the death sentence," he said.

All five hands, his own in the center, were raised.

A few hundred yards down the valley there was a sloping pebbled field dotted with clumps of alfalfa. In a quarter of an hour, a company of infantry was assembled, formed into three sides of a square, the open end facing the lowering sun. Volunteers for the firing squad came from among those men whose wives and children Banamar could possibly have killed.

Hamitou designated a low jutting stone as the place where the prisoner was to stand. The squad was called forward and twice rehearsed with their rifles as if they had not done this before. Hamitou finished, "You will fire on the count of three."

The prisoner was led forward to the spot where he would die. He faced the East and the firing squad, erect and grave. Captain Ben Chafa was at my elbow. "Please be sure your pictures show that the body was removed without being mutilated." I nodded weakly.

Two days later, in front of a white-balconied Madrid hotel, I was being bade farewell from the FLN by two impeccably groomed young men in business suits who looked as if they might have been guides from a tourist agency. They told me I was not a kidnapee any longer; I could now phone America if I wished to report my safe return. They handed me the paper-and-string-wrapped package containing the hundred dozen photographs I'd made of their forces, which they had been guarding along with me. Their final words were the same benediction I'd received from Abdel Kader, bon courage.

As the men melted into the strolling crowd, I felt again the sense of unreality I had known during my first days of security after my time in Hungary. The men had been the couriers on the final lap of my journey and I, in the veil and robe of an Arab woman, had met them first in their djalabbas on the far side of the Mediterranean. They would now go back there to fight on, and I would again sleep in a bed, shower under hot water, eat all the food my stomach would hold and wonder why, in a world of order and plenty, it was so hard to tell of violence and want. Strangest of all in that moment, was the fact that to try to do this was my profession.

To cross the chasm between them, to move from Algeria to America in 1957, took me only a few days. But it was months before my mind and heart had made the same crossing. Finally four years had passed and a dozen other American journalists had made the same kind of visit to the Algerian rebels as I had. Joseph Kraft of The Saturday Evening Post had written a prize winning book about it. Frank Reams of CBS News had produced an award winning documentary film. All of us told the same story.