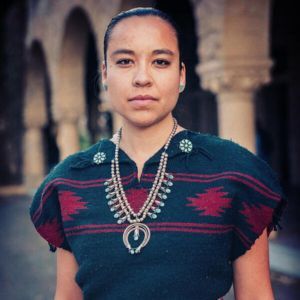

Lyla June Johnston

Lyla June Johnston is an Indigenous musician, scholar, and community organizer of Diné (Navajo), Tsétsêhéstâhese (Cheyenne), and European lineages. Her work centers on healing intergenerational trauma, advocating for Indigenous rights, and promoting ecological regeneration.

Raised in Taos, New Mexico, Lyla June was immersed in a worldview where music and song are integral to healing and spiritual practice. In Diné culture, the term "Hataalii" means both "singer" and "doctor," reflecting the deep connection between song and healing. This foundation inspired her to pursue higher education, earning degrees from Stanford University and the University of New Mexico, where she focused on Human Ecology and Indigenous Pedagogy.

Her doctoral research, titled Architects of Abundance: Indigenous Regenerative Food and Land Management Systems and the Excavation of Hidden History, explores how pre-colonial Indigenous Nations shaped large regions of Turtle Island (the Americas) to produce abundant food systems for both humans and non-humans.

Beyond academia, Lyla June is a passionate advocate for Indigenous sovereignty and ecological justice. She co-founded the Taos Peace and Reconciliation Council to address intergenerational trauma and ethnic division in northern New Mexico. She also organized the Black Hills Unity Concert, bringing together Native and non-Native musicians to support the return of guardianship of the Black Hills to the Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota nations.

Through her music, poetry, and public speaking, Lyla June inspires audiences worldwide to reconnect with the Earth, embrace Indigenous knowledge, and foster compassion and kinship across cultures. Her work exemplifies a commitment to healing, justice, and ecological stewardship, offering a model for integrating compassion and love into both personal and collective action.

Dawn

It is dawn.

The sun is conquering the sky and my grandmother and I

are heaving prayers at the horizon.

“Show me something unbeautiful,” she says,

“and I will show you the veil over your eyes and take it away.

And you will see hozho all around you, inside of you.”

This morning she is teaching me the meaning of HOZHO.

There is no direct translation from Diné Bizaad,

the Navajo language, into English

but every living being knows what hozho means.

Hozho is every drop of rain,

every eyelash,

every leaf on every tree,

every feather on the bluebird’s wing.

Hozho is undeniable beauty.

Hozho is in every breath that we give to the trees.

And in every breath they give to us in return.

Hozho is reciprocity.

My grandmother knows the meaning of hozho well.

For she speaks a language that grew out of the desert floor

like red sandstone monoliths that rise like arms out of the earth

praising creation for all its brilliance.

Hozho is remembering that you are a part of this brilliance.

It is finally accepting that, yes, you are a sacred song that

brings the Diyin Dine’é, the gods, to their knees

in an almost unbearable ecstasy.

Hozho is re-membering your own beauty.

My grandmother knows hozho well

For she speaks the language of a Lukachukai snowstorm

the sound of hooves hitting the earth on birthdays.

For my grandmother is a midwife and she is fluent in the

language of suffering mothers

of joyful mothers

of handing glowing newborns to their creator.

Hozho is not something you can experience on your own,

the eagles tell us as they lock talons in the stratosphere

and fall to the earth as one.

Hozho is interbeauty.

My grandmother knows hozho well

for she speaks the language of the male rain

that shoots lightning boys through the sky,

pummels the green corn children,

and huddles the horses against cliff sides in the afternoon.

She also speaks the language of the female rain

that sends the scent of dust and sage into our homes

and shoots rainbows out of and into the earth.

The Diné know what hozho means!

And you know what hozho means!

And deep down we know what hozho is not.

Like the days you walk in sadness.

The days you live for money.

The days you live for fame.

The days you live for tomorrow.

Like the day the spaniards climbed down from their horses

and asked us if they could buy the mountains.

We knew this was not hozho.

But we knew we could make it hozho once again.

So we took their swords and their silver coins

and melted them

with fire and buffalo hide bellows

and reshaped them into squash blossom jewelry pieces

and strung it around their necks.

Took the helmets straight off their heads

and turned it into fearless beauty.

Hozho is the healing of broken bones.

Hozho is the prayer that carried us

through genocide and disease,

It is the prayer that will carry us through global warming

and through this global fear that has set our hearts on fire.

This morning my grandmother is teaching me

that the easiest (and most elegant) way to defeat an army of hatred,

is to sing it beautiful songs

until it falls to its knees and surrenders.

It will do this, she says, because it has finally

found a sweeter fire than revenge.

It has found heaven.

It has found HOZHO.

This morning my grandmother is saying

to the colors of the sky at dawn:

hózhǫ́náházdlíí’

hózhǫ́náházdiíí’

hózhǫ́náházdlíí’

beauty is restored again…

It is dawn, my friends.

Wake up.

The night is over.

Listen Lyla June read her poem.